A cascade of failures – from a junior enlisted sailor not recognizing a fire at the end of their duty watch to fundamental problems with how the U.S. Navy trains sailors to fight fires in shipyards – are responsible for the five-day blaze that cost the service an amphibious warship, according to an investigation into the July 2020 USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) fire reviewed by USNI News.

The investigation into the fire aboard Bonhomme Richard, overseen by former U.S. 3rd Fleet commander Vice Adm. Scott Conn, found that the two-year-long $249 million maintenance period rendered the ship’s crew unprepared to fight the fire the service says was set by a crew member.

“Although the fire was started by an act of arson, the ship was lost due to an inability to extinguish the fire,” Conn wrote in his investigation, which was completed in April and reviewed by USNI News this week.

“In the 19 months executing the ship’s maintenance availability, repeated failures allowed for the accumulation of significant risk and an inadequately prepared crew, which led to an ineffective fire response.”

Beyond the ship, Conn concluded that training and oversight failures throughout the fleet – from Naval Sea Systems Command, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Naval Surface Force Pacific Fleet and several other commands – contributed to the loss of the $2 billion warship. Conn singled out 36 individuals, including five admirals, who were responsible for the loss of the ship due to either their actions on July 12 or lack of oversight leading up to the alleged arson.

“The training and readiness of the ship’s crew were deficient. They were unprepared to respond. Integration between the ship and supporting shore-based firefighting organizations was inadequate,” wrote Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Samuel Paparo in his Aug. 3 endorsement of the investigation.

“There was an absence of effective oversight that should have identified the accumulated risk, and taken independent action to ensure readiness to fight a fire. Common to the failures evident in each of these broad categories was a lack of familiarity with requirements and procedural noncompliance at all levels of command.”

Conn highlighted the lack of adherence to the Navy’s special procedures for fire safety, which the service put in place after a 2012 arsonist fire resulted in the loss of attack submarine USS Miami (SSN-755), as a major cause of the fire.

“The considerable similarities between the fire on USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) and the USS Miami (SSN-755) fire of eight years prior are not the result of the wrong lessons being identified in 2012, it is the result of failing to rigorously implement the policy changes designed to preclude recurrence,” Conn wrote in his report.

Navy officials have said little publicly about the resulting investigations into the fire’s cause and the firefighting response by the ship’s watchstanders, the base’s federal Fire Department crews and the local San Diego Fire Department. The investigation describes the overall response on the first day as disjointed, poorly coordinated and confusing.

The revelation of the report comes after the Navy charged Bonhomme Richard sailor Seaman Apprentice Ryan Sawyer Mays with arson in July. Prosecutors say he set the fire on the ship, while his attorney says the Navy has little evidence to tie him to the crime. Mays’ Article 32 preliminary hearing is expected to be held on Nov. 17 in San Diego.

First Day Failures

An arsonist couldn’t have picked a better time to cause maximum damage to the ship, according to the investigation.

