ABOARD AIRCRAFT CARRIER USS GERALD R. FORD – The Navy’s newest aircraft carrier left a pier from Naval Station Norfolk, Va., late last month with its reputation arguably at an all-time low.

The world’s most modern expensive warship, loaded with unique and largely unproven technology designed to reduce manning and increase strike fighter sorties over its predecessors, has faced months of bipartisan criticism in Congress.

Members of both the House and Senate defense committees have used the delayed development of USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), a $13-billion warship, as an exemplar of what’s wrong with shipbuilding and defense spending.

“The Navy entered into this contract in 2008, which, combined with other contracts, ballooned the cost of the ship to more than $13 billion without understanding the technical risk, the cost or the schedules,” Senate Armed Service Committee chairman Sen. Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.) said at Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael Gilday’s confirmation hearing.

“This ought to be criminal.”

In October, Rep. Elaine Luria (D-Va.) called Ford a “$13-billion nuclear-powered floating berthing barge.”

Outside of the Hill, President Donald Trump has expressed skepticism on the electromagnetic launching system, and the delay in activating the ship’s first-of-a-kind advanced weapons elevators and other issues may have hastened the exit of former Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer. As it stands, the Navy has a path to complete the elevators but it won’t be until the end of its 17-month testing period.

“Ford is something the president is very concerned about,” Acting SECNAV Thomas Modly said last week at the Naval Institute’s Defense Forum Washington.

“He talks about a lot, talks to us about a lot. I think his concerns are justified because the ship is very, very expensive and it needs to work.”

For its part, the Navy has been largely quiet while its premier shipbuilding program has taken it on the chin in the press and has been blasted by the Hill and the White House.

Until last month.

USNI News was part of the first group of reporters underway aboard Ford and given status updates on the major pieces of technology that the service says will make the ship the most deadly carrier in history.

Keeping to Schedule

Ford skipper Capt. J.J. “Yank” Cummings had one goal for the carrier’s first 20 days underway after completing sea trials: leave on time, come back on time.

Cummings took command one month into the carrier’s repair period that was planned for one year but was extended six more months to wring out problems ranging from the carrier’s nuclear propulsion plant to the Advanced Weapons Elevators.

Before the repair period, “a lot of times the Ford came back early for some casualties that were major,” the fighter pilot turned ship commander told USNI News two weeks ago during an interview in the carrier’s robin egg blue in-port cabin, modeled after the genteel 1970s living room of President Gerald Ford’s home in Michigan.

In particular, the carrier suffered a major propulsion fault during sea trials in January 2018, forcing the ship back to port.

Now, since completing the post-commissioning repair period that was extended, “we left twice on schedule and came back on schedule, no issues,” he said.

“Are there still things we’re working on? Absolutely. And we’re going to bust their butts to get [the crew] ready to go and get the ship ready to deploy as soon as possible.”

Moving ahead, the crew of the carrier will work to fine-tune the new technology on Ford, Program Executive Officer for Aircraft Carriers Rear Adm. Jim Downey told USNI News aboard the carrier.

“There’s a couple dozen ‘first-ofs’, state-of-the-art systems on their ship. When you build such a new complex ship, the ship is the testbed. We need to get out there and operate,” Downey said.

“So for me, it’s, finish up the last work remaining, and support the ship and operations, and that’ll write its own story.”

The primary focus of Ford in the first months of 2020 will be certifying the flight deck for the aircraft that need to be launched and recovered using the ships Electromagnetic Aircraft Launching System (EMALS) and Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG).

Meanwhile, the contractors and the crew will be working to make real the promise of the new technology on the carrier and work past the previous stumbling blocks.

“I would say that, yeah, we’ve hit the bottom, we’re scooping it out now and now we’re working hard to improve the … reputation of the ship,” Cummings said.

More Planes, More Bombs, More Problems

The Ford-class is set to improve over the 1960s-era Nimitz-class carrier design with a focus on a singular goal – maximizing the number of strike aircraft the carrier can fuel, arm, launch and recover.

