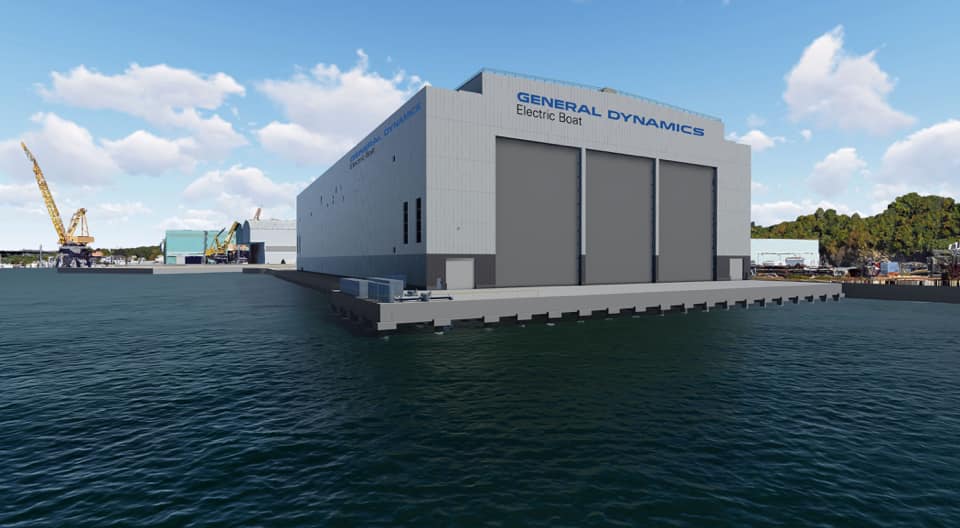

GROTON, Conn. – General Dynamics Electric Boat broke ground on a Columbia-class submarine assembly facility at its Groton yard on Friday, kicking off one of the final facilities improvement projects the company needs ahead of a massive increase in submarine construction work in the coming decades.

