This post is part of a series of review stories looking back at the top naval news from 2019.

2019 started with a surprise in the Navy budget request: the service needed to buy and test unmanned surface vehicles immediately to reach its ultimate goals for the surface force, and it was willing to sacrifice almost anything – including sidelining an aircraft carrier – to free up the funds to do so.

The year continued with a contract award for the first carrier-based unmanned aircraft, troubles with the Ford-class aircraft carrier program, a focus on getting the frigate program contract awarded on time, and a lengthy negotiation on the Block V Virginia-class attack submarine contract award amid the beginnings of Columbia-class sub construction.

Unmanned Ships

The move to pursue unmanned surface vessels as a major part of the future fleet was perhaps the defining aspect of 2019 Navy acquisition.

When the Fiscal Year 2020 budget request came out, the Navy asked for money for a 10-ship “Ghost Fleet” of large unmanned surface vessels over the next five years – two USVs a year for a total cost of $2.7 billion, or about the cost of one and a half destroyers.

Though the effort caught the media, the public and lawmakers off guard, the Navy has claimed it has a strong technical understanding of USVs and what it will take to successfully develop and integrate a large and medium USV into the fleet. The timelines for both LUSV and MUSV programs were bumped up, in a nod to the urgency with which the Navy wants to begin testing and fielding. Few had heard of the LUSV before the March budget request rollout, yet by August the Navy had a request for proposals for its corvette-sized LUSV out to industry, following the July RFP for the MUSV program.

To begin learning what kinds of payloads might be useful and what tactics might best leverage USVs, the Navy stood up Surface Development Squadron 1 to conduct “aggressive experimentation” with more unique surface assets – the three Zumwalt-class destroyers that the Navy has built but not finessed what their role in the fleet; the LUSV and MUSV; and potentially eventually the Littoral Combat Ship. This fall the SURFDEVRON began taking control of the first Sea Hunter MUSV, with a second MUSV and two Pentagon-built LUSVs to follow in the next two years.

