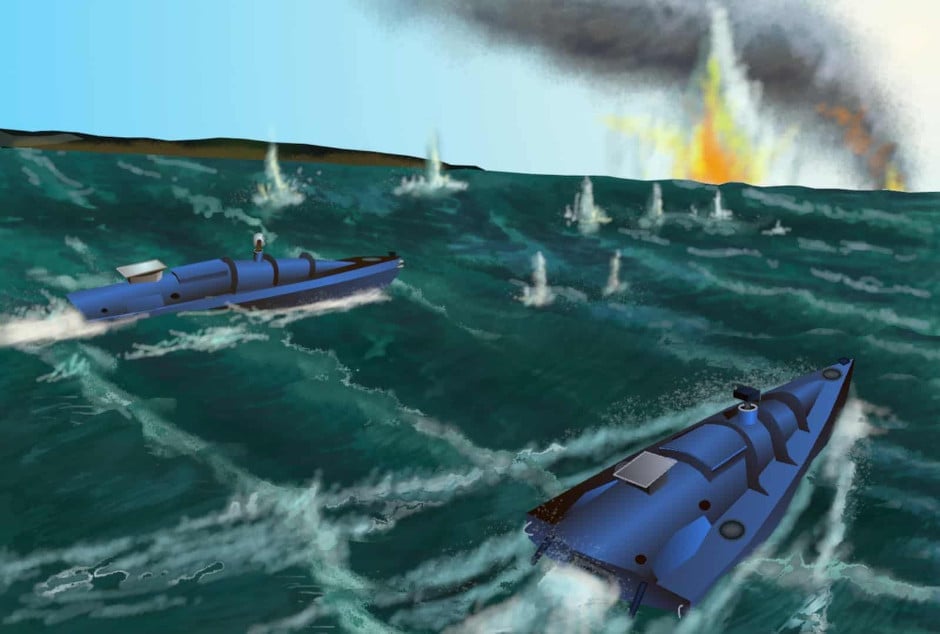

The year is 2025. China’s invasion of Taiwan, long feared, has finally arrived. America is scrambling a fleet to defend the 90-mile Taiwan Strait. But first, the U.S. military unleashes the drones.

“[Enemy] ships are getting damaged, slowing down, big timings are getting thrown off, some are getting lost, some ships are probably going to get sunk,” said long-time naval analyst Bryan Clark.

“This hellscape, this churn you cause in the invasion lets you mobilize, get your act together and start delivering the long-range fires that are going to actually take out the larger amphibious ships and surface ships,” he added.

But 2025 isn’t quite here yet.

In the summer of 2023, two Gulf Coast-built utility ships and two angular trimarans headed to Hawaii with no one at the wheel.

The quartet of autonomous ships – assigned to Unmanned Surface Vessel Division 1 – left California in ones and twos as part of what was to be a months-long deployment at the behest of U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Sam Paparo. With little fanfare, the first-of-its-kind deployment saw the quartet pop up first in Hawaii. Then Japan. And, even more ambitiously, Australia. By a long stretch, it is the biggest, longest autonomous ship deployment ever.

Led by Cmdr. Jerry Daley, the medium USVs Sea Hunter and Sea Hawk and the Ghost Fleet Ships Ranger and Mariner were on a road show to bring unmanned to the Western Pacific, marrying his division with manned warships the promise of unmanned to the fleet.

“From a training and exercise perspective we are a fully operational unit,” Daley said in May. “From controlling the vessels or utilizing the payloads that are on the vessels, [we are] completely integrated.“

The goal of the deployment was to stress the unmanned systems and craft a path to quickly operationalize unmanned systems at the urging of regional commanders like Paparo. He and U.S. Indo-Pacific commander Adm. John Aquilino have pushed the Pentagon to get more unmanned systems into the Western Pacific faster.

“We are going to continue to work through the problem sets that the fleets have,” Daley told reporters in September. “The long-term goal … is to find ways to integrate these unmanned systems across the continuum – subsurface, surface and air – while having the ability to close kill-chains faster, keep them closed longer and be able to operate in a contested environment.”

The deployment isn’t just about technology or learning how to operate such ships far from home. It’s also squarely aimed at the “near-peer” competitor in the western Pacific, China, and specifically how to stop an invasion of Taiwan.

“The concern is, can China disrupt our kill chains enough to pull off the invasion or get far enough along … that we can’t really stop it,” Clark said.

Early reviews of the unmanned deployment have been positive, USNI News understands, but the path for the Navy’s unmanned ships beyond the one-off deployment of Daley’s division is unclear.

