This post is part of a series of stories looking back at the top naval news from 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic affected almost everything the Navy did in 2020, from the way the service deploys forces, to the way its contractors built ships and weapons, to the way sailors and officers were educated and trained.

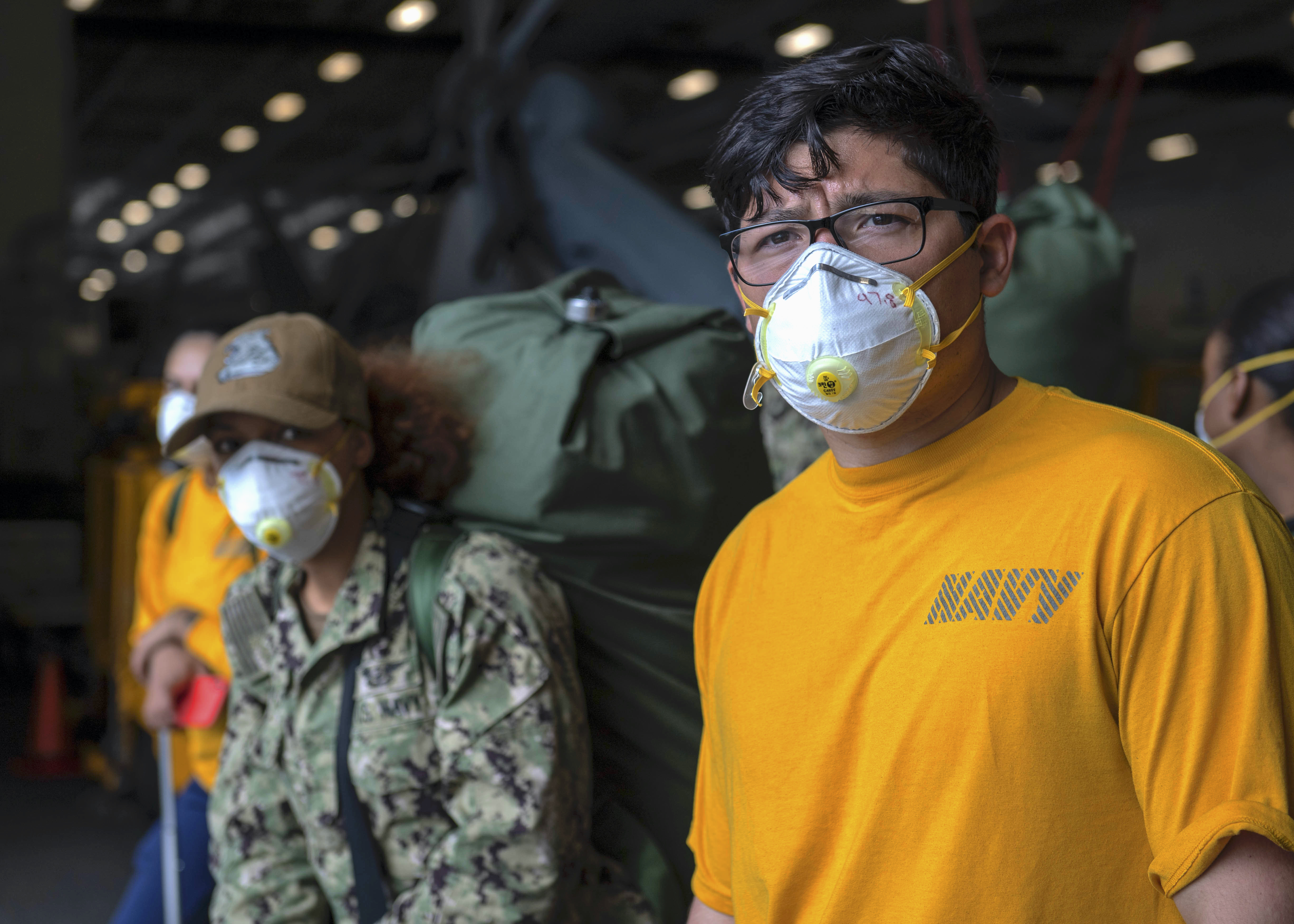

The outbreak on USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) gained the most attention due to the scale of the outbreak – more than 1,200 personnel were infected – and the political fallout – the ship’s captain was fired by then-Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Modly, who then, in turn, was fired for his handling of the outbreak. Though garnering less attention, dozens of other ships and bases saw cases, too, which they had to quickly quell with new and evolving Navy protocol before they spread out of control.

Since February – when Navy personnel stationed in Italy first had to worry about growing infection rates and looming lockdowns – 29,060 Navy sailors, dependents, civilians and contractors have contracted the disease. Two sailors have died, as have 26 civilians, 12 contractors and one dependent.

Theodore Roosevelt Outbreak

The Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group deployed Jan. 17, when the virus was still largely a problem for China and surrounding countries. The aircraft carrier implemented some mitigation steps such as bleaching hard surfaces twice a day, but the risk was considered so minimal that a port call to Vietnam was made March 5, with U.S. Pacific Fleet leadership flying in for a 400-person reception to mark the carrier’s historic visit to Da Nang. Thirty reporters were brought out to the carrier for tours.

