The Navy’s surface fleet has a new set of orders that updates a sleep policy to give sailors on watch rotations a bit more sleep and create a culture supporting a more ready, rested and focused seagoing force.

The “Comprehensive Crew Endurance Management Policy,” signed off Dec. 11 by Naval Surface Force Pacific and Naval Surface Force Atlantic, is the first update to the joint instruction issued just months after two 2017 fatal at-sea collisions rocked the Navy.

The latest directive takes aim at tackling the problem of fatigued watchstanders in an often-sleep-deprived force. The Navy wants ship crews to be operationally ready by getting more restful sleep, staying physically active and eating nutritiously – all part of the concept of “crew endurance” that officials believe will lead to safer operations and reduce risks of errors or mishaps.

“This is not a sleep instruction. This is an endurance instruction,” said retired Capt. John Cordle, a former ship commander who retired in 2013 and last summer took the job of human factors engineer, a new position at SURFLANT’s safety department in Norfolk, Va. Cordle, along with his counterpart at SURFPAC, helped lead the update to the 2017 instruction.

“We took a look at the instruction as it was. We took a look at what we’ve learned in the last three years. We reached out to the experts,” including the Crew Endurance team at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., and the Naval Health Research Center in San Diego, as well as the National Transportation Safety Board and National Institute of Health, Cordle told USNI News. “How can we make this instruction better, using science and research that we’ve done (and) what we’ve learned in three years? So that was the genesis of the rewrite.”

The underlying premise of the 2017 instruction, issued by then-SURFOR Vice Adm. Tom Rowden, hasn’t changed significantly. The goal remains the management of healthier, less fatigued crews. The revised policy takes a more holistic view to tackle fatigue and incorporates NPS’s “Crew Endurance Best Practices” on napping, sleep hygiene, physical activity and nutrition. But it also reinforces individual responsibility.

“It is the responsibility of every sailor to take advantage of sleep opportunities. Sailors who are provided with protected sleep periods but deliberately use them for other purposes are subjecting themselves, their shipmates and their ship to unnecessary risks,” the instruction states. And “COs and commanders will ensure that all personnel are trained on the facets of crew endurance, especially the overall risk that fatigue presents to the ship, their crewmates and themselves.”

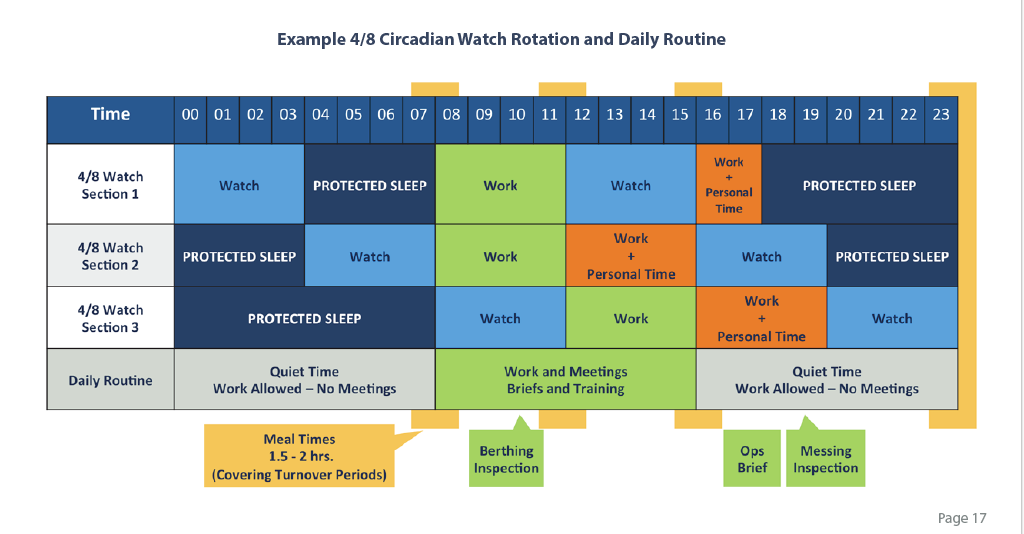

It directs that commanders should establish watch rotations schedules that implement that natural sleep-awake concept as well as “a supporting schedule to make sure that folks have an opportunity to sleep,” Cordle said.

It also emphasizes a renewed risk-management matrix for commands crafting watch bills based on the 24-hour internal “circadian” clock. The matrix weighs each watchstander’s watch-to-rest ratio, experience, crew coherence and equipment to determine risks and mitigation, such as swapping out an inexperienced sailor or providing for additional sleep or supervision.

