This post is part of a series of stories looking back at the top naval news from 2020.

Like the U.S., international navies grappled with not only the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic but regional security concerns from China’s naval expansion and operations in the Pacific to Iranian and Russian operations in the Middle East.

Russia on the Move

2020 marked an active period for the Russian Navy, as it supported its presence in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea in particular.

In early 2020, the Russian surveillance ship Viktor Leonov was operating off the East Coast of the United States. During its regular patrol, the ship was cited by the U.S. Coast Guard for unsafe operations near civilian maritime traffic.

“The United States Coast Guard has received reports indicating that the RFN Viktor Leonov (AGI-175) has been operating in an unsafe manner off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia,” read the notice from Coast Guard in Charleston, S.C.

“This unsafe operation includes not energizing running lights while in reduced visibility conditions, not responding to hails by commercial vessels attempting to coordinate safe passage and other erratic movements.”

In May, the Russians promised a naval build-up in the Mediterranean, reported TASS.

Then, in July, USNI News and Naval News reported Russian submarines based in the Black Sea were conducting combat patrols in the Mediterranean, in apparent violation of the Montreux Convention. The improved Kilo-class boats are armed with Kalibir land-attack missiles that could support operations in Syria from the Eastern Mediterranean.

“A Kilo-class submarine can go anywhere in European waters and strike any European or North African capitol from under the waves. You don’t see it coming,” then-Commander of U.S. Naval Forces in Europe and Africa Adm. James Foggo said in June.

Russian ships have also been seen escorting Iranian tankers to Syria, USNI News reported in October.

Russia’s Arctic submarine force has increased in importance in the overall structure of the military. In June, President Vladimir Putin announced that the Northern Fleet would be declared its own military district, elevating its importance in the Russian military structure.

Northern Fleet commander Vice Adm. Aleksandr Moiseyev told a Russian military newspaper the prime focus for the command would be to prepare for a major strategic exercise in September called Zapad-2021, reported The Barents Observer.

