Rapid growth in the capability and quality of guided missiles — mostly Chinese in origin — is causing the U.S. Navy to rethink the number of surface ships it needs to effectively fight a high-end war.

Early estimates based on ongoing war games could mean the current number of 88 large surface combatants — the Navy’s fleet of guided missile destroyers and cruisers — needs to grow to more than a hundred into the 2020s just to keep to today’s current level of risk, USNI News has learned.

However, increasing a fleet of multi-billion dollar ships by almost 25 percent is highly unlikely given declining U.S. military budgets current funding restrictions and the wind-down from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Additionally, short-term budget decisions made by the Navy to trim spending over the next five years will leave a significant portion of its destroyer fleet less capable than initially planned. Planned upgrades that would allow destroyers to fight ballistic missiles and aircraft at the same time have been scaled back in some cases, requiring two less capable ships to do the mission of one upgraded destroyer.

Added to the increasing threat picture is a persistent lack of offensive anti-surface power on the current crop of destroyers, which either rely on aging anti-ship missiles or lack the capability altogether — leaving the current carrier strike groups reliant on its air wing for its offensive punch.

The Threat

Popular attention to the Chinese anti-surface threat has been directed at the DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) — the so-called “carrier killer.”

While the DF-21D could be an effective weapon against an unprepared surface ship, the U.S. Navy has a high probability of destroying the weapon or otherwise disrupting it from reaching its final target, experts have told USNI News.

Garnering less attention is the rapid expansion of a family of anti-surface cruise missiles (ASCM) that has occurred since the Navy underwent its 2012 Force Structure Assessment (FSA), which produced the 88-hull requirement for large surface combatants.

In the last several years, China has invested in rapidly expanding its anti-surface cruise missile (ASCM) stockpiles with an emphasis on anti-surface warfare (ASUW), according to a report on the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) capabilities released this month by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

For example, more than half of China’s submarines already can fire anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM) while submerged, according to the report.

“I’d be more worried about the many dozens of cruise missiles you could have launched at you from nearby submarines and ships than I would about the dozen anti-ship ballistic missiles that might get launched at you,” Bryan Clark, a retired Navy officer, the former special assistant to the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and now a senior fellow at CSBA, told USNI News earlier this month.

Of particular concern is the YJ-18 — a super sonic cruise missile that could be launched from a Chinese Luyang III Type-54D guided missile destroyer or a PLAN attack submarine.

The YJ-18 and other attack missiles developed in the last few years are expressions of China’s expansion beyond a military conflict based around an amphibious invasion of Taiwan to asserting its claims in the East and South China seas.

“China now has advanced supersonic ASCM deployed on subsurface, surface and air platforms,” China watcher and academic Andrew Erickson told USNI News earlier this month.

“This is a major contribution to an already thickly-layered set of Chinese capabilities designed to demonstrate ability to prevail in regional military competition over disputed island and maritime claims while deterring — and if necessary countering — U.S. military intervention by sharply raising its potential cost.”

But the threat isn’t focused solely on China. Concerns have also been raised about Russia continuing to sell high-end anti-air warfare (AAW) weapons to Iran, some details of which have been revealed in the last several weeks.

Force Structure Assumptions

For the U.S. Navy, the expansion of the global guided cruise missile capability has rendered key assumptions of the Fiscal Year 2012 force structure assessment (FSA) unrealistic — particularly around the numbers service’s fleet of guided missile cruisers and destroyers (CRUDES), USNI News has learned.

The FSA called for a total of 88 large surface combatants — the Navy’s generic reference to its CRUDES forces. In the event of a major high-end military conflict, the FSA theorized that number of large surface combatants would be adequate to provide long-range land strike and protection of high-value assets, like a nuclear carrier or a three-ship amphibious ready group (ARG), while at the same time leaving enough margin to handle other contingencies around the world.

Those assumptions were based on assigning five large surface combatants to each carrier strike group (CSG).

