This post has been updated to include additional information from a Navy budget briefing.

THE PENTAGON – The Pentagon requested a Fiscal Year 2020 budget that advocates changes in the way the Navy does business – pushing for lethal but “attritable” unmanned systems, artificial intelligence and hypersonics to give the Navy and Marine Corps an edge against high-end adversaries.

The $205.6-billion Department of Navy budget request trims ships and aircraft that do not meet that new style of fighting, planning for the early retirement of an aircraft carrier and slowing procurement profiles for amphibious ships, F-35 Joint Strike Fighters and F/A-18E-F Super Hornets. While the Pentagon is clear on what it wants to cut, the budget sheds little light on the unproven new systems it wants to add.

“The hard choices required to achieve this balance include trade-offs in legacy force structure allowing the trade space to accelerate investments in future force capabilities for the future fight,” according to a Navy budget document.

“The Department is developing and fielding new capabilities in the areas of unmanned vehicles, directed energy, artificial intelligence, hypersonics and other advanced weapons technology.”

The budget request outlines a path to reach a 314-ship fleet by 2024 –smaller than last year’s plan to reach 326 ships by 2023, in part due to a plan to cancel a cruiser modernization and life extension effort.

Ship Procurement

The Navy is requesting to spend $23.8 billion on shipbuilding and conversion, including $22.2 billion to buy 12 new ships.

Under this proposal, the Navy would buy:

- three Virginia-class attack submarines and three Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers – one more each than is required under the multiyear contracts for each program, showing support for these platforms’ role in the future fleet. All three SSNs will be the Block V design with acoustic superiority upgrades, and two of the three will include the Virginia Payload Module section that adds 28 Tomahawk cruise missile launch tubes.

- one Ford-class aircraft carrier, CVN-81. This carrier was purchased under a two-carrier contract signed on Jan. 31, and buying it this year represents a three-year acceleration of the ship compared to previous plans to purchase it in 2023. The service will spend $2.35 billion in FY 2020 on aircraft carrier procurement, but given the way the Navy splits the cost of its carriers over multiple years, it is unclear how much of this cost covers which hulls. The Navy has not yet released details on the funding profile of the two carriers over future years and whether buying the two carriers in one contract will have much of an effect on per-year costs.

- the lead ship in the new guided-missile frigate (FFG(X)) program, set to cost $1.28 billion.

- two John Lewis-class oilers and two T-ATS towing, rescue and salvage ships.

The shipbuilding account also covers two large unmanned surface vehicles, something the Navy has not yet done much work on to decide on requirements, capabilities or cost. The budget includes $400 million for these unmanned vessels in the research and development portion of the budget.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Budget Rear Adm. Randy Crites told reporters during a budget briefing that the Large USV would be 200 to 300 feet in length and weigh about 2,000 tons, but not much else was known yet about the hull form. He said these first vessels would be test articles to help the Navy begin to understand what kind of unmanned system it needs for a future fight that emphasizes distributed lethality and unmanned or optionally manned vessels.

“We’ve got to get through the details of concept of operations, command and control, how’s it going to work in a distributed environment. But we need these test articles and we need to bring these on quickly so we can actually see how this is going to work,” Crites said, adding that, though largely undefined still, the need to procure these two USVs now “comes from the fact that, as we look to the way distributed maritime operations is going to work and how we’re going to fight a future fight, we’re looking at what these investments need to be and what we need to bring on, and this is one of the things we need to bring on. And to do it, I need to get started on it so that we can actually develop all the documents” that would lay out more programmatic details.

The shipbuilding budget also includes funding for four LCU 1700 surface connectors, as well as $648 million for the refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) for USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74), which is set to begin in 2021 when USS George Washington (CVN-73) exits its RCOH at the Newport News Shipbuilding yard in Virginia.

However, the budget plan states that the next carrier, USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), would not be refueled and instead would be used until its nuclear fuel is spent, sending it to an early retirement later in the 2020s. Several media outlets have reported that this decision was a Pentagon-level decision, not one the Navy wanted to pursue.