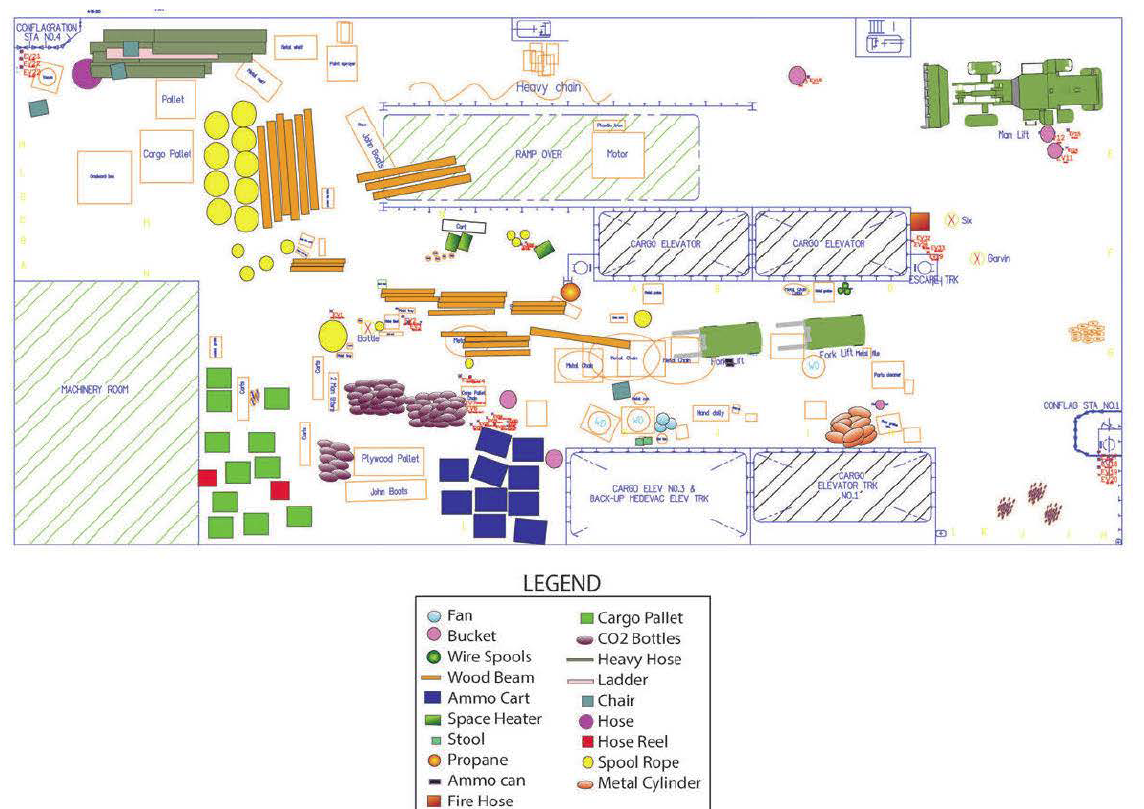

Bonhomme Richard was a ship splayed open for the shipyard availability and, as the lead investigator noted, “was particularly vulnerable to fire: having systems tagged out for maintenance; scaffolding, temporary services, and other contractor equipment hung throughout; a significant amount of ship’s gear, equipment, flammables and combustible material recently loaded onto the ship and packed into various spaces; and, more than three-quarters of the ship’s firefighting equipment was in an unknown status.”

That Sunday morning featured a small crew aboard the ship and watch sections turning over. The senior-most officer aboard was standing watch as the command duty officer for the first time. The vehicle stowage areas, used by embarked Marines to store their combat vehicles and equipment, was crowded with gear.