Acting on a mandate from then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, the Navy included several unproven technologies on the ship.

When the Navy was developing Ford, the service spent years studying the flow of ordnance, fuel and aircraft on and underneath the flight deck to increase the most important metric of the carrier: how many armed strike aircraft it could launch in a 12-hour period, or its sortie generation rate. In addition to in-house talent, the Navy famously consulted NASCAR pit crews on how to tighten up their process to keep the aircraft moving.

The goal of the service was to increase sortie generation rates by 30 percent compared to the Nimitz class in a day of flight operations.

“That’s 120 sorties sustained on Nimitz to 160 on this ship. That’s sustained, not surge,” Downey said.

Instead of four aircraft elevators to carry planes from the ship’s hangar to the flight deck, designers realized they just needed three.

“As we analyzed the design, it wasn’t about getting the aircraft to flight deck,” Downey said. “That wasn’t an impedance to higher sortie generation rate; it was getting the bombs to the aircraft and then the aircraft off the flight deck.”

Those requirements pushed the Navy to develop three key technologies that would not only increase the sortie rate but also reduce manning levels on the carrier: EMALS, AAG and the Advanced Weapons Elevators.

While each subsystem has faced the scrutiny of not only Congress but also the Pentagon’s own Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E), perhaps no system has drawn more attention lately than the weapons elevators.

Advanced Weapons Elevators

Like the other technological innovations on Ford, the weapons elevators are designed to serve the overarching sortie generation metric, Downey told USNI News.

The new elevators are a generational leap from the old cable and pulley elevators on Nimitz. The platforms move up and down rails via permanent magnet motors using the same technology as high-speed levitating monorail trains.

“It moves at more than twice the rate than Nimitz elevators,” Downey said “[It] handles twice the weight of the Nimitz elevators –14,000 pounds roughly on Nimitz, approximately 28,000 here. And the maintenance related to that hydraulic system is gone, and because of the [design] you can actually seal off each deck because that rope system isn’t there.”

The underlying technology is sound, the Navy has stressed. The holdup is having the elevators work correctly with an irregular series of doors and hatches that have been designed to maximize the efficiency of moving ordnance from the bowels of the ship to new staging areas just below the flight deck (on the Nimitz-class, weapon assembly happens in the mess decks) to ultimately top side. The elevators delivered so far travel the short distance from the weapon assembly areas to the flight deck. The harder issue is to work the elevators that run five levels down to the ships’ fore and aft magazines.

There are in total 70 water-tight, multi-ton doors that have to work in concert with the 11 elevators.

“They have very, very tight survivability specifications, thousandths of an inch of flatness on a multi-ton door and how it interfaces with the hull. [They’re] airtight, watertight,” Downey said.

“As you work on a multi-ton door like that, you could work quite a while, flattening that door perfectly, measuring it and doing all the related tests.”

The delay in certifying of the elevators has been a key point for critics of the carrier since former Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer told reporters that he made a promise to President Trump at the sideline of the 2018 Army-Navy Game that was first reported by USNI News.

“I shook his hand and said, the elevators will be ready to go when she pulls out or you can fire me,” Spencer said in January.

As of last month, Ford had four out of 11 weapons elevators that have been turned over to the crew from the shipbuilder.

Downey said work on the elevators was about 75-percent complete and would be worked on for 18-months of testing and certifications. The Navy has taken on more than 100 shipyard workers to complete the elevators while the ship is underway.

“The ship is gone 50 percent of that time… Some of it is heavy industrial work. So, the shipyard and the Navy have a month at a time, roughly, to work on the ship pier-side here at Norfolk Naval Station,” Downey said.

“Folks have asked, ‘Well, why didn’t you just leave the ship at the shipyard and finish the elevators in a quarter or two?’ That’s a valid issue to discuss. But we wouldn’t have exercised anything else on the ship.”