Those ships would be responsible for finding enemy submarines, tracking enemy surface ships, handling the air warfare protection for the carrier and tracking and destroying enemy ballistic missile threats.

However, with the plethora of new threats, the Navy is quietly mounting a new examination into the requirement for large surface combatants as part of the budget process for Fiscal Year 2017 — currently through a series of wargames.

The early analysis — USNI News understands — points to a number of cruisers and destroyers of more than 100 and an potential expansion of the CSG from five guided missile ships to seven or eight.

The reason is, the Navy’s 2012 assumptions for a high-end war in the Western Pacific were based on a smaller numbers of less capable cruise weapons and ballistic missiles coming from fewer launching sites.

Those assumptions gave the CSG a narrower band in which it had to defend against attacks.

But as more and more-lethal guided weapons are becoming available globally, as well as platforms that could deploy them, the threat axis expands further around the strike group and requires more sensors and weapons to counter the missile threats — now not just from enemy installations on shore or fighters, but also from high speed guided weapons from surface ships and submarines, as indicated by the recent ONI assessment.

In addition, decisions to leave the two emerging Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) variants without a significant AAW capability also stresses the cruiser and destroyer fleets, since the LCS could not then help protect non-combatant ships like oilers and logistics ships in an escort role, Clark said.

“We built a force structure assessment that captures the requirements to protect aircraft carriers and amphibious ready groups, and to do ballistic missile defense, and we kind of looked at LCS as a ship that would be able to do some of these escort missions for other forces,” he said.

“What that leads to in a new force structure assessment is, we’re going to need to capture what that requirement is if LCS and the follow-on frigate are not going to have the ability to protect other ships in an air defense role. What does that mean for our large surface combatant force structure if I’m having to use them to escort any other ships that are not going to be under the protection of the strike group?”

Not All Destroyers Will Be Equal

While the Navy’s 2012 large surface combatant assumptions are being challenged by more threats, the service has made decisions that will leave current ships in the fleet less capable than initially planned.

