ABOARD GUIDED MISSILE DESTROYER ZUMWALT – One of the most conspicuous ships in the Navy is among the least understood.

Moored to General Dynamics Bath Iron Works delivery pier on May 13, destroyer Zumwalt’s (DDG-1000) stark angles towered over the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer Rafael Peralta (DDG-115) nearby. The destroyer that delivered last week displaces 7,000 more tons and is a hundred feet longer that its pier-side neighbor.

But beyond its size and its jagged silhouette, little is public about what role the ship will serve in the fleet and how a ship that was built for a world of low-intensity conflicts will fit into one that has shifted toward high-end warfare.

The ship was conceived to support Marines ashore from the littorals with twin 155mm guns firing guided rocket-assisted Long Range Land Attack Projectiles (LRLAP) more than 60 miles.

However, that role is becoming more difficult as adversaries’ anti-ship guided weapons have taken a generational leap over the last decade. Since the ship has been truncated to three hulls – from a planned class of more than 30 – the Navy has inserted technologies into the $22.5-billion program that increase the ship’s utility as a special operations platform in addition to its original land-attack role.

USNI News took a tour of the ship with outgoing Zumwalt program manager – Capt. Jim Downey – shortly before it delivered to the service last week and got an inside look at the potential the ship brings to the U.S. Navy.

Aboard, USNI News learned why almost every sailor onboard has a Top Secret clearance, where the ship keeps its anchor and where embarked SEALs would live on the ship.

‘Clean Design’

Designed to operate close to shore, Zumwalt shares several features with stealth aircraft – like avoiding curves in the design — to keep its radar cross section low.

That effort also involves keeping ship functions that would ordinarily occur on deck hidden below low-profile hatches in the ship’s tumblehome hull.

Ship designers traded the flow and curves of traditional ship hulls for stark angles that give the ship a jagged profile as it cuts through the water to reduce the ship’s size on radar screens – down from a 610-foot warship to the size of a 50 foot fishing boat, according to an April report in The Associated Press.

“As you look at the stern of the ship, what you’re seeing here are mooring stations that are open,” Downey told USNI News while boarding the ship.

“They are handled here within the ship because of the nature of the topside of the design, which is a very clean design. That relates to the radar cross section of the ship.”

Another cross section consideration is the ship’s anchor.

“You see no external anchor on the ship, it’s right centerline on the keel,” Downey said.

“That’s a mushroom-shaped anchor, very similar to a submarine’s anchor. It fits right into the hull form.“

The ship’s flight deck – twice the size of an Arleigh Burke – is free of the fixed personnel protection barriers on other ships in the fleet and instead features pop-up barriers in the rare instance the crew needs to go on the weather deck.

Even the ship’s helicopter recovery scheme is designed to bring helos into the large hangar mechanically without the air detachment traveling out on the flight deck.

The hangar – large enough to store and maintain either two MH-60 Seahawks or one Seahawk and three MQ-8C Fire Scout unmanned aerial vehicles – leads to a large passageway designed to supply the ship’s primary weapon – the Advanced Gun System.

Bringing Out the Big Guns

While Zumwalt is technically a multi-mission ship, much of the design of the ship supports the two 155 mm BAE Systems-built AGS at the front of the ship. An abnormally wide passage way for a surface ship – large enough to operate a forklift – allows the crew to move Lockheed Martin LRLAP shells easily into the ship from the flight deck following a yellow and red painted line on the deck to the ship’s weapon elevators and then down to the LRLAP magazines.

“There’s dual redundant handling systems in each magazine. It’ll grab the rounds, which are on a specially designed palette system. The rounds within the gun system are actually small missiles,” Downey told USNI News while standing underneath the ship’s aft gun mount.

“They’re each seven-and-a-half feet long and about 230 pounds for the LRLAP, and then it has a six-foot long prop charge which aids its release.”

The guns are designed to fire 10 rounds-per-minute per gun, sustained. Both guns firing at that rate would empty the 600-round magazine in 30 minutes.

The LRLAP “is a gun-fired guided missile. There is no equivalent to this round anywhere else in the world,” an industry source told USNI News last week.

“It has been tried before and failed, but this the only naval guided gun-fired projectile and performs flawlessly.”

Early tests of LRLAP have been positive, but the Navy has been reluctant to talk about the cost of the rounds. Later this year, the service plans to issue a limited production contract to Lockheed to purchase test rounds for Zumwalt’s initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E). Ultimately the Navy is expected to buy just 1,800 to 2,200 LRLAPs for the planned three-ship class.

While the Navy won’t talk about LRLAP costs, several sources told USNI News the price range for the rounds could be from $400,000 to $700,000 per round. In comparison, a Raytheon Tomahawk Land Attack Missile with a range of 1,000 nautical miles is about $1 million.