As the port call was ending, 39 sailors from the carrier were put into quarantine after it was discovered that two British travelers staying at their hotel were infected, but by March 14 they had all tested negative for the disease and were let out of quarantine. Carrier onboard delivery, or COD, flights continued to and from the ship throughout much of March.

On March 24, the first three sailors were diagnosed with COVID-19. Navy leadership denied the outbreak was tied to the port call in Vietnam. The three sick sailors were flown off the ship to quarantine on Guam.

Two days later, the carrier pulled into Guam. At the time, the Navy said they had found “several” more cases on the ship, though by April 1 that rose to 93 positive cases, by April 12 it was 585 positive cases, and by April 14 it was 950 sailors. In total, more than 1,200 sailors, or about a quarter of those in the ship’s crew and air wing, contracted the disease.

Following a March 30 memo from then-TR Commanding Officer Capt. Brett Crozier, on March 31 PACFLT Commander Adm. John Aquilino said the Navy was looking for government housing and hotel rooms for sailors on TR to quarantine ashore.

Though most of the sick sailors were able to quarantine in single-person rooms and wait out the illness, one was found unresponsive in his room during the twice-daily medical checks. Aviation Ordnanceman Chief Petty Officer Charles Robert Thacker Jr., 41, died April 13 in U.S. Naval Hospital Guam from complications from COVID-19.

After 55 days in Guam battling the outbreak, the carrier returned to sea on May 20 with about half its crew to begin workups ahead of resuming the deployment. A minimal crew was used during this event, as many were still completing their quarantines and awaiting two consecutive negative COVID tests. On June 3 the carrier picked up the air wing and much of the rest of the crew. The carrier rejoined its strike group and remained on deployment in the Pacific until July 9.

Leadership Fallout

Even as Theodore Roosevelt was tied to the pier in Guam, the ripples from the outbreak were being felt at the Pentagon.

After Crozier’s March 30 memo was leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle, reactions were mixed: some were horrified that the sailors on TR had to face the deadly outbreak with so little help from their chain of command, while others were shocked that Crozier went around that chain of command and blasted out his plea for more rapid assistance even as plans were already in the works.

Modly fired Crozier on April 2, saying he “demonstrated extremely poor judgment in the middle of a crisis.” In the immediate aftermath, President Donald Trump and then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper expressed support for Modly’s decision.

However, Modly flew to Guam and spoke to the sailors on April 6, telling them in a mix of prepared remarks and off-the-cuff comments – which were recorded and leaked to the press – that Crozier may have committed a “serious violation of the Uniformed Code of Military Justice” and was not fit to command a carrier. After the speech audio was leaked, Modly tried to apologize, but the damage was done: lawmakers quickly began calling for his resignation. Modly resigned the next day.

A preliminary investigation by Navy uniformed leadership into the handling of the outbreak on the carrier was set to end April 6, but its release dragged, with word leaking in late April that Navy leadership wanted to reinstate Crozier as skipper of the carrier. After Esper suggested there may be more questions that needed to be answered, a longer investigation spanned until late May, and ultimately on June 19 the Navy announced Crozier would not be reinstated as captain of TR.

USS Kidd, Other Ships

Theodore Roosevelt was the ship hit hardest by COVID, but it was not hit first.

By mid-March, sailors assigned to San Diego-based ships USS Boxer (LHD-4), USS Ralph Johnson (DDG-114) and USS Coronado (LCS-4) had already tested positive for COVID-19, as had four Naval Special Warfare sailors training at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor. On March 24, the day the Navy announced three TR sailors had been diagnosed with COVID-19, 54 other sailors had already been diagnosed with the disease elsewhere in the fleet. Around that time, PACFLT ceased announcing which ships and units were affected by COVID, calling it “a matter of operational security.”

Still, the Navy couldn’t hide another outbreak on a deployed ship: USS Kidd (DDG-100). The destroyer had been serving in the Theodore Roosevelt CSG, but the sailors were not involved in the Vietnam port call or in contact with the ship’s crew or air wing. In April, Kidd peeled away from the CSG – with the carrier in port in Guam – to serve in U.S. Southern Command as part of a counter-drug effort. On April 24, the Navy confirmed 18 sailors on the ship had tested positive, even though a month had passed since the ship made its last port call in Hawaii.

Amphibious assault ship USS Makin Island (LHD-8) was ordered to rendezvous with Kidd in the Eastern Pacific to lend its fleet surgical team, intensive care unit, ventilators and testing capability if the Navy needed to treat the outbreak at sea. After 15 sailors were moved to Makin Island for treatment and two more flown ashore for care, the Navy ordered Kidd to return to San Diego.

