SAN DIEGO – An expert in electrical engineering told a Navy court that an electrical short in a forklift or some faulty batteries could have sparked the fire that ultimately led the service to scrap the former USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6), countering the Navy’s acceptance from a federal fire investigation that a disgruntled sailor deliberately set it.

Andrew Thoresen, a forensics engineer, said that in a limited, four-hour visit to the ship’s lower vehicle deck one year ago, he found a wire in a forklift’s main conductor feed had a “globule” of melted copper wires.

Such a globule likely was the result of a “localized spot” of arcing activity that would generate high heat by touching the metal framing, ignite nearby flammable materials strewn about the stowage area “and cause the damage we have in this case,” Thoresen testified Wednesday at the Article 32 preliminary hearing for Seaman Apprentice Ryan Mays, accused of hazarding a vessel and aggravated arson in the July 12, 2020 fire aboard Bonhomme Richard at Naval Base San Diego.

“We can opine this is definitely arcing, because copper melts at roughly 2,000 degrees,” he said Wednesday when questioned by defense attorney Gary Barthel. Other copper strands in two feet of wire he visually inspected weren’t melted, and “we know that it is only electrical activity that can cause that” localized pattern.

Shown in court was a photograph Thoresen had taken of the damaged wire, held in his gloved hand, along with images of the forklift and fire-damaged scene in the Lower V. “It’s definitive that it’s arcing,” said Thoresen, who’s investigated more than 3,000 fire scenes over his 20-year career.

“We know definitively it was from electrical heat and not the heat of the fire” that caused the copper to melt, he added in response to a question from Capt. Angela Tang, the hearing officer.

Thoresen also saw scores of “18650” lithium ion batteries in buckets that had been collected by investigators as evidence in the Lower V area considered a crime scene. “They’re a major fire cause that we see all the time,” he said.

But he was unable to do any lab analysis or X-ray the batteries to determine whether any of them had internal cell failure that would spark a fire, he said. None of the batteries were analyzed by federal investigators or taken to the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives lab for further inspection.

“They can’t be eliminated” as a potential ignition source, said Thoresen, a defense consultant.

His contention conflicts with an ATF investigation into the cause and origin of the fire. Just weeks after the fire broke out, and while an ATF national response team was still processing the scene aboard, a preliminary investigation concluded it was arson and not due to any accidental ignition source. The final report wasn’t completed until earlier this year.

The ATF report and a Naval Criminal Investigative Service report prompted the Navy to suspect Mays after one sailor who was standing duty in the area claimed he saw him in the Lower V before the fire was reported. Mays, who had just begun his deck department duty section aboard Bonhomme Richard when the fire broke out, has denied he started the fire.

Thoresen told Tang that he wasn’t able to do an “arc mapping” during his short visit to the ship.

It’s unclear whether the ATF team did a thorough inspection and analyses of the forklift and the batteries among the two terabytes of evidence provided to the defense. “There is no reference to [arcing] or [a] photograph that I could find,” Thoresen told Tang.

The batteries weren’t preserved as evidence that would allow analyses now, he said, and none of the investigations showed that arc mapping of electrical cables and devices in the Lower V was done that could help determine or rule out any electrical sources in the fire’s area of origin.

Case Hinges on ATF Conclusion, Witness

Fire investigators used visual examination and photographs that show varying degrees of fire and heat damage to help make sense of what happened in the Lower V area as they worked backwards from the exterior areas with less fire damage to determine the initial fire location and then the source. Other information, such as the activation and damage to embedded heat sensors in the ship’s spaces, aids them in the process, which on an 844-foot ship with 13 of its 14 decks damaged is a significant undertaking.

During testimony last Monday, the lead ATF investigator said his team that included nine other certified fire inspectors agreed that “we had an incendiary fire,” meaning it was deliberately set. That decision ruled out three other possibilities widely used by fire investigators as causes: natural, accidental or undetermined.

That conclusion, in the preliminary “fire origin and cause” finding in late July 2020, determined “the application of an open flame” ignited combustibles that were either cardboard “tri-walls” stacked near a bulkhead in the Lower V deck or vapors from liquids such as diesel or mineral spirits stored in the space, said Matthew Beals, a special agent and lead investigator.