In a 2002 promotional video for the AGS, a potential fire mission called for 12 rounds to strike an urban target. At $500,000 per LRLAP, the 2002 scenario would cost about $6 million in munitions. Multiple fire missions could bring the total for a day of operations – just for munitions – easily into the tens of millions of dollars.

The Navy has explored alternative rounds for AGS, Downey said.

“It’s not impossible, but you can’t directly fire [other rounds] out of that barrel without modifications,” he said.

“There are studies to look at other rounds, but none of that is in the program right now.”

Naval Sea Systems Command is considering installing an electromagnetic railgun on the third Zumwalt — Lyndon B. Johnson (DDG-1002), NAVSEA commander Vice Adm. William Hilarides Naval Sea Systems Command told USNI News in 2015.

Ship of Secrets

The ship’s main command and control space looks more like the interior of a black box theater rather than a traditional combat information center (CIC) on a modern cruiser or destroyer.

About twenty operational consoles – like the terminals on a modern destroyer or cruiser with an upgraded Aegis combat system – are arranged in rows ahead of three giant monitors in the two-story space. In addition to the combat system operators, the ship’s engineering division also makes their home in the ship’s mission center. Aft and above the main mission center are twin spaces used for mission planning for use of embarked command staffs or other units assigned to the ship.

The spaces above the mission center floor are glassed off so personnel can see the main screens – like a luxury box in a sport’s stadium – but not disturb the crew operating the ship.

The entire space is classified as a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF), which is one reason the ship’s crew needs the highest clearances to operate on Zumwalt.

“The majority of the crew has to have the most highly classified clearances, Top Secret essentially,” Downey said.

Other features aboard that add to the security are the ability for the crew to access classified networks from their staterooms, which are protected by special locks to prevent unauthorized entry.

Part of the secrecy comes from the design of the ship’s network and part from the sensitivity of some of the missions the ship could be tasked to do, Downey said.

Those potential Special Operations missions are evident in the ship’s boat dock. Large enough to handle two rigid hull inflatable boats, the space also contains berthing for a SEAL detachment and features a decontamination station in case personnel encounter dangerous chemical and biological agents on a mission.

The ship’s shallow stern allows recovery of the RHIBs while the ship is underway at 12 knots in up to 15-foot seas.

Given the low radar cross section and the ship’s ability to operate close to shore, Zumwalt could conceivably be a credible special operations insertion platform like how the service uses its guided missile and attack submarines, Bryan Clark, a naval analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and former aide to retired Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert, told USNI News last week.

“Originally because the class had this focus on the littoral, it seems like there was always some expectation that they may do special ops off the ship. It’s always been focused on littoral environments and some of those things were baked in at the beginning,” Clark said. The additional features the Navy has added over the last ten years appeared to have increased the special mission emphasis.

Power Margins

The most unique feature of Zumwalt is its integrated power system (IPS). Shedding the traditional direct mechanical connection from a destroyer’s gas turbines to its props, the ship’s four gas turbines – two Rolls Royce MT-30s Main Gas Turbines (MGT) and two Rolls Royce MT-5s Auxiliary Gas Turbines (AGT) – feed into two massive Advanced Induction Motor which electrically feed the rest of the ship’s systems.

“Via the two MTGs and the two ATGs you have the capability of producing 75 megawatts of power on the ship,” Downey said during a tour of one of the engineering spaces.

“In other ships you would have propulsion capability via reduction gear to turn the shaft and you would have separate generators on the ship to provide power to the ship’s systems.”

With the ship moving at 18 to 20 knots, the ship has a surplus of almost 58 megawatts – enough electricity to power a small town.

The surplus power margins, plenty of space on the ship and additional cooling surplus allows Zumwalt to take on additional systems in the future without an extensive redesign.

For example, the Navy is in the midst of a redesign effort to find power and cooling for the new Raytheon AN/SPY-6 Air and Missile Defense Radar on the existing hull form of the Arleigh Burkes.

Part of those margins comes from the classes’ unique (and controversial) tumblehome hull, which creates a wider beam that can accommodate additional systems.

Tumblehome Throwback

No aspect of the Zumwalt class has come under more criticism than the ship’s tumblehome hull design. Instead of riding over waves like the traditional naval hull, the tumblehome hull cuts through waves while maintaining increased stability in most seas.

No aspect of the Zumwalt class has come under more criticism than the ship’s tumblehome hull design. Instead of riding over waves like the traditional naval hull, the tumblehome hull cuts through waves while maintaining increased stability in most seas.

In the last year, several reports have quoted maritime museum and traditional ship design experts who have questioned the stability of the design.

Downey told USNI News that the requirements of the ship necessitated the hull type.

“[The] equipment, the acoustic signature, the radar cross section requirements drives you to this hull form,” he said.