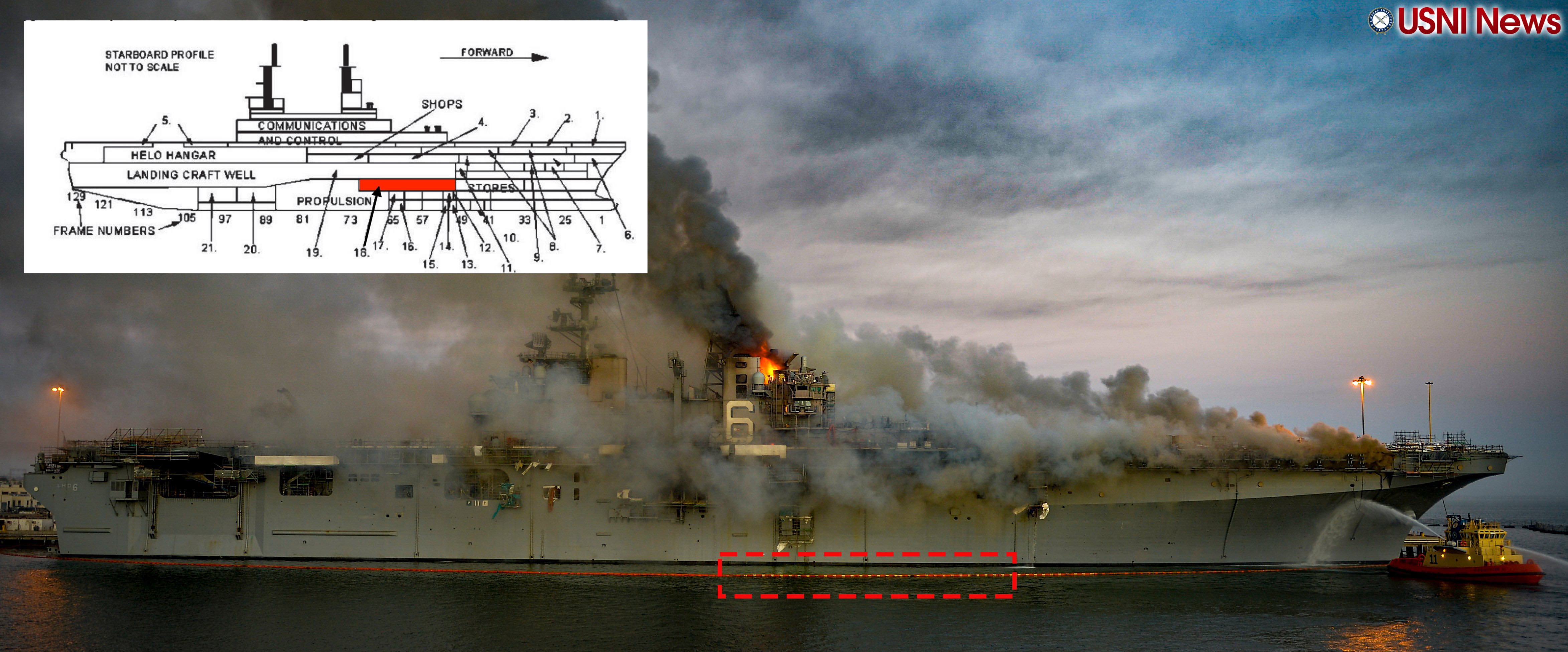

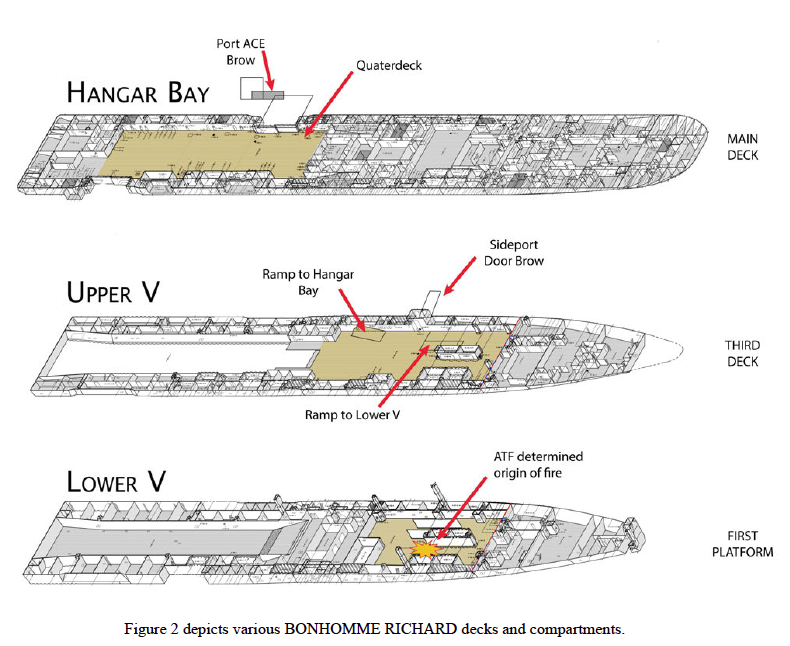

The fire began in the Lower V space, which included dozens of tri-walls filled with equipment, including plywood pallets; wire spools; wood beams; CO2 bottles; hand dollies; chairs; ammunition carts and three fueled vehicles: a forklift, a man-lift and a cargo tractor.

The first hint of trouble on July 12, 2020, came just after morning colors. Just after 8:00 a.m., a junior sailor walked through the upper vehicle deck as she headed out to a vending machine after her watch. She noticed a “hazy, white fog” in the lower vehicle deck around 8:10 a.m. But she didn’t report it, the investigation found, noting that “because she did not smell smoke, (the sailor) continued to her berthing.” Around 115 of the 138 sailors swapping duty on the ship that morning were just a fraction of the 1,000-plus in the ship’s company.

Around that time, another sailor who stopped at a sideport door in the Upper V to chat with a sentry “observed white smoke rising from the Lower V ramp into Upper V,” according to the report. One of them ran up the ramp and through the hangar to reach the quarterdeck, telling the officer-of-the-deck about the smoke.