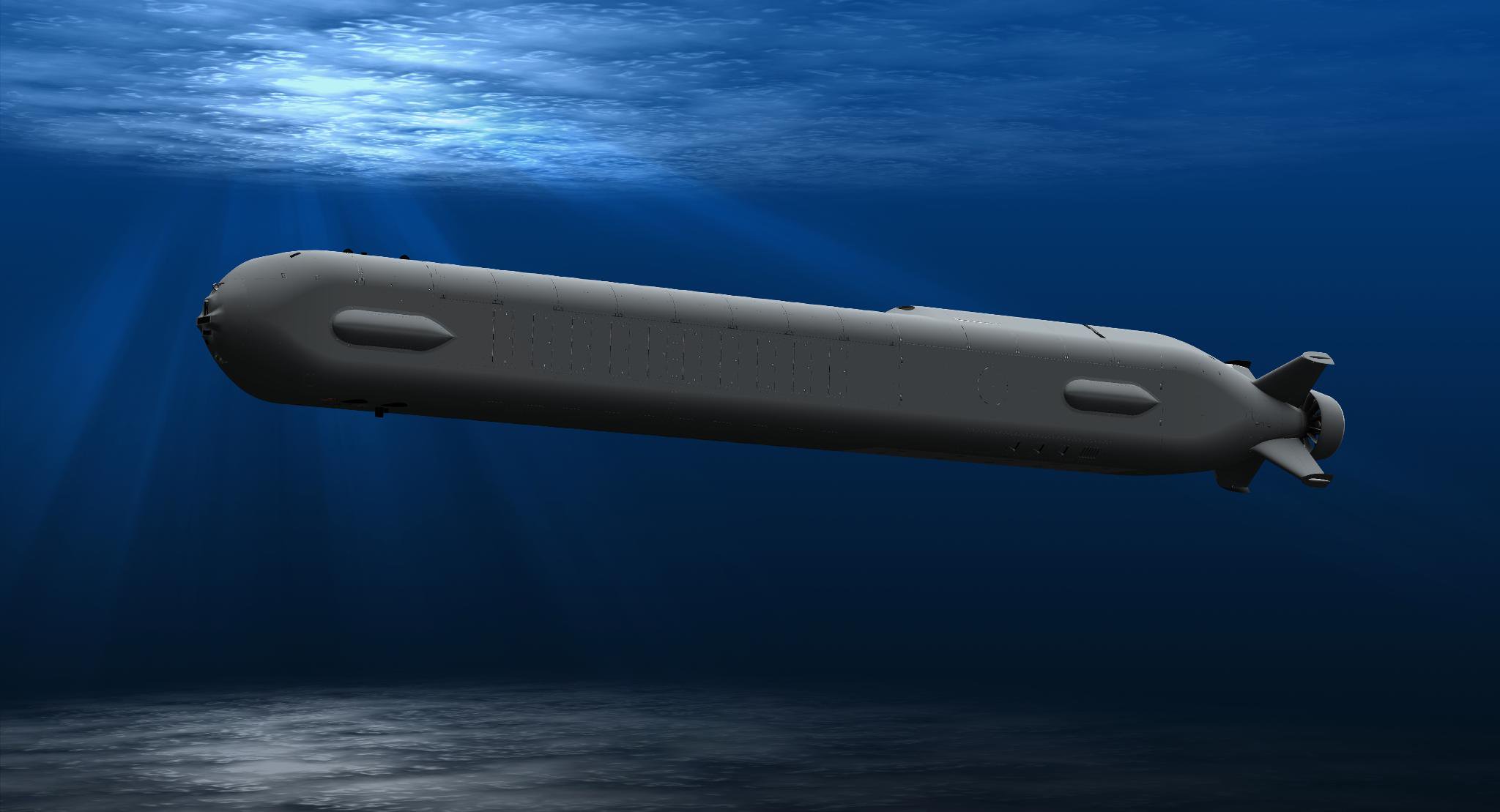

On the unmanned undersea side, the Navy in February awarded Boeing a $43-million contract for four Orca Extra Large Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (XLUUV). Boeing based its winning design on its Echo Voyager unmanned diesel-electric submersible, a 51-foot-long submersible that can operate autonomously while sailing up to 6,500 nautical miles without being connected to a manned mother ship, according to the Navy. Eventually, the Navy could use the Orca XLUUV for mine countermeasures, anti-submarine warfare, anti-surface warfare, electronic warfare and strike missions.

Aircraft Carriers

The Navy was willing to sacrifice carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) in its bid to free up money for USVs but Congress pushed back and demanded the Navy keep the carrier fleet intact due to its importance to global operations. Carriers proved to be a headache in 2019 – with the weapons elevators on USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) causing trouble for leaders, all the way up to the Secretary of the Navy, and with the maintenance of today’s carriers being a challenge to fund and execute.

Eight days into the year, Richard V. Spencer told a think tank audience about his recent conversation with President Trump about Ford and its continuing problems with the advanced weapons elevators.

“I asked him to stick his hand out; he stuck his hand out. I said, let’s do this like corporate America. I shook his hand and said, the elevators will be ready to go when she pulls out or you can fire me,” Spencer said, referring to Ford coming out of its post-shakedown availability that at the time was scheduled to end in July.

The ship didn’t come out of PSA in July, and the elevators weren’t done when it eventually did get back out to sea.

Additional experts were brought in to try to help get the elevators up and running and certified. The challenge is each elevator is unique and has to navigate the ship and seal its doors in a different way than each of its 10 fellow weapons elevators. The estimated completion date slipped several times throughout the year. Ultimately the Navy got Ford out to sea and was happy with the status of most of its technologies, and the potential the ship has for future operations with high sortie rates, but critics remain. News the ship may not deploy until 2024 due to remaining testing, including full ship shock trials, as well as news that the ship won’t be able to accommodate the fifth-generation F-35C Joint Strike Fighter on that first deployment, only added fuel to the criticism of the Ford-class program.

Still, after a New Years Eve 2018 announcement that a two-carrier deal was coming, the Navy on Jan. 31 inked a deal with Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding to buy two carriers in a single contract, with the potential to save more than $4 billion across the two ships.

Second-in-class John F. Kennedy (CVN-79) was christened in December, and the Navy eyed work to upgrade two dry docks – one on each coast – to support Ford-class carriers, in a move that suggests Ford will remain in Norfolk, Va., and Kennedy will head to the West Coast once it joins the fleet.

Frigate Competition

Talk of the frigate competition in Fiscal Year 2020 will be limited due to the ongoing competition, but early in 2019 the bidders and program office were chatty about their hopes and needs in this competition for a small surface combatant to follow after the Littoral Combat Ship line ends.

In March the Navy released the draft request for proposals for the FFG(X) program, with the final RFP coming in June. The documents laid out an acquisition plan for the first 10 ships that would spend about $1.3 billion and 72 months building the lead ship, with the cost and construction time going down for subsequent hulls.

Spanish shipbuilder Navantia spent the year showing off its design at conferences and through the inclusion of ESPS Mendez Nunez (F-104) serving in the Abraham Lincoln Strike Group in 2019. BAE Systems opted not to enter the competition with the British Type 26 frigate design, and Lockheed Martin pulled its Freedom-class LCS design from the competition.

