ABOARD USS GRAVELY, IN THE BALTIC SEA – A year and a half after surface navy leadership demanded ships implement new work schedules to ensure sailors got enough sleep, officers aboard a destroyer say the new scheduling has made them more effective at sea and they’re not looking back.

Among the findings in deep-dive looks at the surface navy following two fatal collisions in 2017 was the fact that many officers were standing watch during pivotal evolutions – refuelings at sea (RAS), strait transits, pulling into port – on little or no sleep. With the medical community firmly stating that being sleep-deprived can impact alertness and performance in ways similar to drinking alcohol, the Navy ordered in late 2017 that all surface ships create a watch standing schedule that allowed sailors to sleep at the same time every night with seven hours of uninterrupted sleep.

Lt. Josh Womack, the combat systems officer and the senior watch officer on guided-missile destroyer USS Gravely (DDG-107), joined the ship’s crew in October 2017, just before the switch to the circadian rhythm scheduling in January 2018.

“We would sound reveille at 5:30 in the morning, and every day that reveille would start with a song on the 1MC, so even if for whatever reason you could sleep in, everyone on the ship was awake after the song blared on the 1MC. First meeting of the day would start at 6:30, with the (executive officer) call for department heads, and then quarters at 0700,” he told USNI News while aboard the ship during the BALTOPS 2019 exercise last month.

“And then you’d work the full day, just like you normally would, and meetings would often go well into the night, sometimes 2000 or 2100. You would stand watch throughout that time; sometimes you would have a night watch, so you would work the full work day and then have watch from 2100 to midnight or midnight to 0300. So very very possible that you could have a full work day with two to three hours of sleep, and that was kind of accepted as the norm.”

Womack said it was hard to stay focused on so little sleep, but it was “almost a point of pride to be able to go two or three days straight with two hours of sleep.”