The elevators were cycled more than 1,000 times throughout the 20-day at-sea period, Downey and Cummings said.

In 18-foot seas, the crew cycled the deepest elevator more than 30 times with “no issues whatsoever,” Cummings said.

The repeated tests are rebuilding faith of the crew in the systems.

“That’s a thousand times in the last 20 days versus 3,000 times the whole nine months before,” Downey said. “So the ship is meant to be at sea and exercise, and that’s really what’s going on.”

Electromagnetic Aircraft Launching System

Perhaps in second place to the scrutiny of the weapons elevators is the futuristic catapult system on Ford – the Electromagnetic Aircraft Launching System (EMALS).

In 2017, President Trump told Time he was skeptical of the system and wanted to replace EMALS with the old Mk-13 steam catapult system. He has since repeatedly expressed doubt in the system.

Despite the scrutiny and early developmental delays, the Navy is bullish on the system. The launching system can not only launch aircraft faster than the old steam catapults but also requires less manning and allows more precision in operations.

“From the shooter’s perspective, operationally, it is simpler down here,” Ford’s Air Boss, Cmdr. Mehdi “Metro” Akacem, told USNI News from a launching station nested in the ship’s flight deck.

“In a steam catapult it’s old school, steam-punk style analog. You’re checking weights of aircraft, wind over the deck conditions, doing table lookups. … That table look-up gave you a value to put into a hydraulically actuated valve that controlled the rate at which a steam valve or a major steam valve opened. And based on that rate, that was how much force you were getting.”

Instead, EMALS allows the shooter to set a set desired end speed for the launcher based on the type of aircraft that is ready to go, and then launch with the computer driving the system and constantly making adjustments to the speed based on sensor readings. Akacem told USNI News that, in the hundreds of tests performed on the ship, the end speed hasn’t been more than a tenth of a knot off.

Below the flight deck, the spaces that would contain the guts of the Mk-13 have been replaced by racks of power generators that collect electricity from the reactor and quickly dump off the energy into the EMALS. Spaces that required 16 sailors during flight operation are now overseen by one or two sailors via closed-circuit cameras.

“Below deck is operationally where you really have a difference,” Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Equipment) 1st Class Justin Knighton told USNI News from his station below the flight deck.

“Previously you’d be coordinating efforts between multiple work centers, multiple catapults, several personnel. You have [to work] lots of valves. You have to work with a gang to make sure that your steam alignment is correct, with the right pressure, temperatures, PSIs, everything. That’s a constant thing. Whereas here I get power from the reactor. Once I have that power, that’s it,” he added.