But how much sleep is required?

The 2017 instruction called for a minimum of seven hours of sleep – split into a five-hour sleep and two-hour nap – in a 24-hour day “under ordinary circumstances underway.” That guideline is in line with minimum seven to eight hours of daily sleep the NTSB identifies as important to reduce fatigue and ensure alertness.

But in reality, few sailors get seven uninterrupted hours of actual sleep, Cordle noted. So the new policy slightly bumps up that minimum. “Sailors must be given the opportunity to obtain a minimum of 7.5 hours of sleep per 24-hour day,” with an uninterrupted 7.5-hours or an uninterrupted 6-hour sleep period and uninterrupted 1.5-hour restorative nap, states the instruction, COMNAVSURFPACINST/COMNAVSURFLANTINST 3120.2A.

The expanded guidelines amplify fatigue’s impacts on a crew’s effectiveness, noting that sleep-deprived watchstanders are less effective, have slower reaction times and may struggle with making good decisions, and warning against a sailor’s workday that stretches beyond 12 hours. “Twelve hours is a long day,” said Cordle. “After 18 hours, you start to degrade.”

Preventative measures

The fatal 2017 collisions involving destroyers USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and USS John McCain (DDG-56) prompted sharp criticisms and scrutiny over the Navy’s management, maintenance and training of its surface fleet and personnel. In the fallout came renewed attention to manning, training and operations, and with it a spotlight on a sleepy, fatigued force.

Those collisions weren’t the first ones caused by fatigue and lack of sleep among watchstanders. The skipper involved in the 2009 grounding of USS Port Royal (CG-73) off Hawaii reported little sleep in the days prior, for example. Fatigue and a lack of sleep are problems long identified across the military services. Sleep remains a much-studied field of science and health, including an ongoing NPS study that’s looking closely at a ship’s engineering department.

As a former ship skipper, Cordle has had first-hand experiences in the importance – and cost – of sleep at sea. In a February 2019 article in Proceedings – “Captain, Get Some Sleep!” – he recounted his own failing when, as skipper of destroyer USS Austin (DDG-79), his fatigue led to a mishap that injured one of six crew members who were tossed into the sea from their rigid-hull inflatable boat.

He’s been an advocate for measures that promote new attitudes about sleep and its importance in overall health and readiness. In an article in the January 2020 issue of Proceedings, he wrote that “fatigue is the Navy’s black lung disease” and warned that failing to take corrective actions now would be to the detriment of sailors’ long-term health.

“I really do see kind of a culture change. Certainly not all the way there yet, but there was a time … when being tired was sort of the measure of something to be proud of,” he told USNI News. “You’d hear people say, well I was up for 36 hours. Oh yeah? I was up for 40 hours. At the time, that would be something to congratulate somebody. Now, that’s something to say, well you idiot, that’s stupid, right?”

Nowadays, naps “are kind of part of the culture,” Cordle said, although he acknowledged “a cultural resistance to maybe admitting that we’re taking naps.”

“We have science to show that that’s not the way to do business,” he said. “At the end of the day, that warship is out there to be ready when missiles come inbound, when you hit something, when something bad happens (and) you have to respond.”

“You go into battle with the sleep you have,” he added, “and whether you got that in an eight-hour stint or by taking a nap, if it keeps you alert on watch, then it’s worth it.”

Guidelines

In his job, Cordle regularly talks to ship skippers and visits with crews. “My feedback from this ships is they are implementing this,” he said, adding, “it’s more than just a watch bill. It’s the whole mindset of the prioritization of sleep and watching for fatigue.”

But while the instruction challenges COs to review schedules for meals, meetings and training events so those don’t cut into sailors’ sleep times – especially that of watchstanders – it doesn’t mandate specific schedules or actions.

“One of the things we didn’t want to do was tell commanders, ‘you shall use this watch rotation,’ ‘and people will sleep at this time,’” he said. “It’s all the broad guidelines to make sure they get enough sleep, to make sure that’s part of the planning process.”

“It makes no sense to make it a requirement if I know you can’t always meet it,” he added.

Cordle expects to see secondary benefits of more sleep and circadian watch bills benefit the fleet. One captain, he said, called it “life-changing.”

“Watch teams become coherent teams, and they start to compete with each other, and they start to workout together. They start to study together,” he said. “So when you sleep better, you learn better and you qualify better. You have more time to workout. … You can study better for your qualifications.”