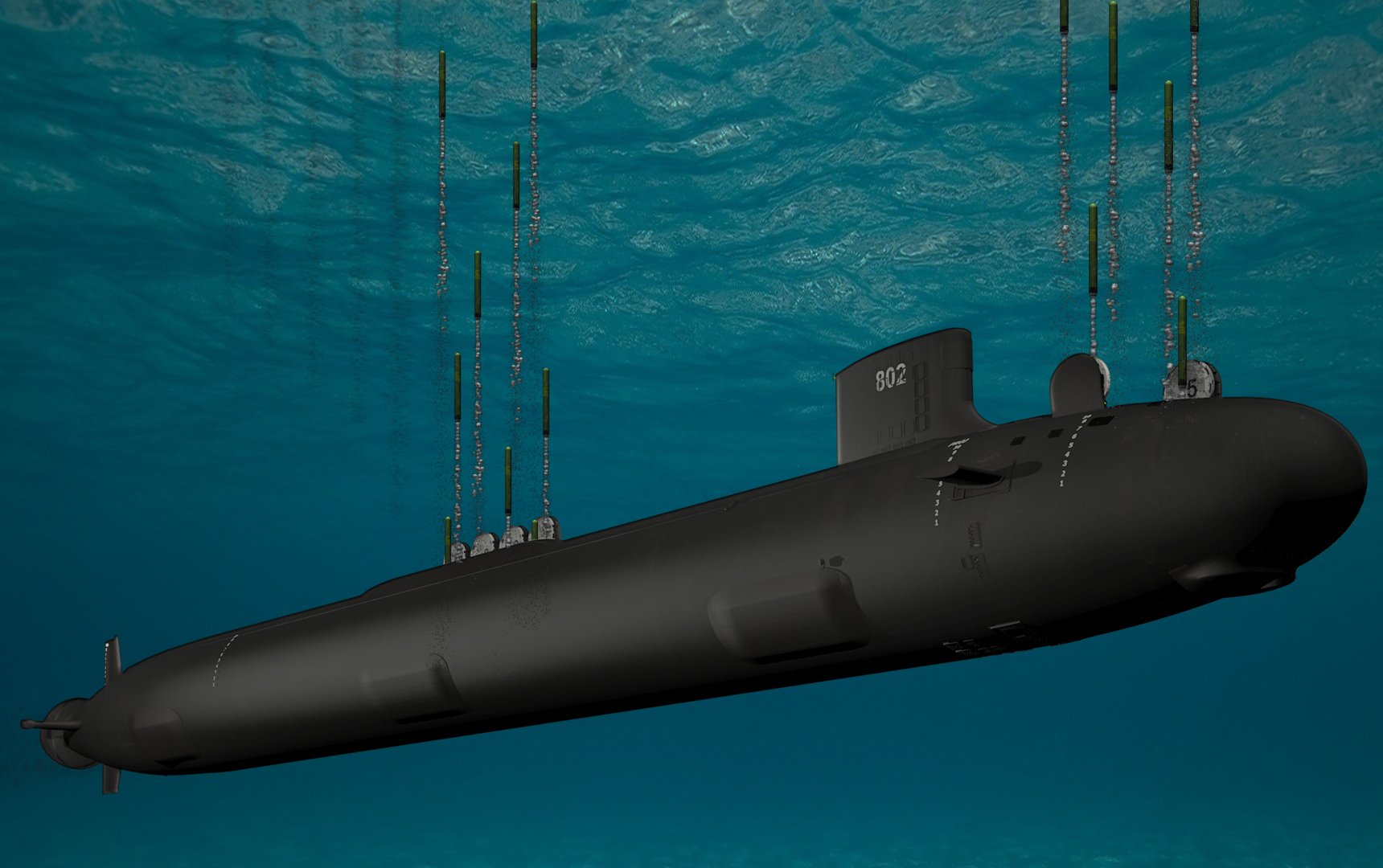

Electric Boat and fellow shipbuilder Newport News Shipbuilding together will see a 250-percent increase in submarine tonnage that they will deliver to the Navy between 2017 and 2036 compared to the 20-year span before that. The increase is due to the Navy buying more Virginia-class attack boats, adding into the SSN design an 85-foot Virginia Payload Module (VPM) that contains 28 missile tubes, and building the Columbia-class of ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs).

The Columbia assembly building, coupled with a Virginia Payload Module special fixture building and additional module construction bays at the company’s Quonset Point yard in Rhode Island, marks among the final steps Electric Boat needs to take to get the yards physically ready for the bump in workload.

However, other challenges remain that are harder for the company to control: chiefly, fragility and risk in the supply base.

“We’re really into a new era of shipbuilding that is going to be a back-to-the-future kind of event for us: the last time we did a multi-program construction of submarines started basically in the ‘70s and it lasted a little bit more than 20 years, 25 years or so. And we’re going to do the same thing in the next 20 years,” Tom Plante, the director of strategic planning for Electric Boat, told USNI News on Sept. 13 ahead of the groundbreaking ceremony for the Columbia assembly building.

That 20-year stretch of sub-building from 1977 to 1996 included both the Ohio-class SSBNs and the Los Angeles class of SSNs. The submarine industrial base churned out 4.2 subs a year on average, and 767,250 tons of undersea capability in total.

Though the two shipbuilding yards involved and the fundamentals of managing two programs simultaneously remain the same, the capacity of industry to build submarines is greatly diminished from this heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, Plante said.

“We don’t have the breadth of capability out there we had the last time we did this. We went from 4.2 submarines per year – between us and Newport News we delivered 62 [Los Angeles]-class submarines and 17 of the 18 Ohio-class SSBNs in the period between 1977 and 1996 – that’s 4.2 submarines per year between us and Newport News. Then we went into a low-rate production period. Berlin Wall comes down, Cold War ends, peace dividend, Navy cancels the Seawolf program. So starting in 1997, and going all the way to 2016, between us and Newport News the average delivery of submarines was 0.8,” he said.

“A lot of people left the business, and we went from a very robust supply base to one that’s very challenged, with 80-percent sole-source suppliers. We lost sources of supply all over the place.”

The last time Electric Boat and Newport News worked on two types of submarines at once, they had 17,000 suppliers, he said. Today the supply base stands at just 3,500, heading into the 250-percent increase in workload to achieve 2.3 subs a year and 524,750 total tons of submarines.

Among those suppliers, 324 have been assessed as “critical” for the submarine programs and are being carefully monitored for their ongoing capacity and quality of work.

Plante said Congress will continue to make money available to Electric Boat to invest in weak spots in the supply base through facilities upgrades and workforce training for critical suppliers and to encourage additional companies to join the market to supplement sole-source providers of critical parts.

However, it may be too late.

Start of construction at Electric Boat for the first-in-class USS Columbia (SSBN-826) is set for Fiscal Year 2021. However, advance construction and procurement activities typically start about two years ahead, meaning that suppliers of components big and small for the Columbia and Virginia programs are already seeing their workload jump, and if they can’t keep up today, one or both production lines could face delays down the road.

Plante, explaining the cadence of work at the yards and the need to stay on schedule, referenced the “I Love Lucy” episode where the title character works at a chocolate factory. Lucy and friend Ethel, unable to keep up with the pace of the conveyor belt, find themselves furiously grabbing candies off the line, eating them and shoving them into their uniforms to keep unwrapped chocolates from making it to the next room. “I think we’re fighting a losing game,” Lucy says.

“You remember the scene where she’s in the candy factory? If we screw up our cadence, our schedule, that’s what’s going to happen,” Plante said.