At about 8:15 a.m. the engineering duty officer ran into a civilian contractor who told him of smoke near the mess decks. The EDO went to investigate and met another crew member who was also investigating a report of smoke.

Crew members who spoke with investigators described some confusion in communication among the watch teams as they scrambled to sort out the reports of smoke and get a solid picture and location of the growing blaze so they could organize and attack the fire. Investigators found inconsistent statements from crew members about the actions to investigate the reports of smoke and fire alarms and why there was a delayed reporting of the fire over the ship’s intercom system – the 1MC.

“Numerous sources agree to having heard a rapid ringing of a bell but disagree on whether the casualty was announced as ‘white smoke’ ‘black smoke,’ or ‘fire,’ as well as the location of the casualty: ‘Lower V,’ ‘Upper V,’ or ‘Hangar bay,’” the investigation found. “At 0820, the Petty Officer of the Watch (POOW) noted in his log: ‘Fire reported in Lower V.’”

The duty fire marshal told investigators he received a report of smoke in the Upper V and went to investigate, then called the Damage Control Central watch supervisor to tell the ship’s company about the casualty after seeing “smoke pouring out of Lower V.”

“The OOD stated that the [Damage Control] Central watchstander informed him that they already made a 1MC announcement. Having not heard any announcement, at 0820, the OOD called away the casualty over the 1MC,” the report found. The officer told investigators “he delayed calling away the casualty due to the possibility of a benign reason for the smoke (such as starting an Emergency Diesel Generator).”

That 1MC call was the first time the ship’s command duty officer, who was in his stateroom, learned of the fire. He reached the hangar, where the crew was organizing an initial suppression effort, at 8:24 a.m. The CDO had texted the ship’s commander and executive officer, who were both at their residences, about the reports of smoke. Bonhomme Richard’s commander, Capt. Gregory Thoroman, received the text about the black smoke at 8:32 a.m., shortly before the senior enlisted sailor – the command master chief – called to tell him “that a few sailors suffered smoke inhalation.” Thoroman drove to the base, as did the XO, who was told of the fire by the CMC.

At 8:22 a.m. the sound of the ship’s bell could be heard from a nearby parking lot.

Minutes later, crews aboard destroyers USS Russell (DDG-59) and USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62), which were also berthed on Pier 1, reported black smoke coming from Bonhomme Richard. Both destroyers “assembled their duty sections and began equipping Rescue and Assistance (R&A) teams,” with a team of 11 from Russell and eight from Fitzgerald reaching BHR’s hangar. But neither team was directed to join in the fire attack, according to the investigation.

the radiant fire in Upper ‘V’ at approximately 0951. US Navy Photo

At 8:25 a.m. “a ‘ship fire’ was reported on the Anti-Terrorism Tactical Watch Officer (ATTWO) Harbor Defense Net radio channel.”

“In those early minutes, the sailors had no radios so they used their own cellphones to communicate,” the lead investigator found. And the 1MC “did not work in many areas of the ship to include DC Central; and there was a lack of urgency. When initial responders from Ship’s Force descended into Lower V, no one shared the same understanding of what firefighting capability was online, contributing to their failure to apply agent to the fire or set fire boundaries, which enabled smoke and heat to intensify.”

Attack teams had trouble finding serviceable fire stations. In fact, 187 of the ship’s 216 fire stations – 87.5 percent – were in Inoperable Equipment Status condition at the time of the fire, the report said.

Smoke and Confusion

Meanwhile, the small duty force aboard Bonhomme Richard scrambled to assemble firefighting teams and to investigate the fire’s location. Despite thick, choking smoke spreading through the ship – and amid dangers from searing heat and possible fire flashes – some sailors, including several chief petty officers, didn’t don the required firefighting equipment. They mistakenly believed they couldn’t do so while wearing the Type III Navy working uniform, rather than their coveralls.

The ship’s fire teams were haphazardly outfitted and equipped, some with self-contained breathing apparatuses and firefighting ensembles, but others without one or the other, the investigation found.

Several fire teams of sailors ventured to the Upper V and found hot spots but no fire. And as sailors began to lay hoses to attack the spreading fires, they encountered fire stations with missing fire hoses and broken hose fittings.

Moreover, there were no concerted direction nor any announcements from DC Central.