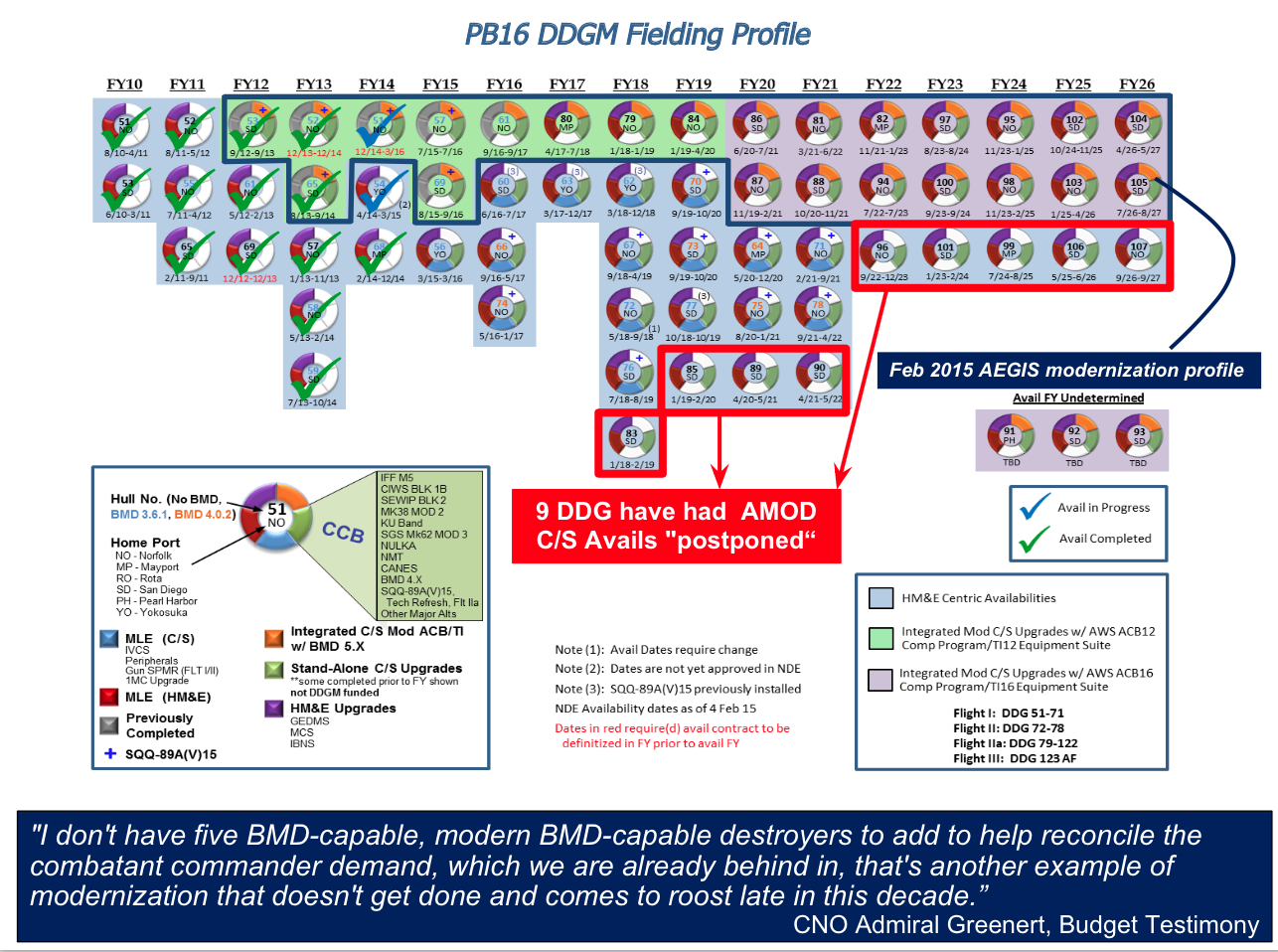

Last year, USNI News reported the service would only partially modernize the Aegis combat system for the Flight I and Flight II Arleigh Burke guided missile destroyers (DDG-51), declining to upgrade the combat system to a new standard based on modern platforms and upgrading from 1980s-era computers.

The Baseline 9 standard upgrade to Aegis would allow the ships to simultaneously conduct BMD missions as well as anti-air warfare (AAW) missions in a scheme called Integrated Air and Missile Defense (IAMD).

The Navy further downscaled their IAMD ambitions by declining to include Baseline 9 upgrades to a large swath of its most modern Flight IIA Burkes as part of a $500 million cut in modernization over the next five years.

The service elected not to modernize the combat system of five Burkes in the period, and nine over the course of ten years, Lockheed Martin officials told reporters earlier this month.

“There’s nine ships now that were supposed get a robust mid-life combat system modernization upgrade and they’re not now,” said Jim Sheridan, Director of AEGIS development for Lockheed Martin.

“The way I’ve observed the Navy balance its book is by reducing the number of modernizations they do. I can tell you back in the day, you had like four or five ships getting modernized in a given year, and that’s not the case any more. We’re lucky if you get one, maybe two.”

USNI News understands the reduction in combat systems modernization will require more ships in a CSG to perform all the missions required. While a Baseline 9 Burke can simultaneously handle a BMD and AAW mission, the service would need two non-upgraded DDGs to handle the requirements of one Baseline 9 ship.

With only two new-construction DDGs a year set to enter the fleet for the foreseeable future — according to the Navy’s most recent long range shipbuilding plan — the lack of upgrades to older Aegis ships would prompt a CSG or ARG to add more DDGs and leave fewer ships to execute the high-demand BMD mission in other regions.

Estimates fluctuate, but the demand for BMD ships from U.S. combatant commanders (COCOMs) could be as high as 70 ships — up from the current total of 33.

“Today we can’t meet a lot of what [COCOMs are] asking for because that force structure is so strained,” said Rear Adm. Jon Hill, Naval Sea Systems Command’s (NAVSEA) Program Executive Officer, Integrated Warfare Systems (PEO IWS) last week addressing a general question from a reporter on BMD demand.