As the Navy and industry ramped up from one boat a year to two with the Block IV Virginia program contract, the supply base already saw some inability to keep up with the line, and the ripple effect is ongoing now.

“It kills us,” he said of “the Lucy effect” with Block IV.

“We were challenged to meet our schedules in Block IV, and some of that is program execution, some of that is ripples caused by [continuing resolutions] and funding and plus-ups. … If we get off that rhythm, if we get off that cadence, that causes these ripples, and it takes multiple ships to work through that. If you have a supply problem – non-conforming material comes in and I’ve got to stop, I’ve got to go assess, I’ve got to rip things out, I’ve got to re-do things – then that all adds time and cost to construction execution by shipbuilders.”

“There may be a cost associated with replacing the material,” he added, “but the biggest impact is the labor it takes through introducing inefficiencies, these ripples.”

Plante worries that adding VPM and Columbia could create an even worse strain and program delay.

Groton won’t have to worry about churning out its first fully assembled submarine until 2027. Quonset Point won’t deliver its first Columbia module until 2024, when for the first time workers there will make six modules a year for two Virginia subs as well as five modules a year for a Columbia sub. But suppliers are running a couple years ahead of that schedule, meaning some are already working on parts for Columbia now.

Whatever deficiencies exist in the supply base, it is unclear if some of them will reveal themselves with the addition of the first Columbia submarine, or later when Columbia hits its stride and reaches a one-a-year pace, or perhaps not at all.

“What I would tell you is that everybody kind of feels the supply base because of the timing: they’re early, not a lot of investment’s gone there. That’s one of the higher areas of risk in the program execution. If you don’t have that material on time, you cannot build the ship, no matter how many facilities you’ve got ready or how many people you’ve got ready,” Plante said.

“We all feel that we’re behind in the supply base because they are in front of us on demand, and we’ve been late to get money for supplier development. [General Dynamics] is investing $1.7 billion in facilities, and that’s sucking up a bunch of capital, but we’re at least in control of that. Our suppliers, we’re not in control of their boards; we have to convince them this is real and it’s in their interest and we’re going to work with them, and then they’ve got to go through the same process of getting agreement from their boards to make this investment.”

Construction Requirements

As laid out in the most recent Navy shipbuilding plans, the sea service wants to buy two attack subs a year for the foreseeable future. With a shortage of SSNs now that will only get worse before it gets better, the Navy is also looking for opportunities to add a third sub a year into the program – if it can be done without throwing off the delicate balance of Virginia and Columbia work at suppliers and at Electric Boat and Newport News.

The first SSBN will be bought in 2021, with the second coming in 2024, the third in 2026 and then serial one-a-year procurement through the end of the 12-sub program.

In total, this means at least 29 more Virginia subs and 12 Columbia subs in the next 20 years, beyond the 11 Virginias already under contract and in various stages of completion.

Once the Virginia Payload Module is added into the Block V boats, though, those subs will require 25-percent more work that Blocks I through IV. And the Columbia subs constitute about 2.5 times more work than an original Virginia sub. So whereas today the yards are delivering two Virginias a year, in 2027 and beyond they will deliver the equivalent of 5.3 subs a year.

Today’s backlog of 13 subs in various stages of construction will grow to 20 – which will be the workload equivalent of 30 original Virginias.

While the shipbuilders had worked hard to get SSN construction down to a goal of 66 months, the first Block V sub with VPM will take 74 months before coming down. The first Columbia is planned for 84 months, and the learning curve should take that down to 70 months.

“We’re right at the precipice of climbing that mountain,” Plante said from his Integrated Enterprise Plan War Room, covered on all walls with shipbuilding plans, acquisition plans, build plans for both types of subs, facilities plans, cost estimates, cost-reduction strategies, supply base and supplier quality charts, ideas for outsourcing upcoming work at Quonset Point and more.

“We should be able to do this,” he said, but he noted that the Navy and Congress have to do their part too.

“We’ve got to have funding show up when it’s supposed to, we start construction when we’re supposed to. It’s very important that these ships stay on this cadence, boat over boat over boat, because we don’t want to get jammed up in the assembly line.”

Facilities Requirements

Plante’s war room charts show the more than 25,000 activities – manufacturing, installation, testing and more – that it will take to successfully deliver a Columbia sub, each already attached to a date. That means he knows what supplies he’ll need to accomplish that, what workers he’ll need, what money – and what facilities.

“We facilitized Quonset already for Virginia two-per-year,” he said, referring to the Block IV contract that moved from one a year to two a year.

“But now I’m adding 25 percent more work scope to them. So they’re going to need more facilities for that big VPM module.”

The VPM facility at Quonset Point just completed construction and will soon be outfitted with all the machinery needed to build the new section, which will contain 28 missile tubes.