Ranger, Mariner, their sister-ship Nomad and another autonomous ship, Vanguard, originated not from the Navy, but from a Pentagon experimental program on autonomy called Ghost Fleet. Likewise, Sea Hunter was developed through a DARPA program and is currently capped at the two existing hulls. Nomad, meant for the calmer waters of the Gulf Coast, is set to leave the fleet next year due to age, with no replacement planned.

The Navy’s follow-on program that was designed to build off the momentum of the Ghost Fleet ships, Large Unmanned Surface Vessel, isn’t due to enter the fleet until the early 2030s as part of the Navy’s current 15-year path for a manned/unmanned hybrid fleet.

However, the 2030s timeline is too late for current commanders in the Western Pacific who must prepare to defend Taiwan against an invasion from mainland China. In the so-called “decisive decade,” that invasion could come as early as 2025. Commanders want interim lethal unmanned systems to shore up the gap.

Within the last two months, the Navy and the Pentagon have created new organizational structures to connect the unmanned vision to the wider U.S. military command and control infrastructure. While operators are getting more tools to solve near-term problems, the longer-term future of the hybrid fleet and air wing is still very much an open question, frustrating both the forward-deployed Navy and the defense industry that will ultimately build the fleet, defense and shipbuilding officials have told USNI News.

“The problem is,” Clark told USNI News, “you’ve got the technologists and the operators that say ‘this stuff works today. Let’s put it to work today,’ and the people back at the Pentagon are saying, ‘let’s continue to polish this until it satisfies the perfect requirements that we’ve set up for a long-term vision of how we’re going to use them.”

A Hybrid Fleet in 15 Years

In April, former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday told reporters that starting in 2024, the Navy would procure its next set of unmanned surface vessels over three five-year budget cycles.

The service’s goal for the 1,000- to 2,000-ton corvette-sized LUSV is to act as a missile magazine and operate in concert with the Navy’s manned ships. The MUSV is a smaller ship – about 500 tons – with modular payload space. It can operate as a forward sensor node and send information to manned ships.

“The LUSV will be capable of weeks-long deployments and trans-oceanic transits and operate aggregated with Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs), Amphibious Ready Groups (ARGs), Surface Action Groups (SAGs), and individual manned combatants,” reads the Navy’s FY 2024 budget documents.

Navy requirements officials told USNI News last week that the complex new ships will require continued refinement.

“We’re not just going to wake up one day and have an unmanned fleet,” Chris Miller, a Navy civilian acting as the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), said in an interview at the Pentagon last week.

“It’s really a longer-term commitment and really trying to understand the technology and where it fits and how we deliver the most lethal warfighting Navy that we can, in close coordination with our allies and partners,” Miller said.

The LUSV, MUSV and the extra-large unmanned underwater vessel (XLUUV) are projected to cost tens of millions of dollars, operate for weeks at a time without a person aboard and have capabilities that far outstrip the simple suicide boats made famous by the Ukrainian Navy.

“[LUSV] is a fairly large program,” Miller said. “We’re going to focus it on sort of like an adjunct battery concept. That’s going to take time. I mean, I’ll be honest with people, that’s not something like what you would see in Ukraine where you take a smaller, unmanned [vessel] and make it kinetic.”

Likewise, the LUSV and MUSV programs are more complicated than the variety of leased unmanned surveillance systems that U.S. 5th Fleet has tested in the Middle East as part of Task Force 59.

The Navy is refining its overall unmanned systems roadmap that was originally released in 2021, Vice Adm. Francis Morley, the principal military deputy to the assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition, told USNI News last week in the same interview.

The systems need about that long for maturation and conceptual development “before we make large decisions on behalf of the taxpayer and convince Congress that we know what we need and what we want to build,” Morley said.

Congress was leery of the Navy moving too quickly into unmanned systems. In the Fiscal Year 2020 budget, The Senate Armed Services Committee required the service to prove LUSVs were able to operate uninterrupted for 30 days at a land-based test site before proceeding with the program.

“The committee is concerned that the budget request’s concurrent approach to LUSV design, technology development, and integration as well as a limited understanding of the LUSV concept of employment, requirements, and reliability for envisioned missions pose excessive acquisition risk for additional LUSV procurement in fiscal year 2020,” the Senate Armed Services Committee wrote in the FY 2020 defense policy report.

The first part of the LUSV testing began with converted commercial offshore support vessels originally purchased by the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office as part of the Ghost Fleet Overlord program.