American sailors weren’t the only ones facing the disease: an April outbreak on French aircraft carrier FS Charles de Gaulle (R91) quickly numbered in the hundreds, with ultimately about two thirds of the crew – 1,046 sailors out of 1,760 – plus a few dozen on other ships assigned to the carrier strike group contracting COVID-19. In October, more than 30 members of the crew of the U.K. Royal Navy ballistic-missile submarine HMS Vigilant (S30) tested positive for COVID-19 following a port visit to Navy Submarine Base Kings Bay in Georgia. In early October, most of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were in quarantine after Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard Adm. Charles Ray tested positive for the disease following a meeting with the Joint Chiefs.

Safety Protocols

By the time a small group of sailors on USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) tested positive for COVID-19 in early September, the Navy had refined its protocols well enough to avoid a major outbreak.

Starting with the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group workups and deployment in April, a ship’s crew had to quarantine for 14 days before heading to sea, and the squadrons conducted their quarantine at their home stations before flying out to the carrier. Because of the need to quarantine for two weeks ahead of going to sea, the Navy changed up the schedule for pre-deployment training and certification. Previously the ships would go to sea for advanced phase training such as the Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training, come home, regather for a Composite Training Unit Exercise (COMPTUEX) certification exercise, go home to bid their families farewell, and then deploy. Now, with the threat of a COVID infection rising every time the sailors left their bubble and went home, the Navy decided to consolidate all the activities, with the ships heading out to sea for training and certification and then flowing right into their deployment. Creating a COVID-free bubble, plus buying enough test kits for ships to use prior to and during deployments as well as implementing social distancing and mask-wearing policies, was thought to create safe enough conditions for the Navy to continue deploying as needed around the globe during 2020.

Though safer for the sailors deploying, the Navy has broken several records this year for most at-sea time, since the sailors have been at sea with no breaks for not only the seven-month deployment but also all the training that led up to deploying.

As the Navy worked its way through figuring out how to get its first strike group, the Nimitz CSG, out the door without any COVID cases, the service decided it needed to have a COVID-free carrier ready in case of emergency. As a result, the Harry S. Truman CSG was ordered to stay off the coast of Virginia upon the completion of its deployment to the Middle East. Until Nimitz CSG was certified and ready for national tasking, the Navy couldn’t take any chances with Truman CSG sailors coming home, getting sick, and then being asked to get back to sea for an emergency assignment. That at-sea loitering lasted from about April 13 to June 16.

Adding to the burden of longer at-sea times was the inability to safely set up port calls during deployments. In the early days of the pandemic, the Navy in late February called for a 14-day period between port calls in U.S. 7th Fleet – a “prudent” step “to protect our ports and prevent any particular spread to our allies and partners and, obviously, protect our forces,” the Navy said – but that turned into an all-out ban on port calls by late March. A handful of “safe haven” ports were created, including the first one in Guam in June, so sailors could get off their ships and have access to cell phone reception without coming into contact with anyone outside their crewmates. However, not all ships had access to safe haven ports, leading to some difficult deployments this year: USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), for example, was at sea for 161 consecutive days during its deployment.

Other major changes for the Navy revolved around moving new recruits around for basic training and follow-on job training, as well as allowing for permanent change of station moves around the globe.

What started out as blanket bans on movement, liberty and other opportunities for sailors to be exposed to the virus became more nuanced as the Navy and the world learned more about COVID-19. On March 15 Esper announced a stop-movement order initially set to last two months, though in May it was extended to late June. As it became clear that the military would have to learn to live with COVID-19 for at least another year, the policies restricting movement became more conditions-based, allowing local base commanders to play a greater role in determining when it was safe for them to “reopen” for personnel movements again, for example. After a short halt in bringing new recruits to basic training, they were allowed into training after completing a 14-day restriction of movement (ROM) quarantine ahead of time – for a time, that ROM was conducted in a closed water park in Illinois due to lack of single-person rooms at the recruit station – and once in basic training they were kept in a “bubble” that saw them through their initial military occupational specialty training and into their first assignments, having no contact with the outside world and no leave time until they had successfully completed training.

Hospital Ship Responses

When New York City was facing a nightmarish situation early in the pandemic, and then soon after Los Angeles-area hospitals were overwhelmed too, the idea of deploying Navy hospital ships to alleviate the stress on overflowing hospitals was exciting to many.

By March 17 USNS Mercy (T-AH-19) and USNS Comfort (T-AH-20) were beginning to get activated, and the next day Trump said Comfort would deploy to New York City. Mercy was originally expected to go to Seattle, whose suburbs had the very first outbreaks in the United States, but on March 23 the ship left San Diego for a short trip up to Los Angeles, which was deemed more likely to have patient need surpassing hospital capacity. Comfort left Norfolk, Va., for New York on March 28.

Though expectations were high, the ships did not contribute as much as expected: the plan was to bring non-COVID patients to the ships, allowing the staffs there to focus on trauma care and heart attacks, while the city hospitals with better ventilation and isolation capabilities focused on the highly infectious disease. Instead, the screening process proved too cumbersome to bring in patients in great numbers, and patients brought to the ships for things like broken bones turned out to have COVID too.

By late April, Comfort left New York City having treated 182 patients, and Mercy left Los Angeles after treating 77 patients.