He also said he eliminated all other possible ignition sources except for an open flame. That included forklifts and vehicles in the area and batteries. It’s unclear from his testimony, however, whether he or other investigators did in-depth inspections and analyses of those items.

Beals, a certified fire investigator, testified that he determined the fire originated along a bulkhead near two forklifts, buckets and several double-stacked, cardboard tri-wall containers between Frames 56 and 58, located between two sets of elevator bays and trunks. He contended that Mays used a lighter, which later was found in his locker, to start the fire.

But the ATF agent acknowledged that even after the final report was completed eight months later, he was “not for certain” which of those two possibilities was the ignition source. He admitted that he had no physical evidence of an open flame as starting the fire.

While investigators questioned dozens of sailors, Beals said he relied on a statement from one sailor who told NCIS investigators that he saw someone in the Lower V before the fire was first reported. That sailor, Personnel Specialist Third Class Kenji Velasco, later concluded he had seen Mays, who was on his same duty section that Sunday morning.

But Velasco didn’t identify Mays by name when he was first questioned and not until a week after the fire. Defense attorneys allege that he accused Mays because he disliked him.

Gaps Cited in Investigations

Another fire expert who testified Wednesday for the defense told the court that the cause of the fire “is undetermined.”

“I have no evidence to support … that an open flame was used, or an ignitable liquid,” said Phil Fouts, a private fire investigator and former ATF certified fire investigator.

Fouts visited Bonhomme Richard in November 2020 along with Beals and since has reviewed the two terabytes of evidence and information that prosecutors provided the defense team.

He agreed that the fire began in the Lower V, and gaps along the nearby ramp leading to the upper vehicle stowage deck created a “chimney effect” that drew heat and flames and helped spread the fire. But he said he would expand, slightly, the area of origin to Frames 53 to 61, in part due to the heat-sensor alarms’ rudimentary data that shows the area with concentrated heat and fire damage and multiple potential ignition sources. The ATF concluded the area of origin was between Frames 56 and 58.

Fouts said he didn’t have a copy of the preliminary ATF investigation, dated July 28, 2020, that he could have reviewed before he visited the ship. He criticized the ATF agent’s methods and decision to classify the fire as arson by ruling out the three other possibilities. The method Beals used, known as negative corpus, “is an absence of proof. That is not proof,” he said. The ATF “made speculations about the heat source and the fuel ignited,” but no evidence of the flame or starter fluid was found.

Fouts, who also examined Thoresen’s report, said he didn’t see “any electrical arc activity” and he didn’t do detailed inspections of the forklifts or wiring within the space. “I cannot … eliminate them” as ignition sources without further review.

The lead prosecutor, Cmdr. Richard Federico, questioned Fouts about his contentions and noted that the ATF had 10 fire inspectors as part of the national response team that spent over a week on the ship investigating the fire. Beals had testified that all 10 inspectors agreed on that initial, preliminary finding, Federico noted.

“They eliminated accidental causes. I have a different opinion on that,” replied Fouts.

Remaining Questions

The Navy charged Mays with two charges – hazarding a vessel and aggravated arson – filed under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

It alleges Mays deliberately set the fire, damaging the ship and endangering others aboard. He’s not charged or blamed for the extensive damage caused as the fire spread out of control and destroyed so much of the ship’s critical systems and interior spaces that the Navy decided several months later to scrap the amphibious warship, which was completing a $249 million overhaul and modernization for the F-35B Lightning II jet flown by the Marine Corps.

Prosecutors contend that Mays was angry over being assigned to Bonhomme Richard after he dropped out of the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL program, BUD/S, in its first week. Several crew members testified that Mays had a bad attitude, complained about being assigned to deck department and was disrespectful at times to superiors and even contractors working on the ship.

Limited testimony was heard and presented during the preliminary hearing held over three days last week. Prosecutors and investigators did not present any direct physical or DNA evidence tying Mays to the fire’s source during last week’s hearing.

Tang, after reviewing the testimony, reams of materials and hours of video interviews that are part of the evidence in the case, will make a probable cause decision and recommend further actions to Vice Adm. Stephen Koehler, the commander of U.S. 3rd Fleet. Koehler is the convening authority in the case and will decide whether the charges against Mays should be prosecuted at a court-martial, dismissed or handled administratively.