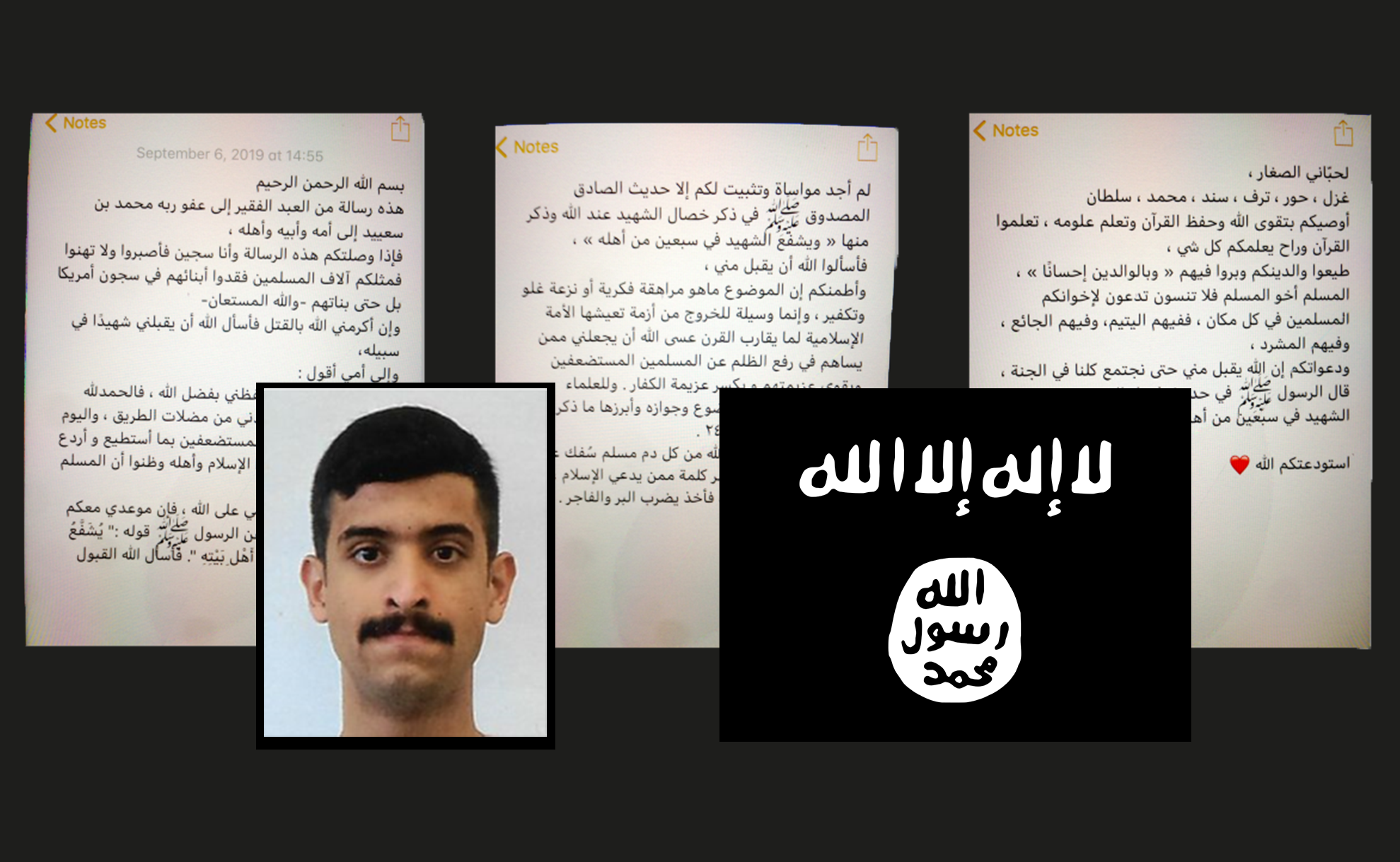

Pensacola Shooting Fallout

The December 2019 fatal shooting of three U.S. sailors by Royal Saudi Air Force 2nd Lt. Ahmed Mohammed Alshamrani resulted in subsequent investigations into how the Pentagon trains foreign military students.

More than 5,100 foreign military students from 153 countries train in the U.S. as part of arms sales agreements or are students at the U.S. military’s undergraduate and graduate-level colleges, according to the U.S. State Department.

In January, the U.S. expelled 21 Saudi military students.

“Of the 21 Saudi military members returning to Saudi Arabia, 17 military members had either jihadi or anti-American content in their social media accounts,” reported USNI News. “Fifteen individuals, including several of the military members with jihadi or anti-American content, possessed child pornography images.”

The fallout raised questions on the efficacy of the vetting process for foreign military students and prompted restrictions on personal firearms for visiting students.

Iranian Misfires

In January, Iranian forces shot down a Ukrainian passenger plane, killing 176 people aboard, after air defense crews mistook it for a military aircraft.

“Preliminary conclusions of internal investigation by Armed Forces: Human error at time of crisis caused by US adventurism led to disaster,” Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif tweeted at the time, reported CNN.

The shootdown of the civilian airliner came hours after the Iranian military fired missiles at U.S forces at the Bagdad airport in retaliation for a targeted strike that killed former Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani.

Later in May, 19 Iranian sailors were killed in a friendly fire incident during a naval exercise in the Gulf of Oman.

Iranian frigate Jamaran fired an anti-ship missile into the support vessel Konarak, which had laid targets for the frigate.

“On Sunday evening… during naval exercises performed by a number of the naval force’s vessels in the waters of Jask and Chabahar, an accident happened involving the Konarak light support ship vessel, causing the martyrdom of a number of brave members of the naval forces,” read an Iranian navy statement.

In May, the U.S. issued a warning to Iranian ships after an incident in which about a dozen Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy after “repeatedly conducted dangerous and harassing approaches of the USS Lewis B. Puller (ESB-3), USS Paul Hamilton (DDG-60), USS Firebolt (PC-10), USS Sirocco (PC-6), USCGC Wrangell (WPB-1332) and USCGC Maui (WPB-1304),” the Navy said at the time.

The IRGC also continued to operate a suspected surveillance and forward-operating ship in the Red Sea, USNI News reported in October. In November, the IRGC inducted a new special operations support ship

“Shahid Roudaki is being described as an Intelligence and Support Ship by Iranian media. The U.S. Navy equivalent is something between a special warfare support vessel and an Expeditionary Mobile Base (ESB),” reported USNI News at the time.

Not-So-Crude Seizure

In August, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it had raided four Iranian tankers, seizing 1.1 million barrels of petroleum products that were bound for Venezuela.

The seizure of the petroleum led the Iranians to search tankers in the Gulf of Oman in search of the taken cargo.

Flying from an Iranian Navy SH-3 Sea King, an Iranian special operations team fast roped aboard the deck of M/T Wila off the coast of the United Arab Emirates and held the tanker for five hours before leaving. He next day, the DoJ announced the seizure of the petroleum products.

“They were looking for their gas,” DoJ spokesman Marc Raimondi told USNI News in August.

Ahead of the announcement, the U.S. contracted merchant tankers to transfer the oil at sea away from the ships that were transporting the illicit cargo.

According to a report in The Wall Street Journal, “the owners of ships targeted by the U.S. legal action—the Luna, the Pandi, the Bella and the Bering—then agreed to transfer their cargo to vessels owned by Greece’s Eurotankers and Denmark’s Maersk Tankers A/S, which were then bound for Houston.”

Bok Choy and Sovereignty in the South China Sea

The Chinese government continued to make incremental steps to cement control of its holdings in the South China Sea by expanding its military footprint in man-made islands in the region. Beijing continued to tease creating a so-called air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea.