“The DC Central Watch Supervisor stated that neither he nor EDO had an idea of how bad the fire was until later events forced them to evacuate DC Central. At no point did either the DC Central Watch Supervisor or EDO attempt to start any additional equipment or activate Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) firefighting systems,” investigators wrote.

“Despite the lack of reports that any of announcements were received or acted upon, neither the EDO nor DC Central Watch Supervisor sought confirmation that their announcements were broadcast,” investigators found. “Though the senior EDO in the duty section (name redacted) did not hear any 1MC announcements from DC Central, he did not proceed to DC Central to determine whether the EDO was attempting to execute control of the firefighting effort.”

Worse, the ship’s installed AFFF systems weren’t put into action “in part because maintenance was not properly performed to keep it ready and in part because the crew lacked familiarity with capability and availability,” the lead investigator wrote. Many of the ship’s hatches and doors – a critical first line of defense to isolate a fire and slow the spread – couldn’t be shut without disconnecting temporary utilities in place for the maintenance availability work.

Two crew members told Naval Criminal Investigative Service investigators that “they stated it was not possible to set boundaries in Lower V, because it was such a large space. Additionally, they reported the fire spread too fast to set effective boundaries. However, most Duty Section 6 Sailors aboard at this time stated in interviews they neither knew how to set boundaries nor operate the quick-disconnects. Limited quick-disconnect training was conducted early in the availability, but was not repeated nor reemphasized.”

At 9 a.m., two fire teams – including one from Russell – were told to evacuate the hangar because of smoke, and they watched “numerous” BHR sailors evacuate the ship.

At about 9:15 a.m., deteriorating smoke conditions in the hangar led the CDO to order all personnel without SCBAs to evacuate the ship after he had consulted with the ship’s captain. But the investigation found “there are varying reports on whether this evacuation order was communicated over the 1MC.”

Sailors searched berthing areas to evacuate any strayed crew, including one sailor who collapsed in a passageway after spending 15 minutes searching while not wearing any emergency breathing equipment. Another sailor carried her to the hangar, where she “regained consciousness” and was evacuated for smoke inhalation.

Investigators found that none of the crew evacuating the ship used an emergency egress breathing device (EEBD), which is a metal bottle of compressed air. “There are conflicting accounts as to whether all berthings had EEBDs in place,” they wrote. One sailor they interviewed looked for an EEBD, but could not find one and most of the sailors “did not try to find an EEBD or were concerned that returning to find an EEBD might have led to them becoming trapped by the fire.”

Mixup and Explosion

Thoroman, the ship’s captain, reached the base at 9:05 a.m. and met with Federal Fire and San Diego Fire chiefs at the incident command post set up on Pier 2.

The fire response already was substantial, as subsequent fire alarms broadcast calls for additional help, and the call for mutual aid prompted local fire departments to send crews to the base. But an hour into the fire, no water or retardant had been laid onto the fire, even though FedFire crews had laid down their hose line toward Lower V. The fire had spread unabated for nearly two hours before the first firefighters – crews from the San Diego Fire Department – poured water onto the flames.

That happened at 9:51 a.m. on the upper vehicle deck, where the city firefighters on their own initiative attacked a fire along the space’s starboard side. While unfamiliar with the ship’s layout, they told investigators, they nevertheless reached one area of the fire and fought the blaze for at least another 30 minutes before conditions deteriorated with the fire’s continuing multi-fingered spread.

By then, the billowing smoke had turned heavy and black. One city firefighting official told his teams: “This compartment is about to blast.”

At 10:37 a.m., the on-scene command ordered all firefighting teams to evacuate the ship.

At 10:50 a.m., “approximately 90 seconds after the last firefighters had departed the ship, a massive explosion occurred” aboard, according to the report. The ensuing shock wave knocked down people on the pier and blew debris across to Fitzgerald, and massive smoke billowed high into the clear sky across San Diego Bay. The report said that if sailors and firefighters had been aboard, several would have been killed.

The delayed firefighting response in those initial crucial minutes and hours – despite the BHR crew’s initial search and the city firefighting team’s attack – further strengthened the fire’s unchallenged spread toward 11 of the big-deck amphib’s 14 levels. Flames ignited compressed air tanks. Gases and vapors ignited super-heated fires, while air flowing in from vents and through passageways fueled the fires’ spread up and down trunks and through damaged compartments.