But other questions – including who else could have set the fire and why – remain.

In charging Mays, prosecutors levied the most serious charges against him that carry potential life or death sentences if he’s convicted at trial. Just since 2008, the Navy had 15 major shipboard fires, with total repairs and replacement costing more than $6 billion, according to Naval Sea Systems Command. Arson was suspected in three of those incidents – Bonhomme Richard in 2020, amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) in 2019 and attack submarine USS Miami (SSN-775) in 2012.

While the Navy has administratively punished leaders or sailors in some cases – top officers were fired after the 2008 fire aboard aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN-73), for example – few resulted in criminal charges and a general court-martial. Federal officials prosecuted a civilian worker who pleaded guilty to arson in the fire aboard Miami and received a 13-year prison sentence.

But the ensuing fire aboard Bonhomme Richard spread uncontrolled for several hours and the extensive damage led to the Navy’s decision earlier this year to scrap the amphib rather than rebuild the ship.

An in-depth Navy investigation found multiple failures across the ship’s chain of command – including poor training that left the crew unprepared to fight onboard fires – as well as delays and shortfalls in the initial firefighting response by both crew members and federal and regional firefighters.

That command investigation, ordered by U.S. Pacific Fleet and conducted under the Manual of the Judge Advocate General, was overseen by former U.S. 3rd Fleet commander Vice Adm. Scott Conn, who wrote that “although the fire was started by an act of arson, the ship was lost due to an inability to extinguish the fire.”

“In the 19 months executing the ship’s maintenance availability, repeated failures allowed for the accumulation of significant risk and an inadequately prepared crew, which led to an ineffective fire response,” Conn said. Further, training and oversight failures at different commands throughout the fleet led to the loss of the $2 billion ship. Some 36 individuals, including five admirals, were cited as being responsible for the loss of the ship due to either their actions on the day of the fire or lack of oversight leading up to the alleged arson.

The Navy has not publicly disclosed the actions taken against those individuals. A spokeswoman for U.S. Pacific Fleet in a statement last week said PACFLEET commander Adm. Samuel Paparo held an admiral’s mast for the officials singled out in the investigation.

“Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Adm. Samuel Paparo is holding Admiral’s Mast on Dec. 16-17 in accordance with Part V of the Manual for Courts-Martial. These accountability actions are taken pursuant for military members identified in the accountability chapter of the USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD 6) command investigation,” Cmdr. Rebecca Rebarich said in the statement. “As a result of the command investigation into the fire aboard Bonhomme Richard in July 2020, Vice Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO) appointed Paparo as the Consolidated Disposition Authority (CDA) to determine what action, if any, is appropriate for the military members listed in the accountability portion of the command investigation.”

“Paparo continues his duties as CDA. Once the review of all CDA matters is complete, he will report a summary of disposition decisions and actions to VCNO,” Rebarich added.

