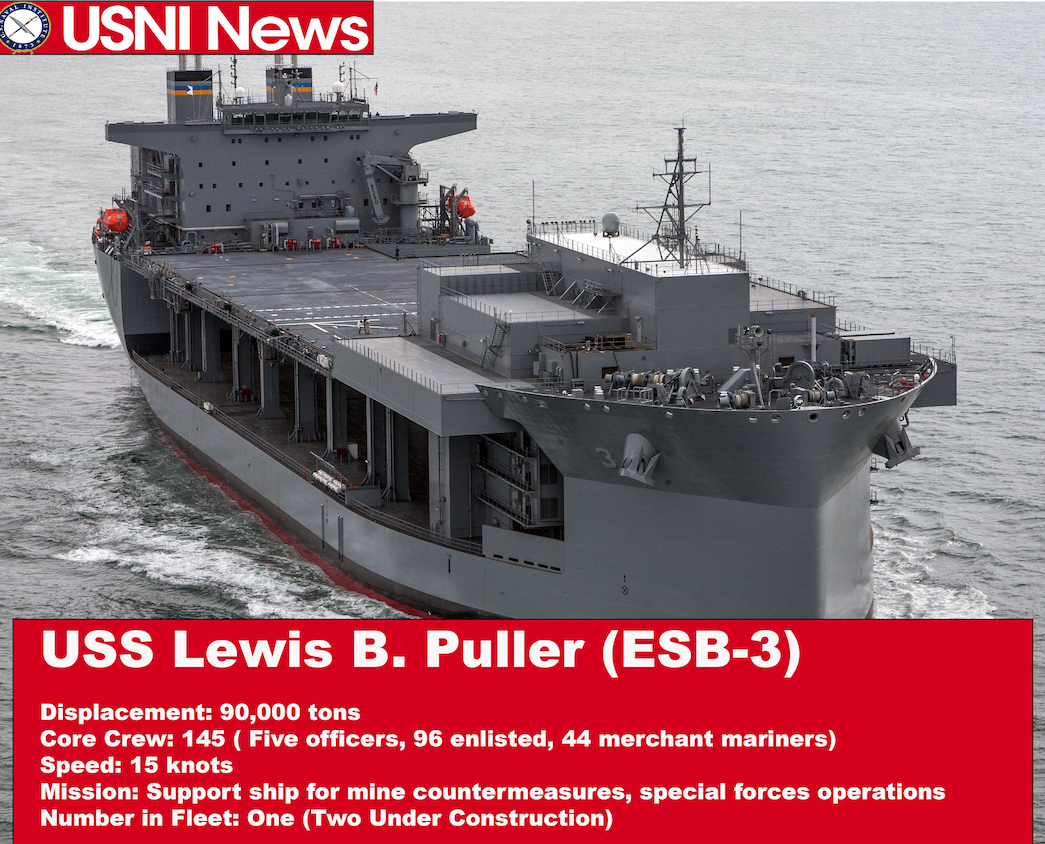

ABOARD EXPEDITIONARY SEA BASE USS LEWIS B. PULLER – U.S. 5th Fleet is experimenting with one of the Navy’s newest warships with a mission to support amphibious, special forces and mine countermeasures operations at sea. USS Lewis B. Puller (ESB-3) is the Navy’s first purpose-built expeditionary sea base in decades, and sailors and Marines are hard at work learning how to innovate with a wide cross-section of U.S. and international military partners.

The ship is already the byproduct of innovation: Naval Sea Systems Command in 2011 took a commercial Alaska-class tanker and scooped out the middle to create the Montford Point-class expeditionary transfer dock (T-ESD-1), and then slapped a flight deck over the top to create the Puller-class ESB. For about $650 million, the Navy gets a ship with a four-spot flight deck for helicopters and tiltrotor aircraft, a massive mission bay with cranes and equipment for small boat and unmanned vehicle operations, and an abundance of unused space waiting to be filled, Capt. Joseph Femino, commanding officer of Puller’s gold crew, told USNI News during a March visit to the ship.

The ship is now based in the Middle East, operating with a blue/gold rotational crewing model – the blue crew has taken command of the ship since the USNI News visit – and the innovation continues as the crews carve out a niche for themselves in 5th Fleet operations.

Much like barges used during the Vietnam War and the Iran-Iraq War, Puller acts as an afloat base for mine countermeasures helicopters and special operations teams in small boats operating in theater, offering rest for those operators, refueling for their boats and helos and a hub for maintenance gear and supplies. The now-decommissioned Ponce (AFSB-I-15), an amphibious transport dock saved from decommissioning in 2012 and given a second life as an interim afloat forward staging base in 5th Fleet, operated in that same capacity for five years before being replaced by Puller. Unlike those barges and amphib, though, Puller was purpose-built for the mission and given lots of additional space to grow into, and other communities in 5th Fleet want to take advantage of the opportunity they see in Puller.