“[Tumblehome] is the only way the best naval architects and designers could get to: how do you have the least bow wake, stern wake and reduce radar cross section.”

During the 13 days, the ship has been underway during trials, the ship proved to be stable in seas of up to 13 to 15 feet (Sea State 5), he said.

“It’s designed to handle better than anything we have in the U.S. Navy. Better sea keeping than anything we have,” he said.

Ship commander Capt. James Kirk told USNI News during the tour that, while underway, at high speeds a hard rudder turn only heeled the ship about seven degrees – half that of a standard U.S. destroyer.

In extreme sea states – with 20 to 40-foot waves – modeling showed there was a limited risk of the stern lifting out of the water in quartering seas – when waves hit the ship at a 45-degree angle to its direction of travel.

“If you go fast in the highest seas and you get seas on the quarter – which worries ship drivers for every ship type – you could have an issue where the ship digs in – because of the bow – and the stern lifts and it’s not too much direct pitch, but you can get some strong ship lateral motion where the bow digs in,” he said.

In that instance, there was a chance the side-to-side motion could subject the crew to higher G forces.

However, the risk is low, as the service estimates that over the 35-year life of the ship, Zumwalt would experience waves that high over only about 350 hours of its operational life.

Concept of Operations: Then and Now

Now that Zumwalt has delivered, the service is working through how it will use the ship class.

At the moment, there are no obvious answers.

The ship is loaded with technologies that were conceived two decades ago for an asymmetric and stateless enemy that was the chief driver of U.S. military involvement. However, in the last decade, that threat has been superseded by the growing military might of China and Russia.

As the costs of the program grew, the size of the planned fleet shrank. An original plan of more than 30 shrank to nine to seven and ultimately to three, as announced by then-Secretary of Defense Bob Gates as part of the Fiscal Year 2010 budget submission.

“The trimming of the program came from – obviously the cost going up – but also the Navy over time was becoming less and less seized with this mission to be addressed,” Clark said.

For example, the 2002 concept of operations video for the AGS, the filmmakers illustrated ranges of the gun with a generic series of small islands that bear a resemblance to the Philippines – a country grappling with a decades-old Islamic insurgency.

The current technological mismatch was in part due to requirements in the early 2000s from then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Clark said.

“Rumsfeld and that crew came in, they were preaching transformation and everything had to be transformational to survive program budget review,” he said. “What that did was lead the ship to be very technologically risky and contributed to its cost overruns and its schedule delays… They gave it the electric drive and they made it stealthy and put on the dual band radar and the dual-band sonar and all of these new technologies that have mostly not been used before to try and maximize its ability to be transformational and improve its ability to survive program budget review. Technologies that they were going to put into multiple different ships and test them out now all went to one class of ship.”

One criticism recently leveled at the Zumwalt-class is the ship’s lack of anti-surface firepower. The LRLAP was originally intended to be one of several of the rocket-assisted rounds that would be launched from the AGS. Other variants would have been designed for surface targets as well as land targets, an industry official with knowledge of the LRLAP program told USNI News.

“There was early in the program an initiative out of the Navy to look at alternative gun fired rounds out of this but as the number of ships reduced, that kind of development program was unaffordable,” the source said.

The ship’s blue water punch was further reduced by a 2014 decision to replace twin 57mm with two 30mm guns set to defend against a small swarm boats.

The ship will be able to field Raytheon Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAM) and could deploy a modified version of the missile the Navy is acquiring as an anti-ship missile.

Still, Zumwalt will commission and enter the service during a time when the Navy’s destroyer and cruiser communities are fighting budget battles to put as many ships capable of high-end warfighting to sea and as reports emerge of new more lethal and complex Chinese and Russian anti-ship weapons emerge.

With less missile and radar capability than existing DDG-51s – about 80 VLS cells and no volume search radar – Zumwalt’s utility as an open-water combatant is less than its unique capability to carry out special missions.

“You’re not necessarily going to have it be an air defense ship,” Clark said.

“It’s a stealthy ship and it has some inherent ability not to be found. It’s got some air defense ability because it’s got a good radar and it’s got [vertical launch system] cells. A sneak attack isn’t going to be very successful against it and if you get into a war then you would use it differently than you would a regular DDG… They wouldn’t do regular patrols like the DDGs do, they would do intelligence gathering. They would do special ops they would do [singlas intelligence], [electronic intelligence] kinds of things, and I would use them as demonstrator platforms for new weapons and new unmanned vehicles and technology.”

One option, told to USNI News, would be to forward base two of the ships in the Western Pacific – Japan or Korea – while the third was back in San Diego.

The service has also studied using them as command ships to replace the two aging Blue Ridge-class Military Sealift Command ships.

Ultimately the concept of operations will be determined by the service’s new Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) – the Navy’s surface warfare “Top Gun” program – in the lead in cooperation with the DDG-1000 Squadron (Z-RON), a SMWDC official told USNI News in a statement.