“This explosion occurred after more than two hours of efforts where none of the ship’s installed firefighting systems were employed and no effective action was taken by any organization involved to limit the spread of the smoke and fires,” the lead investigator wrote in the executive summary. When the ship was evacuated, “without personnel onboard, available installed systems, or electrical power, the fires on Bonhomme Richard were unimpeded.”

“Subsequent attempts to regain a foothold aboard relied on ad hoc strategies, delivering too little firefighting agent to combat the pace of the fire’s spread. Throughout the first day of efforts, agent was never applied to the seat of the fire, and the opportunity to do so was lost once the fire spread beyond the perimeter of Lower V and across the entire ship.”

Bureaucratic Fires

Bureaucratic divisions hampered firefighting efforts, the investigation found.

On that first day, BHR’s fire teams of sailors didn’t integrate with FedFire crews. Ships around the waterfront began sending teams of sailors to help fight the fire, but the effort “was unorganized” initially before a coordinated watchbill was established. For five days, the ship and FedFire worked from separate command posts on Pier 2, without clear indications to others as to who was in charge of the firefighting mission.

After San Diego Fire’s initial response and fire attack, fire crews did not reenter the ship after it was evacuated. SDFD officials said they would support from the pier but not reenter the ship, citing their manual that reads: “‘[a]ctivities that pose a significant risk to firefighters shall only be taken when there is potential to save lives.'”

But it prompted frustration and disagreements with FedFire and the Navy over the city department’s safety policies, investigators noted. After discussing it with the Expeditionary Strike Group 3 commander, the FedFire chief said he told the SDFD chiefs to leave “if they were not going to provide meaningful assistance to fight the fire.”

The noticeable departure of SDFD crews and vehicles was followed by that of other localities who had responded to the mutual aid call in the large-scale, regional fire response, further dampening the mood on the waterfront amid the growing emergency in front of them.

“Uncertainty over whether SDFD was specifically released or left on their own led to confusion and disappointment among Bonhomme Richard leadership when municipal firefighting units began departing,” the investigator wrote.

With the afternoon arrival of other ships’ fire teams to assist, more sailors joined FedFire in chasing down the fire as it spread that afternoon. At 6:30 p.m., the fire “was burning throughout the entire length of the ship with approximately three decks on fire to include equipment on the Flight Deck and the ship’s superstructure,” according to the report.

At 6:55 p.m. a second explosion jolted the ship, caused “multiple minor concussive and blast-type injuries,” and prompted a second evacuation that halted firefighting efforts for several hours, the investigation states.

It “originated from an 8-inch Fuel, Jet Propulsion (JP-5) fuel pipe located in an auxiliaries division compartment underneath the Upper V ramp on the port side of the ship, Valve Grinding Area (3-81-2-Q),” investigators found. “This explosion blew a watertight door from an adjacent compartment, Engine Test Area (3-82-2-Q), across to the starboard side of Upper V and resulted in a large fireball.”

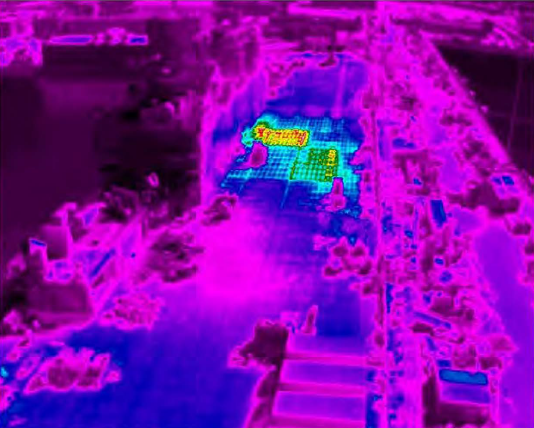

With the fire’s continuous spread, the Navy’s top concerns were the failing integrity of the ship’s superstructure, a warping flight deck and collapse of the cavernous hangar bay. That evening, in an agreement between the Navy Southwest Regional commander and the San Diego mayor, SDFD helicopters flew a mission to assess the fire’s impacts, and thermal imaging showed 1,200-degree fires burning on the superstructure. A few hours later, the first two Navy Seahawks began dropping saltwater onto the ship in an aerial fire attack that totaled 1,649 water drops over four days.