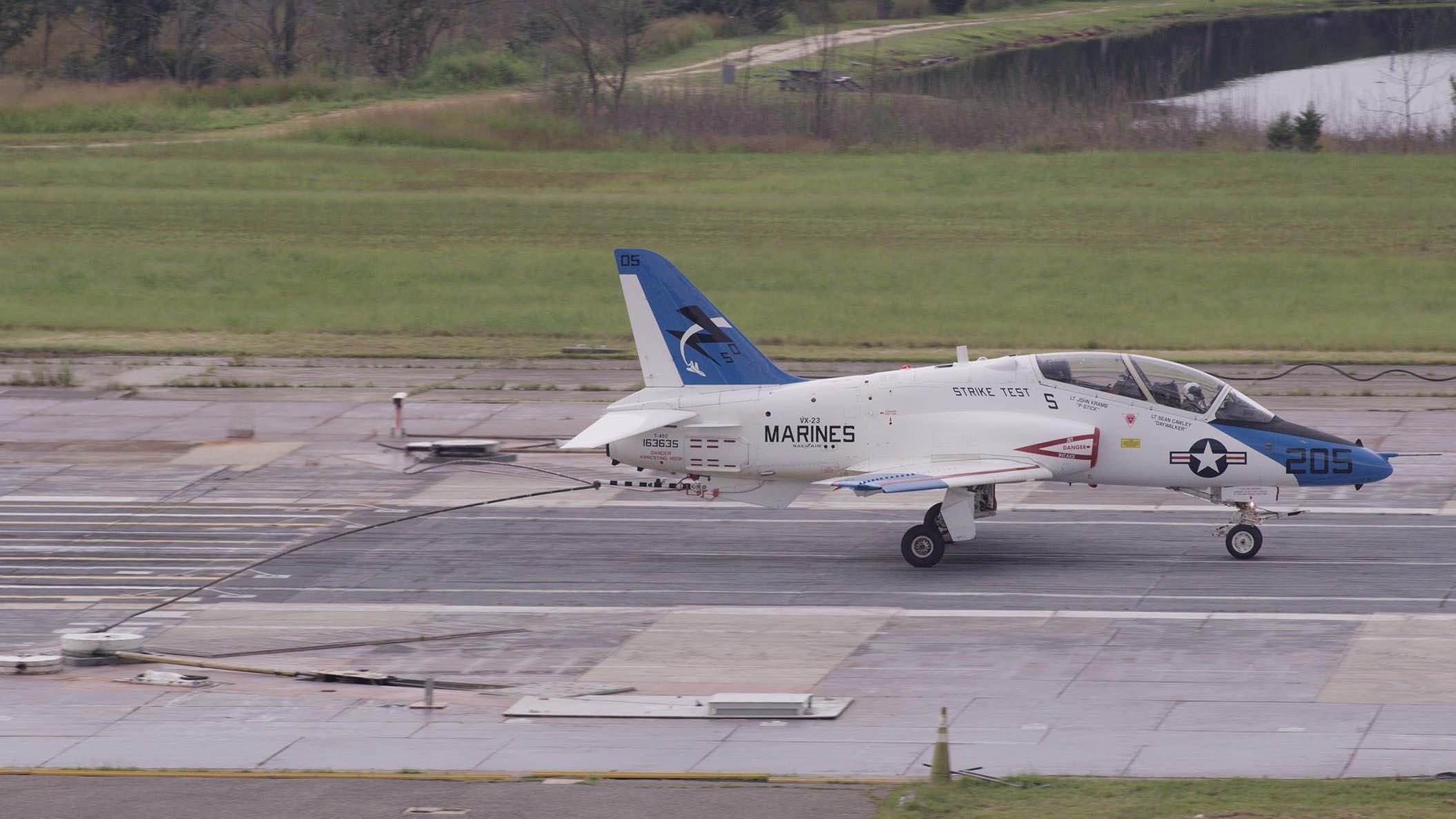

While Ford was in the yard in Newport News, the Navy used its EMALS land-based test facility at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey to generate the launch and recovery bulletins for the fixed-wing aircraft that Ford will start testing within January, Akacem said.

During that time, Ford will qualify to recover the T-45C Goshawk jet trainer, the C-2A Greyhound, E-2C/D Hawkeye/Advanced Hawkeye, F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and E/A-18G Growler.

Prior to the recent repair period in Newport News, the carrier had only tested Super Hornets.

Advanced Arresting Gear

While EMALS has drawn more criticism, the Advanced Arresting Gear at the other end of the carrier has had more problems during its development.

Costs for the system that catches the tail hooks of fixed-wing aircraft ballooned by 130 percent during its development, and the Navy discovered a major design flaw in the General Atomics-built system that delayed ground testing by two years.

As recently as 2016, the Navy was considering abandoning AAG for the older Mk-7 MOD3 hydraulic arresting system.

Three years later, the crew of Ford is optimistic about the promise of the system.

While the older Mk-7s are messy air and hydraulic systems requiring dozens of sailors to keep operating, the AAG is based on electricity and water.

When an aircraft catches its hook on one of the three arresting wires, 70 percent of the force from the arrestment is absorbed by a water twister system that uses a paddlewheel in water to provide the resistance to slow down the incoming aircraft.

