WASHINGTON NAVY YARD – The Navy has a more straightforward path to developing and fielding unmanned surface vessels than many critics realize, according to the admiral in charge of building them.

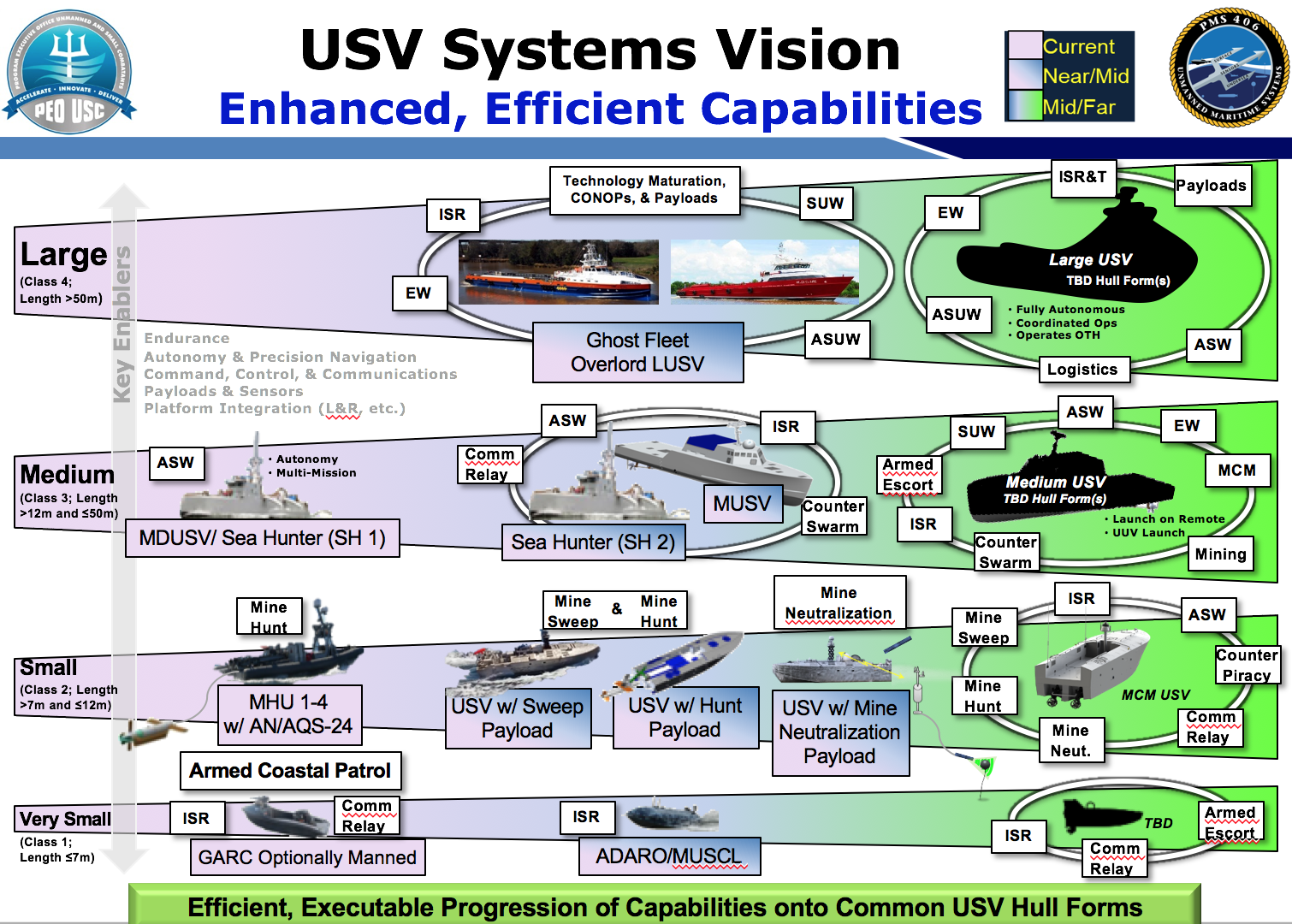

Despite the surprise and skepticism when the service announced this spring it would buy more than a dozen medium and large USVs in the next few years, Rear Adm. Casey Moton says lessons learned from commercial industry, Pentagon prototypes and existing Navy concepts are providing a good foundation for moving ahead as planned.