Large Surface Combatants

Though the large surface combatants are meant to be less numerous than the small combatants in the future fleet design, the large combatants generated much more talk and consternation than their smaller counterparts in 2019.

Talks between the Navy and industry kicked off at the beginning of the year, with the Navy knowing it needed a large combatant that could carry big missiles and radars but needed the stealth capability of the Zumwalt-class DDG. Much of the rest of the design is being left up to a team of engineers, budget officers, fleet representatives, industry and researchers who can work together to figure out the best way to design and field a new large combatant.

Early on it sounded as if no existing ship design could meet all of the Navy’s needs, the service pulled back this summer, stating it wanted revolutionary advances in capability through new weapons and sensors but it was likely to stick to tried and true hull designs and systems. The timeline also slipped from an aggressive 2023 start to 2025 timeframe to 2026 or later, suggesting the service didn’t have a clear path forward to get the new capability it needed while leveraging known and less risky technologies and designs.

Meanwhile, Arleigh Burke-class Flight III DDG production remained “on track” this year – a good thing, if the production line gets extended while the Navy figures out what it wants from a future surface combatant. The Zumwalt-class continued on with combat systems integration and testing on the lead ship of the class.

To support these combatants, Lockheed Martin announced the Aegis Combat System Baseline 10 capability associated with the Flight III design could be backfit onto existing ships that have older radars, and the AN/SPY-6 radar built for the Flight III ships completed its final round of developmental testing.

Submarines

Though submarines – and the Columbia SSBN in particular – are meant to be top acquisition priorities, they generated less acquisition news in 2019 than other parts of the fleet.