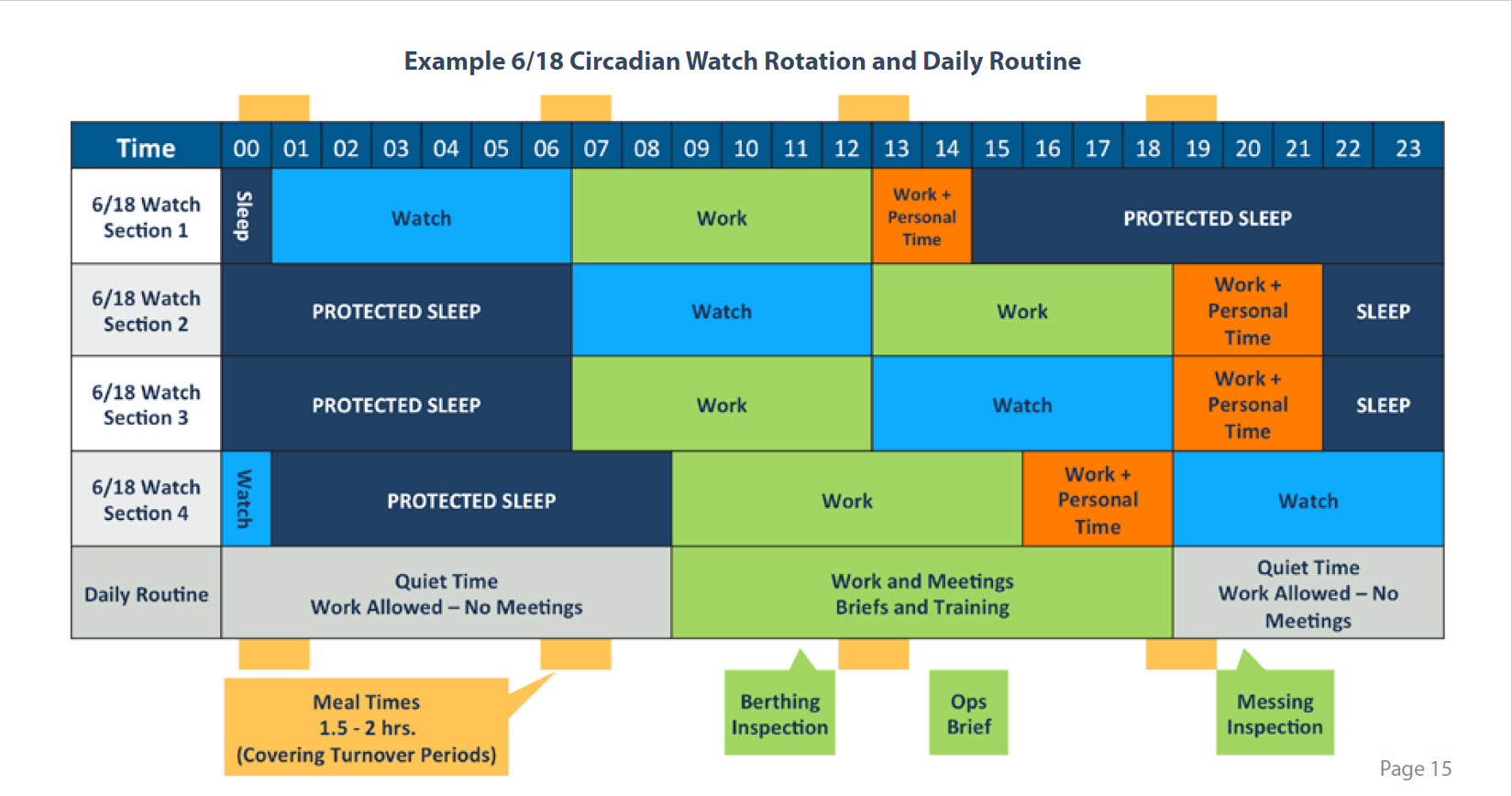

He said the transition was pretty smooth, with the Navy providing notional watch schedules based on the number of watches the ship had been using before. Gravely had been working with four watch teams, who stood three-hour watches twice a day each.

Meal hours were shifted 30 minutes ahead or back to ensure that everyone could get a meal before or after their watch, which was a top priority, but the main concern was whether all the meetings could be crammed into the workday – which was much shorter under this new scheduling model.

Today, Womack said, “work day does not begin before 0900, and that includes passing word on the 1MC – so no reveille, no breakfast. We do pass some, but we try to minimize to just be critical announcements. … Work day starts at 0900. For department heads, we’ll have a meeting with XO at 8:30, a half hour prior, but nothing else prior to that point. And then meetings will be during the work day, from 0900 to 1600. And then we have a final brief at the end of the day, 1600 to 1630, and then dinner. And from dinner until the next morning, 0900, we refer to it as protected sleep hours, protected hours, and we really do a pretty good job adhering to that. Occasionally the schedule will require us to have a couple meetings or boards after dinner, but it really is just occasional that it happens, and it’s specific to leadership; we do a pretty good job of making sure that the junior sailors will always get time off.”

For Executive Officer Cmdr. Corey Odom, who checked into the ship this spring, finding time for all the meetings was his main concern. Odom spent 10 years in the submarine community as an enlisted sailor, where he worked six hours on and 12 hours off. After becoming a surface warfare officer, he served as weapons officer and later combat systems officer on destroyer USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79), where meeting after meeting after meeting drove the daily schedule.

“You have to plan better” with a shorter workday, Odom said.

“I don’t think any of the meetings changed, but you have to be more efficient. … You could have PB4T, which is Planning Board for Training – some ships could last an hour and a half, some ships an hour. But if it’s effective and efficient, it’s 30 minutes. You know that you have a finite amount of time to do briefs, so it has to be efficient. So it means a little bit more work prior to the meeting,” he said, but with that efficiency “you gain back time in your day.”

“At one point you thought you were trying to cram 12 hours of meetings into 13 hours of space,” he said of his time on Oscar Austin. “But when you’re efficient, you’re really cramming six hours of meetings into 12 hours of space.”

Odom said he learned during his XO training at the Naval War College in Rhode Island that the submarine community had also switched over, which surprised him after so many years of 18-hour days. But he said he’s glad the Navy is embracing this, which allows people to sleep at the same time each night and to get enough sleep for their bodies and minds to function properly.

“At the time, as you live through it, I think it just seems normal. This is part of our culture, to do more with less, and including sleep. … We were always safe, but, you know, when you looked at it, you thought, well maybe my thought process was a little slow on a couple things,” he said.

Since joining the Gravely crew, though, “every decision we make now, how much rest does the crew have is something that’s discussed. … I can tell you, several briefs since I’ve been here, the captain has let it be known that, if you have a sailor that is on the morning RAS (tomorrow) and is on the watch tonight, you need to make plans to make sure that sailor gets the proper rest.”

For Womack, who oversees the watch scheduling and ensuring that all watch standers are properly rested, he said there have been a few instances of having to find a replacement watch stander due to someone not having gotten enough sleep for whatever reason, but he said the ship has enough certified watch standers that that hasn’t’ been a problem.

He said Gravely has spent most of its time at sea since January 2018, participating in overseas exercises and helping other strike groups and amphibious ready groups train for their deployment, and now as the flagship of Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 in Europe. That time at sea has allowed the crew to really embrace the circadian rhythm scheduling, and with the ship coming back home soon, Womack said they’re trying to figure out an in-port schedule that will make crew members equally happy.

“Being underway, in my opinion, is easier than being in port with the work hours,” he said.

“Even standing six hours of watch a day, you feel more rested at sea than you do in port. And I think that’s the general consensus across the board.”