“As part of this budget request, we made the difficult decision to retire CVN 75 in lieu of its previously funded refueling and complex overhaul (RCOH) that was scheduled to occur in FY 2024. This adjustment is in concert with the Defense Department’s commitment to proactively pursue diversified investments in next generation, advanced, and distributed capabilities, including unmanned and optionally manned systems, and to provide a strong industry demand signal for the same. This approach pursues a balance of high-end, survivable manned platforms with a greater number of [complementary], more affordable, potentially more cost-imposing, and attritable options.”

Crites said the decision to not refuel Truman saves about $3.4 billion in procurement costs within the five-year Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) about about $2 billion in procurement beyond the FYDP, as well as about $1 billion in operations and maintenance for every year the Navy does not have to operate a carrier and its air wing. Still, he declined to categorize the move as a budget-related one, rather saying that the decision to retire Truman was “biased … towards the future, mindful that we still have time to respond to further analysis. There is a force structure assessment (FSA) and other work ongoing that will help us validate this decision.” He later noted that “we are focused on some of these future capabilities that we need to get, and we need to get after it today,” and that this year’s FSA will help the Navy “prove to ourselves that we’re making a good decision” by reducing the size of the carrier force.

Still, as recently as early February, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson spoke of the value of the carrier strike group even against a high-end adversary like China, which has advanced long-range weapons that could threaten the aircraft carrier operating close to its shores or islands outfitted with missile launchers.

“The big thing that’s occupying our minds right now is the advent of long-range precision weapons, whether those are land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles, coastal defense cruise missiles, you name it. and those weapons connected with a kind of a reconnaissance strike network that’s becoming more and more capable,” Richardson said Feb. 6 at the Atlantic Council.

But the advent of directed energy weapons and a more capable carrier air wing through the F-35C carrier-variant JSF “is going to make [carriers] a much more difficult target to hit. So I would say, rather than expressing the carrier as uniquely vulnerable, I would say that another way to express that is that it is the most survivable airfield within the field of fire. This is an airfield that can move 720 miles a day, that has tremendous self-defense capabilities, and if you think about the sequence of events that has to occur to target and hit something that can move that much, and each step of that chain of events can be disrupted, from the sensing part all the way back to the homing part.”

The FY 2020 budget request includes $1.7 billion for Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) design and advance procurement. The funding covers detail design efforts, continuous missile tube production and advance construction on major hull components and propulsion systems.

Between FY 2020 and 2024 – the extent of the Future Years Defense Program outlined in this budget request – the Navy requests only two Virginia subs a year, whereas last year’s request included a third one in 2022. The plan also drops to just two Arleigh Burkes a year in 2021 and 2022 compared to previous plans for three a year.