An electric motor and a braking system contribute to the rest of the resistance. Like EMALS, the system continues to sense the stress on the cable and adjusting the payout to compensate for an off-center tailhook catch.

“You have sensors that’s telling the main brain, which is your arresting engine controller, on where the cable is at all times. So if it has to give more motor to stop the aircraft, it can,” Chief Petty Officer Reginald Leonard told USNI News in Ford’s arresting gear engine room number 2.

As part of the testing regime at Lakehurst, EMALS and AAG will be certified for aircraft launch and recovery by the end of the calendar year ahead of the start of next month’s flight testing.

The schedule calls for the entire flight deck, including fuel systems, air traffic control and launch and recovery systems to be readay by March.

“That’s dad giving us the keys to go out and catch an air wing … without having dad here looking over our shoulder, because we’re certified,” Cummings said.

Propulsion

One of the less understood aspects of the carrier is the Ford’s next-generation nuclear-powered propulsion system. The whole ship is 100,000 tons driven by two newly designed reactors that generate 100 megawatts of power. In comparison, the legacy Nimitz-class reactors generate only about 30 megawatts.

The power inherent in the class is key to the future of the carrier. The reactors’ power gives the Navy plenty of margin to bring aboard new weapons and sensors to the ship in a relatively compact package.

One former Ford officer described the setup as “something the size of a 9-volt battery powering a Camaro.”

Given the limited information available about the sensitive aspect of the ship, USNI News understands the reactors have been operating normally but that the rest of the propulsion plant hasn’t fared as well.

Major propulsion casualties to ship’s mechanical links from the turbines driven by the steam from the reactor to the propellors during an underway period in 2017 and 2018 forced Ford back from an underway period. USNI News previously reported that one of the reasons the post-delivery maintenance period was extended was due to extensive repairs on two of the main turbine generators.

Downey told USNI News that fixes during the repair period at Newport News focused on throttle control, the main reduction gear thrust bearing that had suffered problems the crew discovered underway.

“It’s a different control system, different throttle control system. Those MRGs are made specifically for this ship, obviously, and there can be different interpretations from the factory to how it works,” he told USNI news.

“As you operate it and you get some wear or you get some discrepancy, sometimes there’s no other way to align that propulsion line off until you do it in the ship.”

Newport News was able to remachine the thrust bearing in place ahead of the most recent set of sea trials.

General Electric and Newport News parent company Huntington Ingalls Industries are in talks to sort the responsibility for the damage to the propulsion plant, while the crew says it’s largely through the major problems for the systems.

“The engines and shafts, no issue whatsoever. Worked perfectly. Imagine taking your car and going full on the gas and jamming your car to reverse and then going back and then put it to drive, stepping the gas forward and back. Did that countless times at sea. No issue,” Cummings said.

As part of the testing, the crew tested taking Ford from flank speed – more than 30 knots – to full stop and was able to do it in four ship-lengths with no issues, Downey said.

The Way Ahead

Back in Washington, acting SECNAV Modly has made getting Ford ready to deploy and fixing the material issues his number-one task in the short term, according to a list of priorities obtained by USNI News.

He called to “put all hands on deck to make USS Gerald R. Ford ready as a warship as soon as practically possible,” he wrote.

The next period of testing for Ford will be critical to ensuring the ship will be ready to pass its shock trials ahead of deployment.

“I share with crew routinely that they’re pioneers in this innovation model, and we’re leading it and looking for the next 17 months to prove that the ship is ready for deployment whenever that occurs downstream,” Cummings said.

“I want to make sure that the crew is hungry and they know that they’re a leading edge, and they’re excited to be part of the team to do just that.”

For Cummings and Downey, their progress will be under intense scrutiny.

“We just have to get after it because there’s nothing worse than having a ship like this, our most expensive asset being out there as a metaphor or a whipping boy for why the Navy can’t do anything right,” Modly said.

“We’re going to get it right. And that’s going to be one of our top priorities here.”