By day two, the fire remained out of control in the ship’s interior spaces as firefighting efforts expanded, with a drone equipped with thermal imaging helping to identify hot spots. By the third day, holes were cut into those spaces to enable the deployment of AFFF, and high-intensity fire pumping equipment shot seawater onto the flight deck and superstructure.

Communication problems between BHR and FedFire continued to hamper the firefighting response, the report found, as crews battled stubborn fires in the disbursing office, high heat delayed teams reaching the joint intelligence center, and fire in a debris-filled troop washroom kept reigniting.

Meanwhile, all that water pouring into the ship required a massive dewatering effort to offset the shift and list of the ship driven by compartments filled with water.

But at 10:30 p.m. on July 15, firefighting waters that accumulated in the O1- and O2 levels shifted so significantly that the ship “experienced a rapid shift from 2.1-degree starboard list to a 4.9-degree port list,” according to the report. That happened over a 90-second period. Firefighting teams aboard at the time were evacuated and firefighting efforts were halted for nearly two hours.

The next afternoon, on July 16, the ESG-3 commander declared the fire was finally out.

“The overall command and control for the fire response was initially chaotic, but it improved over time through ad hoc decisions and assignments,” the investigator wrote.

“Although the CO, XO, CMC, [Chief Engineer], and DCA were all present on the pier prior to the explosion,” the investigator continued, “they failed to establish command and control of the situation and did not lead action to integrate fire response efforts.

“Instead, Commander, Expeditionary Strike Group THREE (ESG-3), the ship’s operational commander who has no assigned role or responsibility in response to a shipboard fire during a maintenance availability, stepped into a command and control vacuum to align the various ship, installation, and external organizations by employing a make-shift emergency response organizational structure.”

After an evaluation of what it would cost to repair the ship, the Navy decided to instead scrap Bonhomme Richard.

In April, the ship was towed from Pier 2, through the Panama Canal to Texas, where International Shipbreaking LTD., took possession of the remains of the ship for $3.66 million.

Miami Connection

In 2012, the Navy lost Los Angeles-class submarine USS Miami (SSN-755) to arson while the ship was undergoing an availability at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Maine when a shipyard worker set a fire aboard the boat.

The subsequent fire resulted in an uncontrolled blaze that cut the life of the submarine short after the Navy determined it would take $750 million to repair.

As a result of the fire, Naval Sea Systems Command crafted a new set of procedures to prevent fires when ships were in maintenance – NAVSEA Technical Publication, Industrial Ship Safety Manual for Fire Prevention and Response, known as the 8010 manual.

“In response to this fire, Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command (USFF) convened a Fire Review Panel to determine how MIAMI could be lost in a shipyard environment despite readily available fire prevention programs and resources,” according to the Bonhomme Richard fire investigation.

“The critical takeaway from the Miami investigation, as stated in the USFF endorsement was that ‘accept[ing] a reduced margin to fire safety when a ship enters an industrial environment’ was a key driver to the policies and procedures that developed to prevent a similar outcome.”

While the 8010 manual set up procedures to prevent another fire like the one that destroyed Miami, investigators found that the Navy did not follow the rules outlined in the document.

“In the last 5 years, policy changes and corrective actions to address fire safety were inconsistently implemented or failed to be implemented across the Navy maintenance organization… training, implementation, and compliance with the 8010 Manual in private shipyards was not representative of maintenance on nuclear vessels being executed in the public yards. Additionally, there was a lack of procedural compliance and effective oversight within the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), Navy Installations Command, and Naval Surface Force Pacific Fleet,” Conn wrote.

Investigators found that most sailors aboard Bonhomme Richard were not familiar with the updates to the 8010 manual.

“These personnel had a general unfamiliarity with the content of the 8010 Manual and commented that their training had not prepared them to combat a fire of the magnitude having occurred aboard Bonhomme Richard,” according to the report.

In a subsequent opinion, Conn said, “[t]he considerable similarities between the fire on USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) and the USS Miami (SSN-755) fire of eight years prior are not the result of the wrong lessons being identified in 2012, it is the result of failing to rigorously implement the policy changes designed to preclude recurrence.”