SCO contracted with Gibbs & Cox and L3 ASV Global in 2018 to convert commercial ships into the first two autonomous Overlord prototypes known as Ranger and Nomad. The Navy built a third OSV, Mariner, into a Ghost Fleet vessel and is building a fourth ship, Vanguard. Additionally, Austal USA delivered a modified version of a Spearhead-class aluminum catamaran, USNS Apalachicola (EPF-13), in February with $50 million of built-in autonomous systems, mandated as part of the Fiscal Year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. The ship is currently in the Western Pacific, but – because the Navy did not specifically ask for it – is not using its autonomous system, a defense official told USNI News.

Beyond Apalachicola and the Ghost Fleet ships, there are no immediate plans to procure additional prototypes for LUSV testing, USNI News understands.

The lack of progress on both the LUSV and the MUSV after awarding a series of study contracts has frustrated some shipbuilders who were anticipating work on the smaller ships.

Some yards in the Gulf Coast are now looking to other programs, rather than waiting for finalized versions of the unmanned vessels, a source familiar with the region told USNI News.

It’s also unclear where funding for larger unmanned programs will come from in the future under projected flat Defense Department budgets. LUSV will have to compete with a new planned guided-missile destroyer, manned fighter and manned nuclear attack submarine for funds.

‘Hellscape’

While the Navy’s hybrid fleet won’t be ready until the 2030s, leaders like Paparo have a problem now:a potential Taiwan invasion.

Pacific Leaders are looking to Ukraine’s success with lethal drones made for just $250,000 and loitering munitions that have stalked and bulls-eyed Russian tanks to create a concept to buy more time and save lives.

“The country is facing the prospect of combat loss and we must be clear-eyed about that,” Paparo said earlier this year at the WEST 2023 conference. “We no longer have the sanctuary of time and distance from adversary weapons.”

To keep sailors and Marines out of the deadliest of the Pacific crucibles, they want to overwhelm the invasion force with lethal drones to create what PACFLEET calls “hellscape.” The plan calls for thousands of lethal drones on, above and under the sea, creating chaos for the invaders.

“[Enemy] ships are getting damaged, slowing down, big timings are getting thrown off, some are getting lost, some ships are probably going to get sunk,” Clark told USNI News last week.

“This hellscape, this churn you cause in the invasion lets you mobilize, get your act together and start delivering the long-range fires that are going to actually take out the larger amphibious ships and surface ships,” he added.

The concept has been taken up by the Pentagon and folded into the overarching Replicator initiative.

Announced in August by Deputy Defense Secretary Kath Hicks, the Replicator initiative will help procure thousands of cheaper unmanned systems for programs like PACFLEET’s hellscape.

“We’ll counter the PLA’s [People’s Liberation Army’s] mass with mass of our own, but ours will be harder to plan for, harder to hit and harder to beat,” Hicks said in a speech in August.

The Defense Innovation Unit will oversee Replicator and respond directly to combatant commander requests for help on operational problems. DIU is tasked with finding commercial solutions in under two years for specific Pentagon requests.

“Replicator is – in discussions so far – trying to match key operational problems, focus on specific [problems] with technology and efforts the services have ongoing that can be accelerated or grabbed or prioritized,” RDA’s Morely said. “I don’t expect to see things come out of the blue.”

Replicator’s first project will likely focus on disrupting a Taiwan invasion as a top operational requirement of both Paparo and Aquilino in the Western Pacific, USNI News understands.

The Navy stood up a DIU equivalent last month, the Disruptive Capabilities Office, with a similar mandate to solve Navy operational problems for Paparo and Adm. Stuart Munsch, head of U.S. Naval Force Europe and Africa.

“If you talk smaller scale, part of that learning, part of developing [concepts of operations] … and part of the sense of urgency of the critical decade has driven a focus somewhat on the lower end scale to get rapid capability out fast,” Morely said.

The key to both constructs is to not only acquire the systems, but also figure out how to stitch the communications, command and control together, Clark told USNI News.

“You [have] really got to focus on the command and control and the integration of them just as much [as] you are getting the vehicles themselves,” he said.

He cited the example of U.S. 5th Fleet using a variety of leased drones to create a maritime surveillance network in the Middle East.

“If you just focused on buying the unmanned vehicles, you’re only really solving half the problem,” he said. “What you saw in 5th Fleet with Task Force 59 at the time was a bunch of unmanned systems getting put out there without a really clear way that they were going to be managed or orchestrated.”

But both the Navy and the Pentagon are keeping many of the details quiet. Hicks told an audience in September that the public might not hear about any of the programs.

“It gets very sensitive very quick,” Miller said.