In June, officials in Taiwan warned that the creation of an ADIZ would require all flights in the zone to identify themselves to the Chinese military. Given the far-flung holdings in the Spratly Islands far to the south of the Chinese mainland, it would be difficult to enforce with the current Chinese bases in the region, but an expansion of air bases would better enforce an ADIZ.

Further north in the Paracels, China is trying to solidify its claims by creating an agricultural claim to its holdings. A People’s Liberation Army Navy experiment grew 1,653 pounds of bok choy cabbage, lettuce and baby Chinese cabbage in the sand. Creating an agricultural system for the islands is yet another step toward legitimacy of the disputed claims.

“The naming of features, the growing of crops, you know, it’s all a stamp of sovereignty,” retired Indian Navy Capt. Sarabjeet Parmar, the executive director of the New Delhi-based National Maritime Foundation, said in June.

“And over a period of time, when it becomes a normal accepted custom, the strength of maybe China’s argument, or the backbone of China’s argument, will get strengthened.”

Chinese maritime forces were active in the South China Sea as part of its ongoing campaign to assert regional dominance.

In April, a China Coast Guard cutter rammed a Vietnamese fishing vessel, while a Chinese survey ship operated in what the U.S. State Department called a “bullying” fashion toward a Malaysian oil exploration survey for almost six months.

In response to Beijing’s naval expansion, Taiwan is retooling its own military to face “a more belligerent and aggressive” China, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen said in August. Taipei is purchasing anti-ship missiles and unmanned aerial vehicles from the U.S. to counter Chinese development of its amphibious forces.

The Philippines Changes Course on Visiting Forces Agreement

The Philippine government reversed course on an agreement to let U.S. forces operate from bases in the country. In February, President Rodrigo Duterte decided Manilla would withdraw from the 1998 agreement that set conditions for U.S. military and Coast Guard personnel and equipment entering the Philippines.

“The agreement also sets the jurisdiction and procedures in regard to any U.S. military and civilian personnel committing a crime in the Philippines, as well as visa and passport requirements,” reported USNI News at the time.

The pullout was in reaction to U.S. denial of a visa to a Duterte political ally and was made in some haste, according to press reports.

“Duterte often responds forcefully to things, and this was a forceful response. Whether it represents a strategic shift, I think we’re seeing the Philippines say ‘let’s wait a minute, let’s think about this and see if that really is a strategic benefit for us to end the Visiting Forces Agreement,” John Schaus, a fellow with the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told USNI News in June.

The later reversal of Duterte’s decision was seen largely as a hedge against the growing Chinese pressure on the Philippines in the South China Sea.

NATO Frigates in Norfolk

French anti-submarine frigate FS Normandie (D651), Canadian Halifax-class frigate HMCS Ville de Quebec (FFH 332) and Royal Danish Navy frigate Iver Huitfeldt (F361)

USNI News Photos

In January, three NATO frigates arrived at Naval Station Norfolk, Va., ahead of the deployment of the Eisenhower Carrier Strike Group.

French anti-submarine frigate FS Normandie (D651), Royal Danish Navy frigate Iver Huitfeldt (F361) and Canadian Halifax-class frigate HMCS Ville de Quebec (FFH 332) participated in a series of anti-submarine exercises with the strike group.

At the conclusion of the exercise, Iver Huitfeldt deployed with USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) as part of the strike group.

Royal Navy Carrier Strike Group

2020 marked the return of a U.K. Royal Navy carrier strike group operating at sea for the first time in decades.

The group was the largest fielded by a European country in more than 40 years, according to the Royal Navy. U.K., Dutch and American escorts assembled around HMS Queen Elizabeth (R08) for drills in European waters ahead of a deployment in the spring.

“Carrier strike offers Britain choice and flexibility on the global stage; it reassures our friends and allies and presents a powerful deterrent to would-be adversaries,” Commodore Steve Moorhouse, commander of the U.K. Carrier Strike Group, said in a statement.

The Queen Elizabeth strike group, which is set to go on its first deployment next year, embarked with 15 F-35B Lighting II Joint Strike Fighters – 10 from the “Wake Island Avengers” of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 211 and five from the Royal Air Force’s 617 Squadron “The Dambusters.” The Marine squadron will deploy with the group next year.

The Queen Elizabeth strike group included:

Destroyer

- HMS Diamond (D34) homeported in Portsmouth, U.K.

- HMS Defender (D36) homeported in Portsmouth, U.K.

- USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) homeported in Mayport, Fla.

Frigates

- HMS Northumberland (F238) homeported in Devenport, U.K.

- HMS Kent (F78) homeported in Portsmouth, U.K.

- HNLMS Evertsen (F805) homeported in Del Helder, Netherlands.

Auxiliaries

- RFA Tideforce (A139)

- RFA Fort Victoria (A387)