Early Experiments

Puller arrived in 5th Fleet in August and was promptly commissioned as a warship, whereas it had previously been a Military Sealift Command ship with a USNS designation.

Since that time, Femino said the ship has been busy working with Marines, special operations forces (SOF) and even French amphibious forces to learn how Puller could best support other naval platforms.

Almost immediately, Marines put a Fleet Antiterrorism Security Team (FAST) platoon on the ship to start learning their way around the ESB. In October, a SOF team came out to practice fast-rope drills from their helicopters onto the flight deck and to learn how to bring their small boats onto the Puller mission bay with the ship’s crane. The SOF team has come back four or five times since, Femino said, and while all the ins-and-outs of the tactics haven’t been formalized yet, they are familiar enough with the ship to use it as a tool if needed in a crisis.

The U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) force surgeon has visited the ship to look into possible medical applications. Work with the mine countermeasures community is moving a bit more slowly – even though the Ponce and then Puller were initially requested by 5th Fleet specifically to support the MCM mission – but the crew have been aboard to assess the mission planning spaces and other assets Puller could provide.

The ship features a large mission planning space, which can be left open or broken into up to four closed-off spaces, if multiple teams were embarked at once. Embarked units can use computers and communications gear already in that space or bring their own, and can conduct secret-level work when required.

“This ship is a blank canvas. Whoever wants to come assess what they want, develop what they want, we’ll work to try and get that,” Femino said, adding that he and his blue crew counterpart, Capt. Paul Campagna, have been working with embarked units to think outside the box and consider what new gear, furniture, capabilities and more could be brought in to make the space even more conducive to their mission.

As much planning work as the last few months have involved, trying to understand what MCM crews need versus what SEALs need, and so on, Femino said there has also been an element of just trying something and seeing if it works.

“People bring their things and let’s see how they fit. And then if we need to modify then we’ll modify,” he said.

“When we were with the French, they have an L-CAT, which is sort of interesting, it’s a catamaran landing vehicle. … Well, let’s bring it alongside us, tie it up, let’s use our crane to move – I think they moved a water buffalo, 2,000 pounds, and load it onto (the L-CAT). Now they don’t really want our water buffalo, but the reality is at a certain point they may want to put 2,000 pounds of stuff there, so let’s walk through all those things.”

Femino said his crew – which consists of about five officers and about 100 enlisted sailors, as well as 44 civilian mariners (CIVMARs) who navigate the ship and maintain the hull, mechanical and electrical systems – is ideally suited for this type of experimentation due to being such an experienced crew.

“One of the interesting parts of this, in this experimental part, is the CIVMAR benefit. What CIVMARs represent are people that for their lives have worked on the water. They grew up and went to maritime schools and could be 20 or 30 years in. To me, as someone who also has been like that – I’ve been on the water since I was 12 years old – my eyes and their eyes are very similar, and when we can look at something and, even if it’s non-standard, how can we do it safely? How can we do it without anyone getting hurt and validate what we want? Or if we want to do something, then these are the steps we need to take,” he said.

Upcoming Efforts

Femino had three key answers when asked what the next steps were in experimenting with Puller: address the mine countermeasures mission in a more meaningful way; figure out how to work alongside an Amphibious Ready Group and embarked Marine Expeditionary Unit, rather than bringing smaller groups of Marines onboard Puller itself; and repeat training with units enough that the skill could be used in a contingency if needed.

On the amphibious operations side, Femino said the work with the FAST platoon was excellent, giving those Marines a more mobile and potentially better located basing option in lieu of waiting around in Bahrain. However, he made clear, “we are not an amphib. … The question is, how can we enable the amphibs to do things better?”

For that, he said he had some ideas, but the Navy and Marine Corps need time to practice operations at sea and better understand the role Puller would play in amphibious missions at sea.

Since amphibious assault ships have both fixed-wing AV-8B Harriers and rotary wing and tiltrotor aircraft onboard, which have different requirements for being staged, maintained and launched from the ship’s flight deck, “I could be another four spots of deck. A close-by lily pad, they could come and they could stage [some helicopters], get gas, get fueled so that – say the big deck can launch from seven spots; you take my four spots, now you’ve just increased that significant capability, almost 50-percent more capability of immediate launches,” Femino said.

“This is something we haven’t done, it’s still on the conceptual side. But that’s what we’ve got to do, we’ve got to figure out how we can assist the ARG/MEU.”

