The Joint High Speed Vessel faces several challenges in high sea states that led to difficulty transferring cargo at sea, deploying SEAL Delivery Vehicles and maintaining high ship availability, according to a Director of Operational Test and Evaluation report from September.

The JHSV, recently renamed the Expeditionary Fast Transit (EPF) but referred to by its original name in the report, wrapped up its initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E) in January 2014 but had to perform three follow-on operational test events with USNS Millinocket (T-EPF-3) because certain assets were not available during the IOT&E test window. Director of Operational Test and Evaluation J. Michael Gilmore deemed the ship “operationally effective at its primary mission of transporting troops and cargo” after IOT&E but found concerns during the follow-on testing regarding the ship’s ability to transfer goods and deploy small craft in even Sea States 2 and 3.

The DOT&E report notes that two of the three tests, in June and October 2014, examined at-sea equipment transfers between the JHSV and the Mobile Landing Platform (MLP) and its core capability set (CCS), which includes lanes for driving connectors onboard or connecting to the EPF’s ramp. MLP was also recently renamed and is now called the Expeditionary Transfer Dock (ESD).

“JHSV cannot effectively intemperate with MLP (CCS) in the open ocean. By design, the JHSV ramp can be used to conduct vehicle transfers only under conditions with significant wave heights of less than 0.1 meters (approximately Sea State 1). Such conditions are normally found only in protected harbors, limiting operations with MLP (CCS) to situations providing little operational utility,” according to the report’s cover letter.

“When tested in a more operationally relevant open-ocean environment, the JHSV ramp suffered a casualty when its hydraulic ram, used to swing the ramp horizontally, tore free from its anchor point on the transom (the surface that forms the stern of a vessel),” according to the report.

“The small amount of movement between the ships, even in the very low sea state conditions, was enough to cause the damage when a truck pinned the foot of the ramp onto the raised vehicle deck of MLP (CCS) as it transited the ramp. Vehicle transfer operations were successful in the earlier test, when MLP (CCS) was at anchor in Sea State 1 conditions inside a harbor.”

The stern-mounted ramp and the mission bay inside the EPF can accommodate both wheeled and tracked vehicles as heavy as a combat-loaded M1A2 tank. The Navy was already aware of the ramp’s sea state limitations and has devoted science and technology resources to developing a ramp for operations in Sea States 3 and 4.

Still, the report states that “JHSV is not effective for operations with MLP (CCS) unless in Sea State 1 conditions, which is an unacceptable constraint for operational deployment,” and recommends the Navy retest the interaction between the two platforms once a new ramp is developed and fielded.