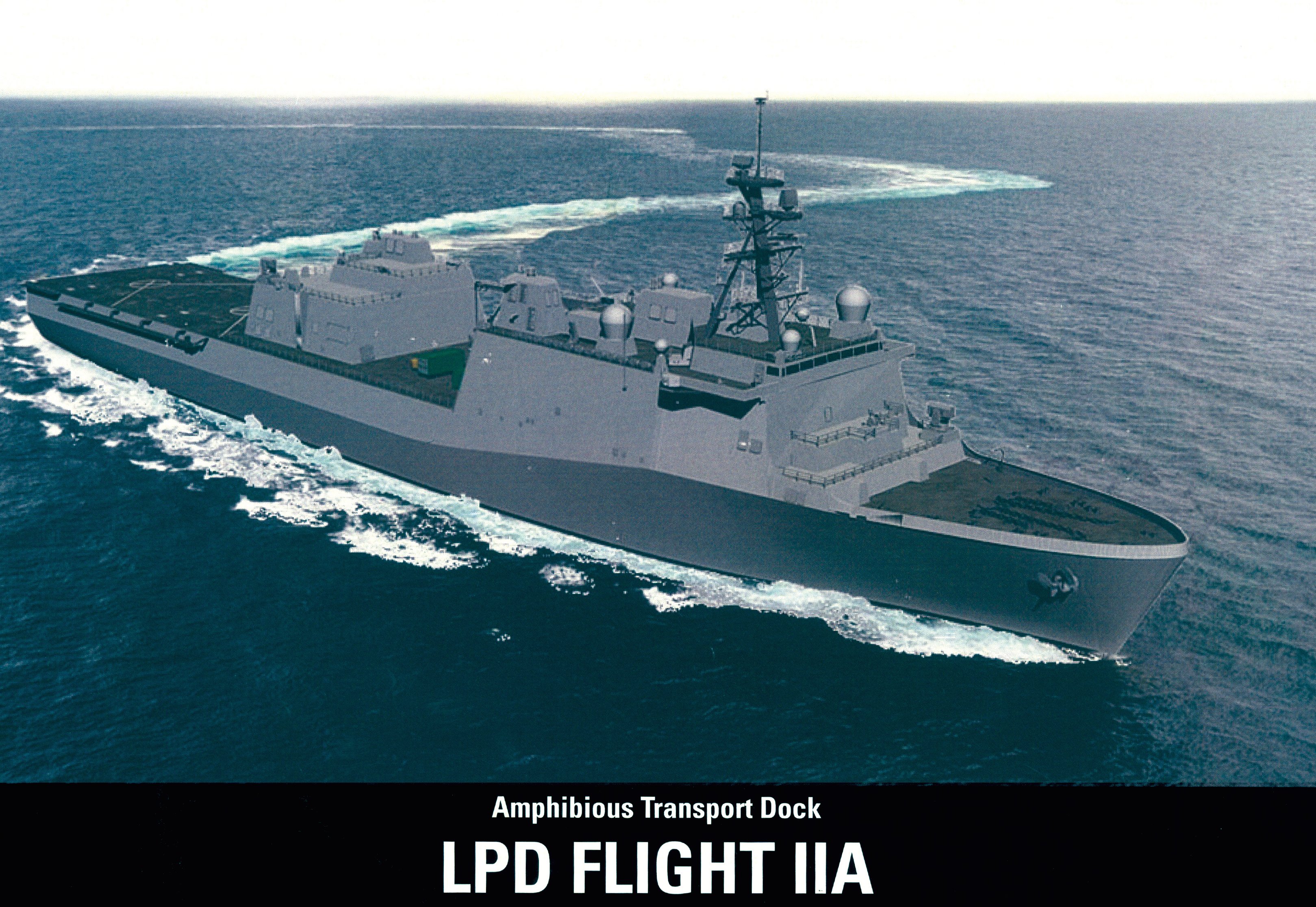

The request delays LPD Flight II amphibious transport dock procurement and does not lay out a path to enter into a multiyear contract as the Marine Corps and industry had been pushing for. Rather than asking for the lead ship in 2020 and then serial production beginning in 2022, this year’s plan calls for a single ship in 2021 and a single ship in 2023. These LPD Flight IIs will use the same production line as the original San Antonio class and will replace the less capable Whidbey Island-class LSDs.

The budget also retains a 2024 procurement date for amphibious assault ship LHA-9, whereas the Marines and industry had hoped to bump that up to allow for continuous production at the Ingalls Shipbuilding yard in Mississippi.

The budget also delays the next Expeditionary Sea Base. It accelerates the frigate program somewhat, asking for two ships in 2021 instead of the previously planned one.

Aircraft Procurement

The Navy plans to spend $18.6 billion in FY 2020 to buy 148 aircraft. The request includes:

- 20 F-35Cs, a four-plane increase compared to last year’s FY 2020 plan.

- 10 F-35Bs, a 10-plane decrease compared to last year.

- 24 F/A-18E-F Super Hornets.

- 4 E-2D Advanced Hawkeye airborne early warning aircraft.

- 6 P-8A maritime surveillance aircraft, a three-plane decrease from last year’s plans.