The VPM shop is a 30,000 square-foot, $28-million facility that is part of a larger $700-million investment announced last year to increase by 13 acres hull-outfitting space for the Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines at Quonset Point. The project, which is still ongoing, will add 575,000 square feet for module construction. Once complete, modules are put on a barge and shipped down to either Groton or Newport News Shipbuilding’s yard in Virginia for final assembly.

The Columbia assembly shop in Groton will be the only one of its kind: while Newport News and Electric Boat alternate which yard conducts final assembly on SSNs, it was decided early on that, due to the small number of boats in the Columbia class, the program would only invest in a single SSBN final assembly facility.

The larger modules for the SSBNs mean Electric Boat has to invest in a heftier ocean transport barge to carry them – the modules are beyond the capacity of today’s Sea Shuttle to carry. The rivers leading to Quonset Point and Groton will also likely need dredging work to allow for the bigger barge to get in and out.

The Groton yard will also need a sinking basin and a floating dry dock to support getting the SSBNs out of the assembly facility and launched into the river, and both those projects remain on EB’s to-do list.

“We can build facilities, obviously there’s some risk … in getting this new facility. The United States hasn’t built a floating dry dock like what we’re talking about in 35 years. Most of those come from China or Korea or Japan, so that’s kind of new,” Plante said.

Still, despite some work to do, facilities is one of the less-risky items for the Columbia program.

“We’ve made good progress in getting ready to build the ship. A couple risk areas: facilities was one of those, so today is a big step in the right direction in making sure we have the facility capacity to do it,” Program Executive Officer for Columbia Submarines Rear Adm. Scott Pappano told USNI News after the ceremony.

“Stepping one step back, there’s still a significant ramp-up required in the workforce, here at Electric Boat and in Newport News Shipbuilding, to make sure we have the right number of people to build the Columbia and all the Virginias we have to build. So the workforce exists, it’s getting those people in, getting them trained, making sure they can do the work as early as possible.”

Workforce Requirements

Electric Boat has a plan mapped out to ensure it has enough workers at Quonset Point and Groton to cover the booming workload. Each location has its own challenges, though.

At Quonset Point – where pipes and other materials for Columbia are already being produced alongside parts of SSNs – the workforce sat at about 2,000 when the Navy transitioned from one SSN a year to two. It has already ramped up to 4,250 today, on its way to about 6,000.

Plante said Quonset Point will be capped at about 6,000 workers due to the limitations of the facilities and parking. Electric Boat in 2013 already bought the last remaining parcels of land nearby for its expansion. With a workload of about 8,000 workers expected, the Quonset Point facility will need to outsource about 4 million hours of work a year to keep up with the cadence of six Virginia modules and five Columbia modules a year during the peak of production.

For the Groton assembly yard, though, the workforce challenge is somewhat trickier.

While the company would, theoretically, want to start hiring new workers and training them soon, the yard is actually facing a dip in planned work ahead of a steep increase in 2024. The planned engineered overhaul of USS Hartford (SSN-768) beginning in 2021 will help ease the valley ahead of the mountain of work, but a gap in 2023 remains.

“We don’t want to let anybody go,” Plante said, adding the company continues to look for ways to flatten that workload out. Taking on another maintenance availability would help some but would not exercise all the skills needed to build a new sub. Taking on another post-shakedown availability would help more, he said, but new construction work would be best. The time has passed where adding another Virginia boat would help, since the modules wouldn’t show up for assembly in time, so they hope to find ways to pull ahead work on the first-in-class Columbia, such as shipping some modules to the yard in smaller pieces so that assembly work can begin in Groton ahead of schedule.

The yard already has significantly less experience per employee than it did previously: the average worker at Groton had 23 years of experience in 2010 and just 13 now, and the average Quonset Point worker had 15 years of experience in 2010 compared to 7.6 now.

Coming into so much workload, Plante said the last thing the yard needs is to lay off more people ahead of an increase in work, and the addition of new work that hasn’t been done since the 1990s. He said Electric Boat is entering “the World Series of shipbuilding” and is in “game 1” right now, and it needs all its best talent to succeed.

“The Columbia doesn’t hit this waterfront in a major way until February of ‘24. Once February of ‘24 happens, we’re going to have five modules come in in a year, and this place is going to get pressurized; I want seven-, eight-, nine-year people in here.”

The company has hired 14.818 total people since 2011 for both facilities, and as a result the company has moved from about 47 percent of the workforce being baby boomers to 50 percent today being millennials. With many new workers not sticking around, the company is making more of an effort to do more up front to help potential hires understand what life at the shipyard will be like. They are also working with local technical high schools to add sheet metal work, piping and other shipyard trades to the curriculum, and a local community college is using the trade high school as a facility for night classes for adults looking to enter the shipyard workforce.

Despite a joint effort by Electric Boat, Connecticut and Rhode Island state governments, the Department of Labor and more, Plante said “the human capital problem is a hard one.”