To build on that foundation and prepare for fleet introduction and operations, Moton said the Navy wants to hurry and invest in additional prototypes to get in the water and work out remaining work on concepts, mission package integration and other issues.

“We’re trying to buy rapidly because the need is there, but there is maybe some concept out there that we’re not as far along as we are. So I think we need to do a better job of communicating that: we’ve done a lot of work,” Moton, the program executive officer for unmanned and small combatants, said in a recent interview in his Washington Navy Yard office.

On the Large USV, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD)’s Strategic Capabilities Office already has two ships in the water, as part of an Overlord program that few knew about before the Navy announced a $2.7-billion investment in LUSVs in its Fiscal Year 2020 budget request.

Those two vehicles are conducting local transits with navigational autonomy and have undergone hull, mechanical and electrical upgrades to boost reliability and automated control, as OSD and the Navy try to understand how long such a vehicle could operate at sea without a person onboard to do all the maintenance checks, routine painting and emergent repairs that are typical on a manned warship.

Moton said the end of that early testing phase is approaching, and the Navy will begin to focus on the command, control, communications, computers and intelligence (C4I) package that may go on its eventual LUSV, which is envisioned to serve as a missile-carrier to support the Navy’s distributed lethality concept.

The Navy last week released a final request for proposals for LUSV concept design. The service plans to award multiple contracts to companies that can design prototypes that integrate common government-furnished equipment such as combat and communications systems with their own hull and autonomous operations systems. The Navy expects to buy its first LUSV in FY 2021.

An industry day in late June brought out more than 50 interested companies, Moton said, and he saw no real hurdles to moving forward on the program based on what he saw at the industry day.

On the medium USV side, which will be a distributed sensing asset, the DARPA-created Sea Hunter MUSV has already autonomously transited from San Diego to Pearl Harbor and back. The program office is working to buy another prototype this current fiscal year, ahead of beginning production in 2023.

Moton stressed that every program has risks, but that the risks associated with USV prototyping and acquisition are not nearly as daunting as people seem to think, based on the reaction to the FY 2020 budget request.

Two key fears from critics are that the technology isn’t ready and that the concepts of employment aren’t finessed.

On the tech piece, Moton assured that the machinery plant automation used on Overlord “is not rocket science” and that there’s a healthy commercial USV market already building and using this technology. On autonomy technologies, he said a lot of work has already been done in industry and through OSD prototypes on navigational autonomy and the ability to follow International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (colregs). While LUSV and MUSV may push the envelope, nothing entirely new is being created, he said.

Moton noted that reliability will be an ongoing issue, as the Navy may need its USVs to stay out at sea longer or operate farther from maintenance personnel than commercial industry requires.

Feedback from the LUSV industry day led the Navy to slightly lower its requirement for autonomous at-sea operations, based on the current state of technology, and the surface warfare directorate (OPNAV N96) will have to continue to refine its understanding of mission needs and see where those fit in with industry’s reliability improvements.

As for the concern about concepts of employment and how to integrate unmanned systems into the fleet, Moton said, “on the conops piece, yeah, I agree, that’s why we stood up SURFDEVRON,” referencing the Surface Development Squadron 1 that stood up in May and will work on concepts for unmanned ships, the Zumwalt-class destroyers, the Littoral Combat Ship and other new fleet assets.

“I talk with N96 regularly, we are working the conops piece. And yes, we’re going fast, but SURFDEVRON was meant to help with that. So the biggest thing that we need to do is get the prototypes out there quickly.”

Moton said he expects a robust discussion about how many prototypes to buy and how quickly, but he urged critics to let him get vessels in the water and prove their value.

On LUSV specifically, he acknowledged unease over the idea of an unmanned vessel firing missiles, but he said it’s not a huge stretch from capability the Navy already developed and fields today.

