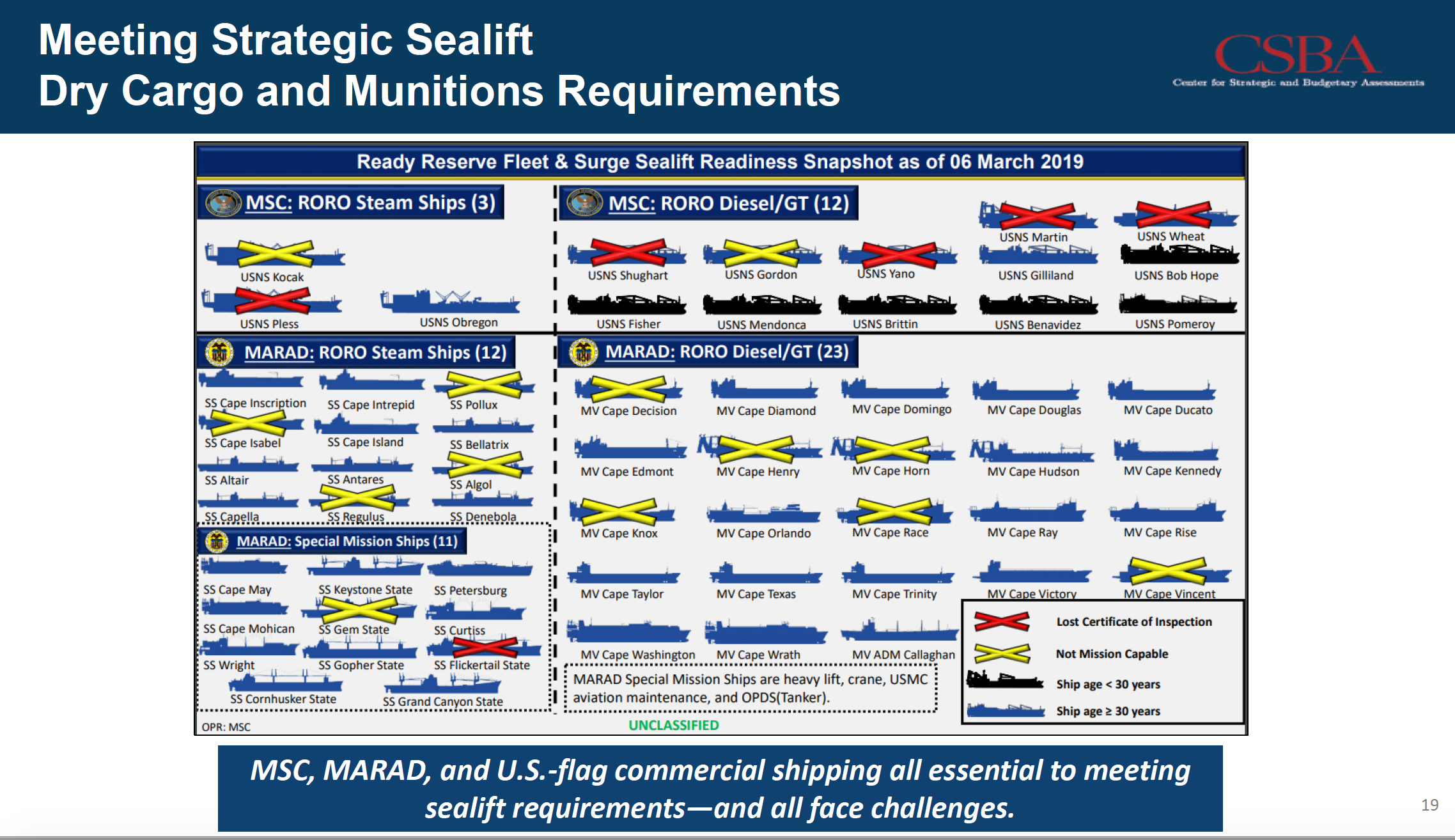

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Navy is struggling to find support to buy new logistics ships, even as a new study finds the Navy’s current plans to recapitalize that logistics fleet are insufficient to support distributed operations in a high-end fight against China or Russia.