- 3 KC-130J cargo and refueling aircraft

- 22 F-5E/F light supersonic fighters the Navy and Marines are buying from Switzerland to serve as adversary aircraft during training.

- 6 CH-53K heavy-lift helicopters for the Marine Corps, three fewer compared to last year’s plan.

- 10 CMV-22B Ospreys that will replace the Navy’s C-2A as the carrier onboard delivery aircraft.

- 32 Advanced Helicopter Training Systems, an increase of five compared to last year’s plan.

- 6 VH-92A presidential helicopters.

- 2 MQ-4C Triton unmanned maritime surveillance aircraft, a decrease of one compared to last year’s plan.

- 3 MQ-9A Reaper unmanned aircraft the Marine Corps is buying to begin training its unmanned aerial systems operators to work with large Group 4/5 UAVs.

The Navy’s spending plan shows further decreases to aircraft procurement in the out years. The F-35B program for the Marines was cut by 10 in 2020, five in 2021, three in 2022 and one in 2023. The Navy’s Super Hornet program is kept steady with last year’s plans in 2020 and 2020 but cut by nine in 2022 and five in 2023. The Navy’s F-35C procurement totals remain steady with last year’s plan from 2020 through 2023, but eight aircraft are shifted from 2021 to later years.

Crites said during his press briefing that the cuts to the aircraft procurement over the FYDP were partly due to trying to find the right balance of tactical aircraft and changes the Marine Corps made to its squadron transition plan between the F-35B and C variants. He added that affordability concerns also shaped the decision to pare down from last year’s plan.

“There was a little bit of affordability in there. We’re trying to build a balanced program, and by balanced I mean I’ve got to have everything: I’ve got to have the people, I’ve got to have the munitions, I’ve got to have the readiness across the board. So we have the constraints we have within our topline, and we went after this in an analytic way to build the best program we could, and this is where the chips fell out,” he said.

Readiness

The Navy plans to spend $57.7 billion on operations and maintenance in FY 2020. That sum includes a 5.5-percent increase in ship operations funding that would cover an average of 58 days underway per quarter for ships on deployment and 24 days per quarter for ships that are not deployed, Crites said.

Noting challenges in ship maintenance in recent years – including backlogs at the public shipyards forcing more attack submarines to go into private yards for work – the Navy is requesting $12.5 billion in total ship maintenance funds, including $668 million to support submarine repairs in private yards. The Navy has said that planning to put submarines in private yards ahead of time, instead of waiting until the backlog at the public yards gets so bad that the service’s hand is forced, is a better use of money and gets subs in and out of maintenance faster. Crites said the 2020 ship depot maintenance funding request represents a 6.8-percent increase compared to 2019 and equals 95-percent of the need, or the maximum executable level.

Additionally, Crites told reporters, the Navy will spend $2.7 billion over the FYDP and $454 million in FY 2020 alone to upgrade and optimize its four public shipyards that work on nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers. The 2020 funding includes $250 million for modern repair equipment and tooling and $204 million to modernize the drydocks and shiphandling support equipment at Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The budget also supports reaching the Navy’s goal of having 36,100 full-time equivalent employees across its four naval shipyards in 2020.

The Department of the Navy is also asking for $1.32 billion for aircraft depot maintenance and $1.25 billion for aviation logistics. These sums reflect higher maintenance costs for the F-35 and the V-22 compared to the aircraft types they replace, and they support the Pentagon’s effort to achieve at least 80-percent mission capable rates for aircraft by the end of FY 2019. Crites said the aviation depot maintenance funding is down slightly compared to FY 2019 based on the aircraft and engines awaiting depot maintenance this year, but he noted that key readiness drivers such as logistics, spare parts and engineering support are funded at the maximum executable levels to achieve as much readiness as the Navy and Marines can get.

Air operations funding increased 4.2 percent over 2019, or about 25,000 flight hours, Crites said, in a nod to having more ready aircraft available for pilot training and operations.