Next for Zumwalt

Now the ship has delivered, Kirk and his crew will spend the next four months learning how to operate the ship ahead of an East Coast tour and an October commissioning in Baltimore.

Following commissioning, the ship will transit to San Diego, where it will complete activation and certification as part of an 18-month post delivery maintenance availability.

Given the schedule, the ship will probably reach an initial operational capability (IOC) sometime in 2020.

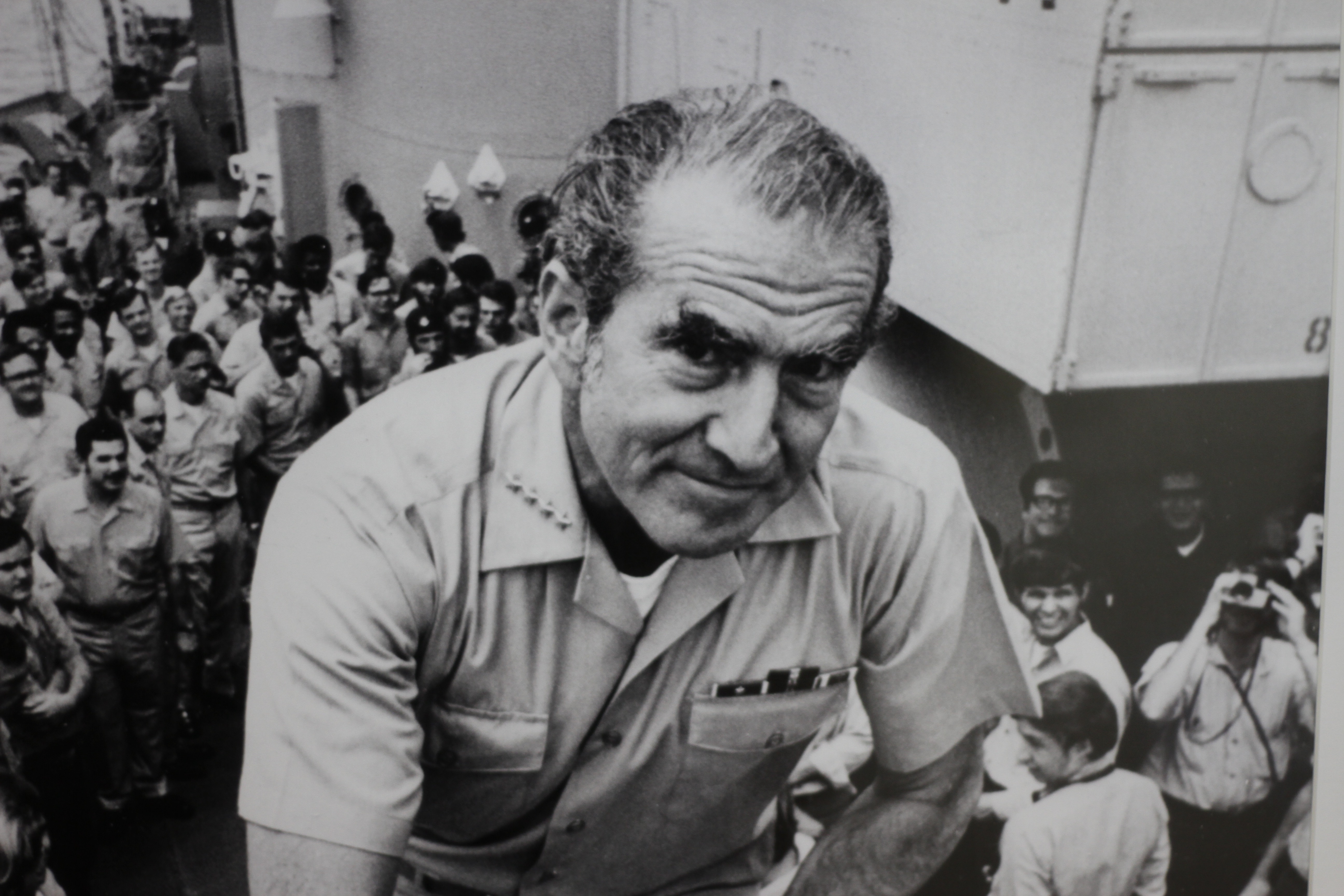

Speaking with USNI News, Kirk stressed that while the details of the technical aspects of the ship were important, so was the legacy of the namesake – former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, who guided the Navy through a rocky period during the Vietnam War.

“We’ve got a ship that’s very obviously technologically advanced to be operated with a fairly small crew,” Kirk said.

“More importantly, we’ve got a ship named after Adm. Zumwalt, a reformer of the Navy. … It’s not just a powerful ship but a powerful legacy.”