“As the budget comes down and modernization moves to the right, that means we’re not taking ships and putting in the latest capability quickly. And if we reduce the numbers of ships in new construction, those curves are never going to meet… It’s a tough place to be.”

CNO Greenert addressed the modernization decision in March to reporters.

“When I bring the budget to the Secretary [of the Navy] and say ‘Here are the mandates. You saw the priorities’ and then you get to modernization and asymmetric capability and say ‘Here’s where we stand versus the other important matters that we need, I recommend that we’re going to have to defer these modernizations’ and that’s when the ballistic missile defense modernization came out,” he said.

Next Steps

With threats multiplying, U.S. Navy force structure likely to remain static and modernizations delayed or canceled, the service now is set to make hard choices on how it will handle threats to its fleet, CSBA’s Clark said.

“If you’re going to put the carrier into harm’s way, if it’s going to operate within cruise missile range of an adversary’s coast, then it’s going to be really hard to have enough capacity to defend against all the threats against the carrier,” he said.

“The problem is that if someone is going to shoot ballistic missiles at your carrier, they’re going to shoot a lot more things at it as well. Both air and surface launched.”

Clark said the Navy’s estimates from the 2012 FSA were already probably too low to protect the carrier from a well-armed adversary, and unless key ways the Navy fights its ships are changed, more large surface combatants might not be the answer.

“I don’t know if five or six cruisers or destroyers are going to make that big of a difference,” he said.

“I’m not sure if that changes the composition of the strike group because they were already operating at risk. How you deal with that is, operate those aircraft carriers in places where the threat is commensurate with your defensive capacity you have.”

In November, Clark released a paper through CSBA with suggestions on changes on how the U.S. surface navy fights.

He advocated for more offensive power in surface ships by freeing up some space in large surface combatants used by long-range AAW and BMD Standard Missiles (SM) in their vertical launch cells.

“The five or six [BMD] SM-3s you bring to shoot down ballistic missiles are not going to be the thing that makes difference and you maybe better off using terminal defense weapons against ballistic missile that get shot you,” Clark said.

In turn, surface ships would rely on more and cheaper shorter-range weapons to deal with incoming air and cruise missile threats. For example the space one long range AAW Standard Missile takes in a VLS cell could accommodate four medium range RIM-162 Evolved SeaSparrow Missiles (ESSM).

“The weapon numbers that are not high enough to fight a conflict with any of these countries. The weapons are too hard to build, to build them rapidly. The surface navy needs to look at air defense to be shorter range and new weapons that are smaller and multi-mission capable,” he said.

In part, Clark’s thesis lines up with the surface Navy’s push to maximize the offensive power in the entire surface fleet, dubbed “distributed lethality.”

Announced in January, the concept would rapidly expand high-end surface power — largely overlooked in the last 15 years when the surface fleet was mostly tasked with BMD and land strike for conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

“Distributed lethality is taking the budget that we have and making everything out there that floats more lethal. Making the trades that we need to make and making the surface navy of the next ten years, or 20 years the most lethal we can,” Rear Adm. Peter Fanta said on Tuesday at the Surface Navy Association 2015 symposium.

“[I want to] make every cruiser, destroyer, [amphibious warships], [Littoral Combat Ship], [logistics ship] a thorn in somebody else’s side.”

USNI News understands if the Navy is able to act more offensively and plan around quickly eliminating threats, it maybe able to get by with less surface ships in a high-end conflict through the attrition of enemy forces.

To that end, the Navy is moving swiftly to acquire a new crop of anti-surface missiles to replace the decades-old Harpoons the service currently uses for the ASM mission.

Still, with an annual budget outlook of about $16 billion a year for new shipbuilding, two new-build destroyers a year, reduced destroyer modernizations and the looming cost of the $100 billion Ohio Replacement nuclear ballistic missile submarine program taxing the Navy’s procurement budget — the options for expanding the surface fleet and their punch are increasingly limited.