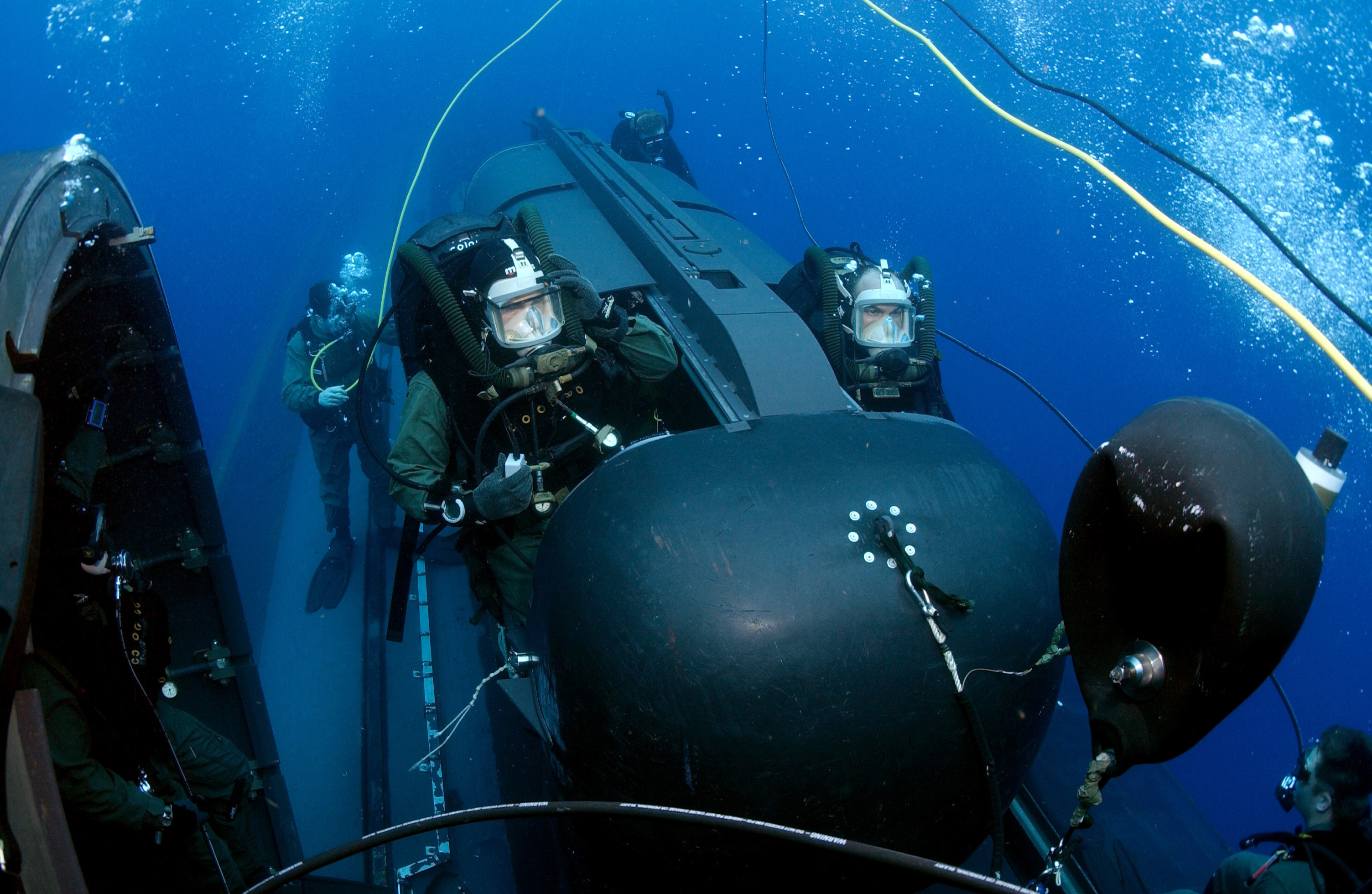

The third follow-on test, conducted in April 2015, assessed the EPF’s deployment of a SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) using the EPF’s stern-mounted crane. Gilmore noted in his report that the SDV could be successfully launched in up to Sea State 3 conditions, though he noted some safety concerns exist, such as SEALs exposure to the EPF’s engine exhaust, as well as excessive swinging during crane operations. Gilmore recommends that the Navy evaluate these safety concerns and investigate solutions.

While the SDV deployment in Sea State 3 was a success, Gilmore notes in his report that the SEALs would also have to use support surface craft to help the divers get going in the underwater SDV. Those support boats are similar to small craft tested during IOT&E, and those craft could only be launched in Sea State 2 – potentially limiting the utility of the EPF for the Special Operations Forces community.

Finally, the report notes some concerns regarding the operational availability of the ship class, both in regards to its ability to operate in high sea states as well as mechanical problems that have plagued the ship class.

“The main drivers of ship unavailability were the Ship Service Diesel Generators, waterjets, and the Ride Control System (RCS),” according to the report, which noted that demonstrated availability dropped from 98 percent during IOT&E to 87 percent after the follow-on testing – still above the 80 percent requirement, though.

“The RCS failures are a symptom of a more serious problem with the JHSV bow structure related to the ship’s Safe Operating Envelope (SOE), which is designed to limit wave impact loads on the bow structure. The Navy accepted compromises in the bow structure, presumably to save weight, during the building of these ships. Multiple ships of the class have suffered damage to the bow structure, and repairs/reinforcements are in progress class-wide,” Gilmore wrote.

“The reinforcement of the bow structure does not expand the SOE but should allow full use of the ship, within the original SOE, without risk of damage.”

The report includes images of damaged bows and notes that the first four ships in the class have already been repaired and reinforced. That effort, though, adds 1,736 pounds to the ship, which means the fuel tanks cannot be completely filled if the ship were also fully outfitted with troops and their gear. Overall, Gilmore writes that the extra weight equates to a loss of 250 gallons of fuel, or 854 nautical miles in range.

Regarding the generators, Gilmore wrote that “the ship’s electric power is supplied by Fincantieri-manufactured SSDGs, which are failing at a much greater rate than predicted. There are two SSDG’s per catamaran hull for a total of four. At least one must be operational in each hull to avoid an operational mission failure. The SSDGs were singled out in the IOT&E report because of their high failure rate, demonstrating a Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) of 208 hours.”

Gilmore recommends that the Navy “continue aggressively determining the root cause of ship service diesel generator casualties and fixing them fleet-wide.”

More broadly, the report repeats its concerns about the EPF operating in heavy wave and wind conditions. In discussing the ship’s capability and operational portfolio, the report notes that “the operational restriction of the SOE (Safe Operating Envelope) is a major limitation of the ship class that must be accounted for in all missions. To utilize the speed capability of the ship, seas must not exceed Sea State 3 (significant wave height up to 1.25 meters). At Sea State 4 (significant wave height up to 2.5 meters) the ship must slow to 15 knots. At Sea State 5 (significant wave height up to 4 meters) the ship must slow to 5 knots. Above Sea State 5, the ship can only hold position and await calmer seas. The necessity of avoiding high sea states while transiting is an operational limitation that could be significant.”

Despite these limitations, the fleet has used the new ship class extensively this year. USNS Spearhead (T-EPF-1) participated in Africa Partnership Station earlier this year, then transited to the U.S. Southern Command area of operations in support of Southern Partnership Station, Navy spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Tim Hawkins told USNI News.

USNS Choctaw County (T-EPF-2) conducted an intra-theater lift of Marine Corps personnel and equipment for Southern Partnership Station in June and recently departed for Bahrain to participate in Middle East operations, Hawkins said. And Millinocket became the first expeditionary fast transport vessel to participate in Pacific Partnership in August and has since remained in the Pacific to participate in other partnership building exercises.

During these international engagements, the ships transited the Atlantic and Pacific oceans unescorted and had no mishaps during transit or once in theater due to high sea states, Military Sealift Command spokesman Nathan Potter told USNI News.

“There have been no mishaps, however, as with any new class of ships there are unforeseen issues that arise and need to be addressed as we learn more about these capable ships,” Potter said. “For example, the need to reduce transit speeds or navigating around adverse sea/weather conditions – in order to avoid higher sea states – could be an operational limitation to consider, especially in an extremis situation.”

Potter added that sea states are a concern for all ship types but that the concern in the case of the EPF is mitigated by the ships’ intended operating environment.

“Note that the EPF ship class is intended to operate closer to shore in austere ports (i.e., littorals) and not in blue water operations,” he said, though open ocean transit issues could delay the ship’s arrival to that austere port.

The DOT&E report does not place any limitations on EPF operations and notes that it is considered operationally effective at its primary mission – intra-theater troop and cargo transfer – but makes recommendations to add to the utility of the ship in secondary mission sets.