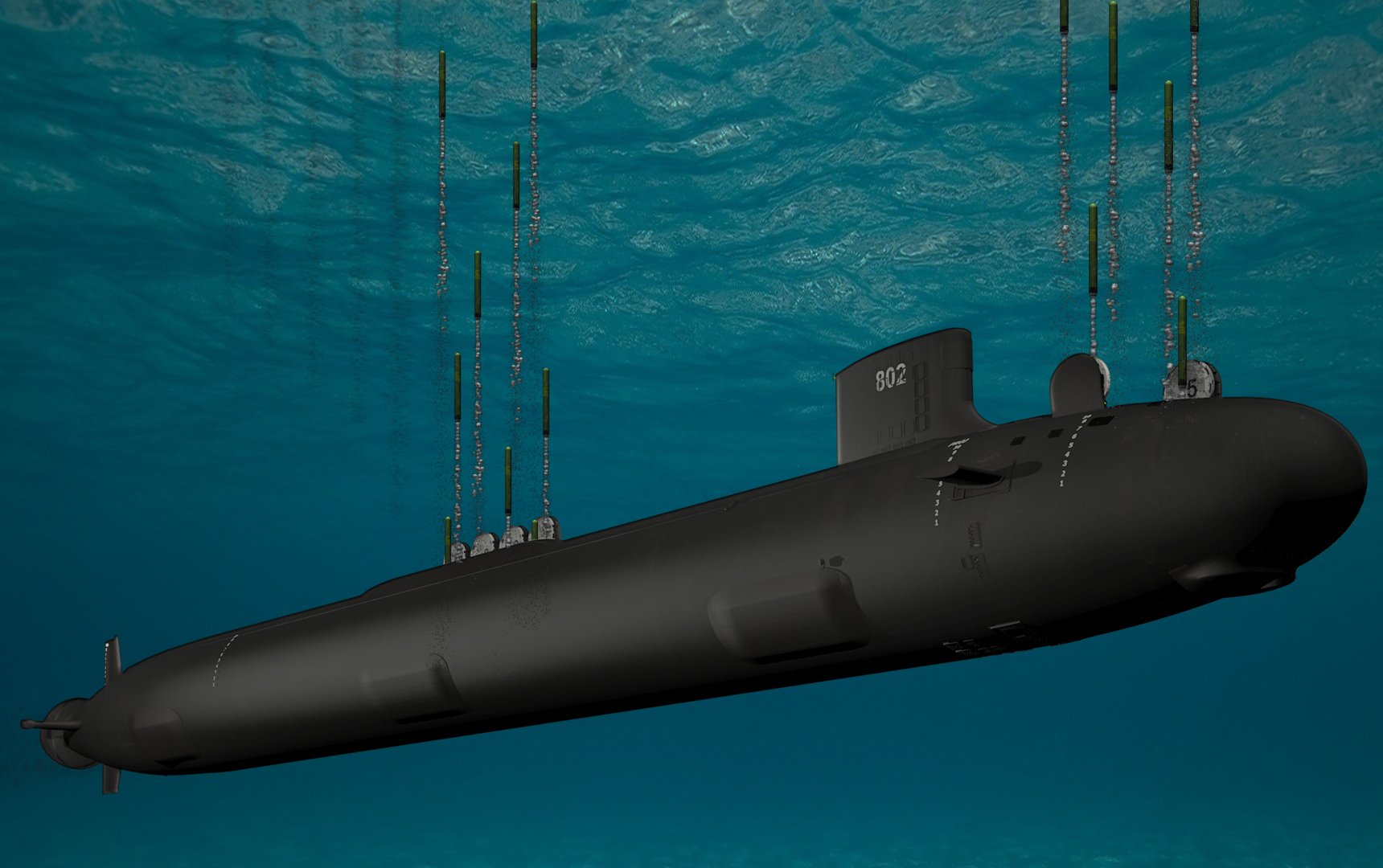

The Virginia-class SSN program spent the bulk of the year with the Navy and industry team in protracted contract negotiations. The Navy anticipated awarding a contract in April, and an agreement was finally reached in December for nine subs with an option for a 10th, compared to original plans to buy 10 with as many as three options for additional boats to meet high operational demands. The deal sought to protect the industrial base, shield the Columbia SSBN program from adverse effects, and keep costs down.

On the Columbia side, the Navy created a new program executive office to oversee just this one top priority, whereas the future SSBNs were formerly housed under the PEO for Submarines.

Though prime contractor General Dynamics Electric Boat boasted a highly mature design for the program, saying it would be the most complete ever for the Navy, the program still faces great challenges due to the fragility of the submarine industrial base that’s being asked to do a lot right now: Columbia, Virginia, and a new Virginia Payload Module segment that requires new facilities and additional labor to build. Electric Boat and major subcontractor Newport News Shipbuilding have already made extensive facilities upgrades to accommodate all the new work. Still, the Government Accountability Office has warned that the program is at risk of delays due to new and unproven technology.

Looking ahead, the Navy is already planning for the next block of attack subs that will focus on special operations and incorporating unmanned systems.

The Future of the Carrier Air Wing

The service declared initial operational capability (IOC) on its F-35C Joint Strike Fighter in February, after Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 147 conducted aircraft carrier qualifications aboard USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) and received its safe-for-flight operations certification in December 2018 and then proved the squadron was capable of independently operating and maintaining its new jets.

VFA-147 has been training on its own and preparing to join and deploy with an air wing likely in 2021. Following IOC, the Joint Strike Fighter Wing is balancing its focus between getting the “Argonauts” ready for this first deployment while also transitioning the next units over to the F-35C. The second unit to become operational and prepare for a deployment is a Marine Corps F-35C unit, Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 314.

On the unmanned side, after an August 2018 contract award to Boeing for the MQ-25A Stingray unmanned tanker program, the Navy began preparing for a quick turnaround to first flight. That flight happened in September and was described as “boring,” which was exactly the non-eventful test event the Navy had hoped for.

For rotary-wing unmanned aerial vehicles, the Navy declared IOC for the MQ-8C Fire Scout.

The Navy also awarded Sikorsky a contract for six presidential helicopters after reaching a handshake agreement the month before,

Future Weapons

The Navy is moving quickly towards future weapons that have a much lower cost per engagement and can be effective against drones and other emerging threats to surface ships and other Navy assets.

USNI News reported in January that the Navy had previously fired 20 hypervelocity projectiles (HVP) from a standard Mk 45 5-inch deck gun from USS Dewey (DDG-105), testing a new projectile that could be added to most U.S. surface combatants with little integration. The Navy had a particular eye to incorporating this weapon onto the Zumwalt destroyers, as their previous land-attack weapon was nixed and the three-ship class was left without a plan for its newly reassigned blue water mission.

The service also moved forward on laser guns, planning a major 2021 test on a destroyer, with smaller steps planned for the nearer term such as on-ship integration of a high-end laser and a lower-powered laser dazzler this year to begin learning how the system functions aboard a working ship and to begin letting the crew understand its utility.

With the Navy and Pentagon clearly focused on hypersonics and directed energy, the industry has adjusted accordingly. Lockheed Martin has been investing internally for years in hypersonics and now has $2.5 billion in military contracts, the company announced this year. Reading the tea leaves for the future of warfare and the U.S.’s need to protect itself from emerging weapons as well, Raytheon and United Technologies pitched their proposed merger this year as a perfect opportunity to pair their expertise and cash resources towards researching hypersonics and counter-hypersonics.