Campagna said Marine Brig. Gen. Frank Donovan, commander of Task Force 51/5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (TF 51/5), has said previously that the ESBs “don’t generate combat power, they enhance existing combat power.” With that perspective, Puller and its crew are still working to understand how they could be most useful to ARG/MEU leaders trying to conduct a humanitarian assistance mission, an embassy evacuation, a raid or other amphibious mission.

On the MCM mission, “we’ve done a little bit of work with mine warfare, but quite frankly we haven’t really flushed out all of the mine warfare,” Femino said, while making clear that doing so this year would be a priority.

“We are here for MCM support. We are not here for SOF support, we are not here for Marine support. The reason there was an RFF, the reason they created Ponce was I believe for a request for forces (RFF) to support the mine countermeasures process,” he said, though the Marine and SOF experiments have yielded great returns as an additional capability the ship can provide.

Femino said the ship would first work with the airborne mine countermeasures community, which flies the MH-53E helicopters, to see how they can best support the helos and how the ship could be best reconfigured to optimize those operations. Also on the to-do list, though, is working with the Avenger-class MCM ships in 5th Fleet to see if Puller could help refuel them or support them in any other way.

Femino pointed to events in the May and September timeframes that would focus on mine warfare activities, to help solidify that part of Puller’s mission.

The skipper said he’d also like to work with a carrier at some point, but that overall he has to balance working with a lot of different potential customers versus becoming proficient at working with some of them.

“I think that really it’s about reps and sets: both people that have come along and worked with us a lot and get better and better and enhancing [those operations], or some that we’re still trying to find the opportunity to work with,” he said.

Whoever Puller ultimately supports at sea in a crisis, though, “they need to be able to show up ready to execute,” so Femino said the ship needs to be careful going forward about becoming proficient with the key partner communities before finding new ones to experiment with.

Margin in the Design

Though in the near-term the ship will find its niche in 5th Fleet through experimenting with different kinds of operations, there is an opportunity in the longer-term to actually evolve the ship or others in the ESB class to more precisely meet fleet needs.

Femino, while showing USNI News around the ship, pointed out numerous places on the ship where big, empty voids are waiting to be filled.

“Underneath us is just all these empty ballast tanks,” he said while standing in the mission bay.

“There’s a potential in the future that says, we could convert them to things, because they’re just space. So there’s one way where for 40 years they stay just space; there’s a certain way where 10 years from now we decide this is what we’d like to build into that space.”

While standing on a platform in the mission bay, he noted that the platform could be extended to create “free” space that wouldn’t take away from boat operations or storage beneath.

“If we wanted to, or some entity wanted to, build platforms like this, I could store boats here; I could build a hospital here; I could do anything I wanted, and it wouldn’t be at the cost of anything I’m designed to do, it would just be at the cost of what it takes to engineer it, design it, build it,” he said.

With the ESBs being permanently attached to a numbered fleet – Puller will remain in 5th Fleet, the future USNS Hershel “Woody” Williams (T-ESB-4) will deploy to 6th Fleet and the third ESB will likely go to 7th Fleet in the Pacific, Femino said – each hull could make different alterations based on what operations and capabilities are most in-demand in that region of the world.

“Our hospital ships are going away, so I actually had the force surgeon on today, I said, listen, I could build you all the beds you want across this (raised platform in the mission bay). If someone shows up with money and instead of spending the money we spend on Mercy and Comfort for a year of operations, they just build me out with that,” he said.

“The one in CENTCOM may never need a gigantic hospital” due to being a reasonable flying distance to the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, where wounded servicemen in the Middle East are typically taken. But an ESB operating in the Pacific or near Africa or even in U.S. 4th Fleet in South America – where the fourth ESB that the Navy will build with Fiscal Year 2018 funds could potentially end up – could make use of a hospital capability due not being near a major medical hub and to support the major partnership-building activities in those regions that revolve around medical treatment.

As a less permanent investment, Femino noted that the mission bay and part of the flight deck are covered in padeyes for CONEX boxes to connect to. The ship already operates the Scan Eagle unmanned aerial system out of a box and has experimented with an Expeditionary Resuscitative Surgical System (ERSS) team to establish a portable Role II medical capability out of a box, complete with its own triage and operating rooms and storage for the blood, medical supplies and other support items. One group of SOF personnel even brought their own gym in a CONEX box.

Femino said the mission bay could host rows and rows of CONEX boxes to support a major non-combatant evacuation operation (NEO) or humanitarian assistance mission; could take a couple boxes with armories, decompression chambers for divers, office space or berthing for small units; could fashion a makeshift prison, as Ponce did at one point; or whatever else was asked of the ship by embarked forces. Femino said the ship has all the electrical and utility connections needed for whatever an embarked force can dream up.

The medical capability will be added to the ESB starting in 2019, Femino said, but any future additions or alterations to the ship are still up for debate, pending future fleet needs and the success of all the experimentation the ship is still conducting.