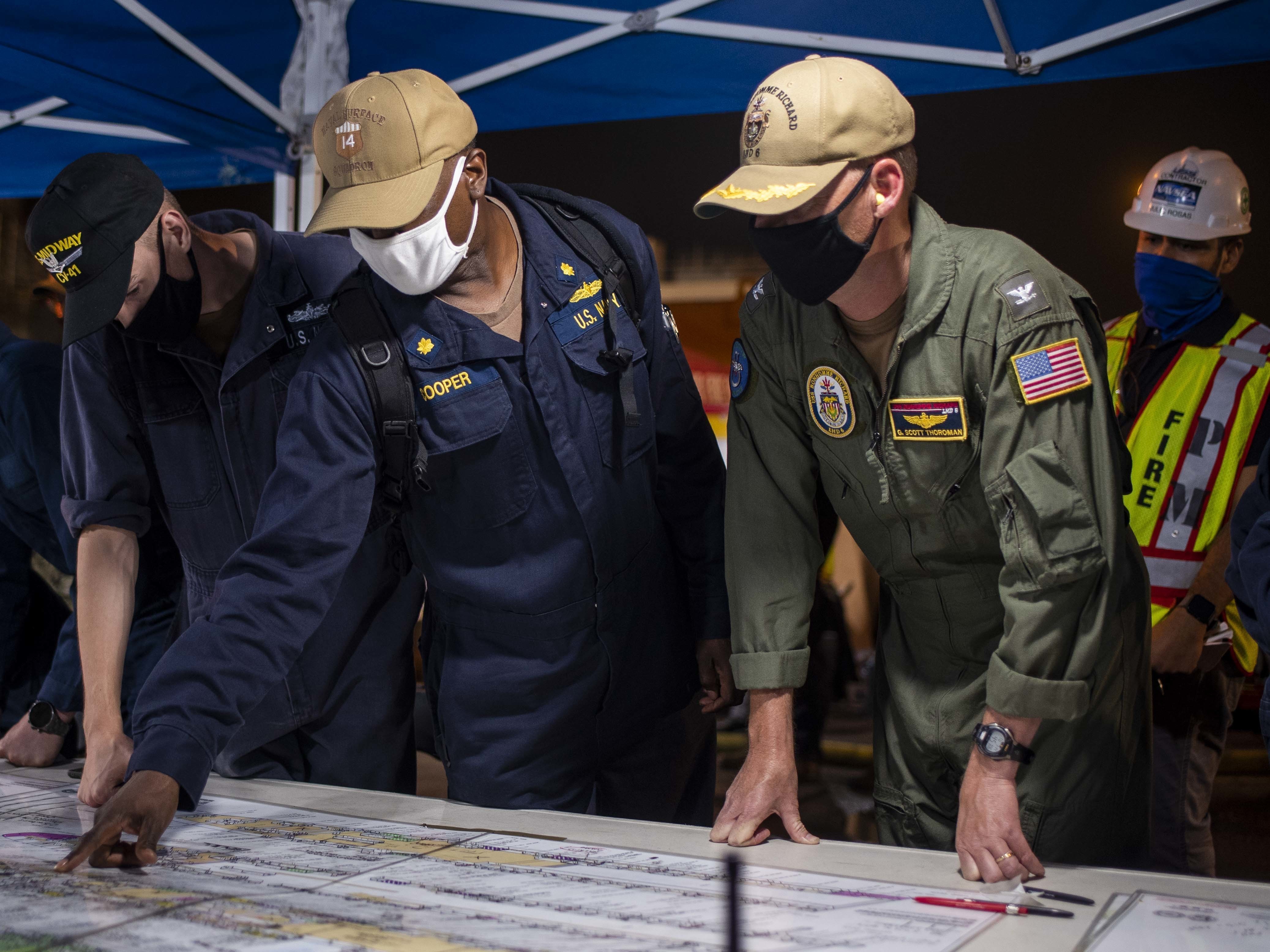

From left to right, Rear Admiral Philip Sobeck, the commander of Expeditionary Strike Group 3, Gilday, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition James Geurts, NAVSEA commander Vice Adm. Bill Galinis, Bonhomme Richard commander Capt. Gregory Scott Thoroman, Federal Fire Chief Mary Anderson. US Navy Photo

Another ‘Potential Suspect’

Attorneys and prosecutors haggled Wednesday over additional information and evidence that Tang should consider before she makes her recommendation to Koehler.

Lt. Tayler Haggerty, a defense attorney, sought to include the voluminous JAGMAN report that details and concludes that the fire spread “because of the unpreparedness of the Bonhomme Richard.”

“This happened because the ship was … a disaster waiting to happen,” Haggerty said.

But prosecutor Federico disagreed, telling Tang that it was “not relevant” to the case.

Haggerty also wants Tang to consider information that another Bonhomme Richard sailor – who a witness said she saw and recognized in the Lower V before the fire – is “a potential suspect” in the fire. Both that sailor and the witness who saw the sailor in the Lower V were interviewed by NCIS.

But Federico objected, saying that suspected sailor, who has since been kicked out of the Navy for unstated reasons, is “a distraction on the side. They also objected to evidence from that female sailor, who said she saw him on the ramp while she was returning to the hangar bay after stopping at the vending machines on a lower deck.

The charges against Mays, Federico told Mays in closing arguments, should be handled at a general court-martial.

But Barthel argued that the government has insufficient evidence to prove probable cause against Mays, who he said became a “target for false allegations.”

The ATF investigation “failed to establish that this was an incendiary event,” he said, and “created a narrative” partly from questionable witness statements and without any physical evidence.

“The government’s case is built on theory and conjecture,” he added.