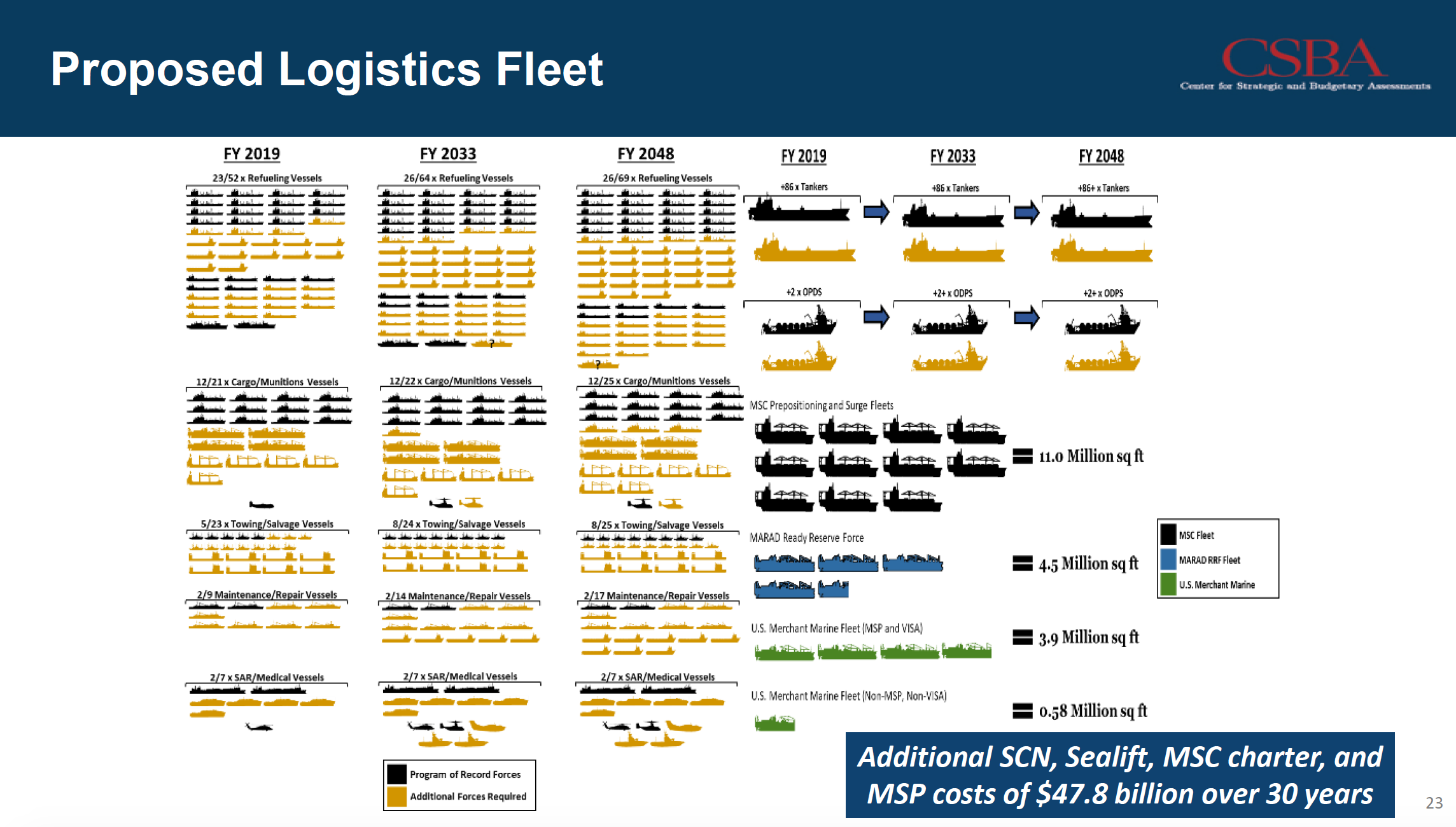

A new study by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments finds that the Navy needs to spend $47.8 billion over the next 30 years beyond what it has currently laid into its plans in order to build a logistics fleet that could refuel and resupply the Navy and Marine Corps in a fight. The study notes that, while the Navy’s current plans could support the fleet into the future in a peacetime environment, the Navy may need nearly 100 additional logistics ships of various types if it wants to win a fight against China in particular.

Today’s “logistics system is optimized for the sorts of operations that we have been having over the past 20 or so years, and it has become very efficient. However, if we … look towards moving towards great power competition with China or Russia as the adversary, who could project threats to that logistics force further back in the chain, the way we think about this problem changes dramatically,” Harrison Schramm, a co-author of the “Sustaining the Fight: Resilient Maritime Logistics for a New Era” study, said at an event today.

“The Navy currently has a hub-and-spoke model that’s highly efficient, but it’s subject to adversary interdiction of those forward bases. Additionally, because it’s been so efficient, the Navy has reduced its stocks of onboard spares aboard ships and to some degree eliminated intermediate-level maintenance of aircraft aboard carriers and other ships. It’s been an efficient model that saves funds, but it’s unsuitable for conflict against China or Russia,” co-author Tim Walton said at the event.

Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer spoke at the event and called logistics “an absolutely critical issue” for the Navy today, but he also noted the difficulty in making a business case for it. The Navy is currently working off a three-pronged plan from Congress: extending the service lives of some logistics and support ships, buying used ships to replace some of the very oldest ones, and then building some new ships under the Common Hull Auxiliary Multi-Mission Platform (CHAMP) program. Though Naval Sea Systems Command is moving out on industry engagement to inform the CHAMP program, Spencer’s comments reflect an uncertain future for the shipbuilding program despite the chief of naval operations calling for CHAMP to be procured by 2023 or sooner.