“Guess what? People who understand Aegis (combat system) know that for a while now we have been operating Aegis ships that have actually had autonomous firing capability since the beginning. It’s not something you would use lightly, but it’s existed,” he said.

“We already have a fleet construct where Navy ships are connected through [Cooperative Engagement Capability] and engage-on-remote, and that ships are firing weapons off of other asset’s fire control data. So the difference on LUSV is, that human in the loop, where does that human sit? That’s the difference. So there’s work to do there, but I believe we can manage, with the Overlord ships and our initial prototypes, I believe we can manage getting through that for the production line.”

Moton noted that “the initial Navy plan is to kind of put these out there to work with the battle groups to do these missions. We are not at the stage of alone and unafraid, off forever doing its own thing,” he said, though the LUSVs and MUSVs could eventually be used to push into contested waters ahead of the Navy putting sailors in harm’s way.

Despite any lingering concerns from lawmakers or other Navy watchers, the Navy’s future surface combatant family of systems is firmly committed to unmanned, with LUSV and MUSV supplementing the frigate and the Future Surface Combatant to make up the force beginning in the 2020s.

“If you look at the Navy’s distributed maritime ops and the future surface combatant force, PEO USC, we are responsible for delivering three of the four legs of the distributed maritime future combatant force,” he said, with the Future Surface Combatant being the only one to fall under PEO Ships.

Moton said when took command of the PEO in May, a key focus was getting the RFP out for the frigate detail design and construction, which happened in June.

Now, the frigate program office is working with PEO Integrated Warfare Systems and PEO C4I to develop the combat and communications systems that will be used as government-furnished equipment. An Aegis Combat System baseline will be developed specifically for the frigate, and that and other work is continuing in parallel to the shipbuilding contracting process so that the frigate program is ready for a Milestone B declaration and a contract award by the end of FY 2020.

Even as work on frigate, LUSV and MUSV continue at pace, Moton noted that OPNAV N96 is working on a new force structure assessment to revise the overall fleet size requirement, as well as a future surface combatant force analysis.

“Could there end up being some tweaks? Yeah,” he said of his three programs.

Most likely, he said, the two studies would alter the numbers of frigates or USVs the Navy wants to buy, which don’t affect his work on concept design and the kickoff of shipbuilding in 2020, 2021 and 2023, he said of frigate, LUSV and MUSV, respectively.

The studies could potentially point to capabilities changes, though, specifically for LUSV and MUSV.

“Both of them will have the capability, in some respect, for modular payloads. … So they’re being designed for the modular piece. We have a payload in mind for both of those assets, but they’re also going to have the capability to flex there if we need to,” Moton said, as a hedge to ensure that future operating concept changes don’t render the platforms irrelevant.

Moton previously worked at the PEO – then called PEO Littoral Combat Ship – as the captain in charge of LCS mission modules (PMS 420) from 2014 to 2016.

“As I come back … we still have work to do to deliver on our commitments, but certainly the (LCS) ships have transitioned – when I have my principle fleet boss out there talking about it’s time to mainstream LCS, there’s a critical mass of ships. That’s in a different spot, and I am excited to get the production done there. And I’m actually excited to work on sort of the, okay, the ships are out there delivered, what can we do to keep making them better? Mission packages have pretty much progressed to plan, the plan that was in place since I left. There have been some perturbations, some funding marks and things that have impacted us, but we’ve pretty much progressed to plan, so I’m excited about that. Clearly over the next couple years, we have to finish that, we have to do our job,” Moton said.

“The two big pieces that have radically changed since I left PEO LCS at the time are frigate and unmanned. Frigate is clearly one of the biggest things in my job jar, is to get frigate awarded and to commence detail design and construction and hopefully get to [start fab]. The team did great work on frigate; I actually think the process the frigate team used was a really effective process,” Moton said.

“The other big piece is unmanned. That’s a huge change. I mean, (the unmanned systems program office) PMS 406 was – this is probably unfair to PMS 406, but not that busy when I left PMS 420. They are now extremely busy. They’re doing a great job, by the way. … A great team, and they’re staffing up. So a lot going on.”