“Putting my business hat on for the business case, I can’t afford a lot of $600-million ships. I can’t really afford a lot of $400-million ships, when I can go out and buy used [roll-on/roll-off ships] for $35 to $40 million. I’m up on the Hill asking to get a little more relief – I said, I don’t want to abandon shipbuilding, please don’t get me wrong, but I need a quick little shot in the arm on the ability to rebuff and rebuild … my ability to deliver on the high seas,” Spencer said at the CSBA event today.

He did not take questions from the audience or press and did not follow up on what balance of new shipbuilding versus buying used he is advocating to lawmakers. Throughout his remarks, though, Spencer noted the tension between getting more ships for the dollar buying used versus the industrial base benefits and the long-term usage of building new ships.

“I am responsible for keeping the health of an industry; that certainly doesn’t mean my checkbook is wide open indiscriminately. We have to make every dollar count, and we have to work on this situation,” he said.

“I totally get it, buying a used ship does not promote shipbuilding community. I need to balance new and the ability to have the [total fleet support] requirement fulfilled.”

Spencer said he was on Capitol Hill this week and that logistics came up in two of his seven office visits. While speaking with one senator who was particularly interested in recapitalizing the logistics fleet, “the first point she said is, ‘but you are not funded for it, Mr. Secretary.’ And I said, ‘you’re exactly right, Senator, and we have to get after this.’”

The secretary said the Navy has not properly funded its fleet logistics and sealift ships in the past because they fall lower on the list of priorities, but he said the Navy needs to do better now and that he hoped the CSBA study would have a forcing function to make the Navy and lawmakers figure out a good path forward.

CSBA Recommendations

During the event, Schramm, one of the co-authors, noted multiple times that China’s ongoing behavior totally changes how the U.S. Navy should look at sustaining its forces in a conflict. Not only is China investing in weapons and cyber tools to go after the logistics footprint, it is also dominating the global shipbuilding, ship driving and ship husbandry industries. The Navy cannot rely upon the global market for tankers, heavylift ships and other niche capabilities the way it previously has, he said, because few or none may be available in a war against China that other nations’ mariners may not want to get involved in.

Walton, a co-author, highlighted several of the study’s recommendations during the event.

On the fuel side, the study notes the need to diversify how the Navy delivers fuel to its ships. The service should invest in large consolidated logistics tankers (T-AOTs) that could act as forward gas stations for the fleet oilers, allowing them to stay in theater instead of retreating to a port to fill back up. The study recommends accelerating the acquisition profile of the John Lewis-class fleet oilers (T-AO-205), moving to a two-a-year procurement instead of the current one-a-year plan, which would not only speed up the timeline of growing the Navy’s refueling capacity but also reduce cost from about $550 million per hull to about $500 million per hull, Walton said. The study recommends investing in light oilers (T-AOLs), akin to an offshore support vessel, that would be smaller than the fleet oilers and ideally suited to refuel a small surface action group or medium and large unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). These smaller oilers could be pushed further into contested waters because of their lower cost, Walton added. And finally, the study recommends investing in fuel bladders and unmanned or minimally manned barges as attritable assets to use in a highly contested environment.

On the munitions side, the study recommends the Navy first look at reducing its munitions logistics footprint by developing non-kinetic and energy weapons with no logistics tail or quad-pack missiles with a smaller logistics tail. It also recommends investments in the Large USV, which could serve as an unmanned magazine ship and shuttle back and forth between supply ships and warships as needed. The report also recommends buying large T-AKER vessels that would allow for at-sea transfer of cargo and munitions to smaller supply ships. And the study recommends buying a T-AKM missile rearmament ship to allow at-sea vertical launch system (VLS) rearming.

“The capability to conduct VLS rearming at sea would transform the Navy’s primary magazine, the VLS, and the Navy’s ability to reload it from a few fixed locations to many mobile ones,” Walton said.

“This would decrease fleet risk, increase fleet operational tempo and increase the efficient use of high-value or scarce munitions.”

Walton said this idea was tried in the 1980s and was deemed too slow, difficult and dangerous. The Office of Naval Research has since made significant progress in crane and mooring technologies that would allow for safe and efficient at-sea VLS rearming.

Walton acknowledged the bill that would accompany this plan: CSBA recommends having 143 logistics-related ships by 2048 instead of the Navy’s planned 50, at a cost of $47.8 billion more than the Navy has budgeted for. Walton said that cost, about $1.6 billion a year more than planned, is “considerable” but, if executed correctly, could strengthen the American shipbuilding industry and reduce reliance on foreign shipping.

“The current programmed maritime logistics force is inadequate. What’s traditionally been a U.S. strength now risks becoming a major weakness that undercuts deterrence, invites aggression and could cause the United States to lose a war, especially against China,” he said.

“There are new logistics concepts and capabilities that would allow the fleet to become more operationally resilient by having a fleet that’s larger, more differentiated and by cooperating more closely with the Maritime Administration and the Merchant Marine that could be cost-effective and sustainable over long-term strategic competition.”