This post has been updated to correct the hull number of USS Thresher.

Recently released documents about the sinking of attack submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593) show the lengths the Navy took to assure the public that the incident wold not result in an environmental catastrophe.

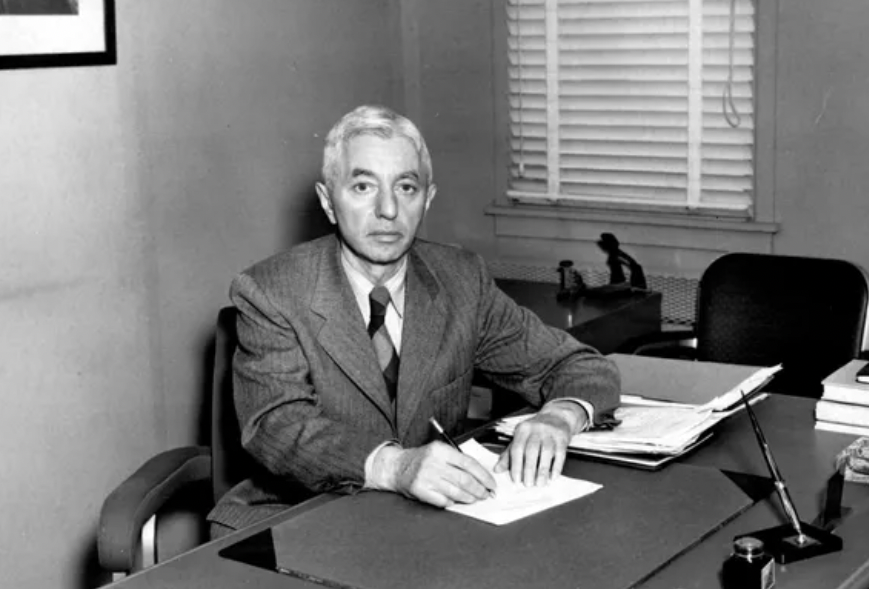

The first director of Naval Reactors, Vice Adm. Hyman Rickover, worked to reassure the public and Congress that there was no danger of a nuclear explosion or a major radiation leak contaminating the seawater more than 200 miles off Cape Cod following the 1963 sinking of the attack submarine.

“There is no way the nuclear material in THRESHER could be made to undergo a nuclear explosion, i.e. there is no danger that it can or will explode like a bomb.” On radiation, the draft said that “outside the ship [it] is normally undetectable,” according to a draft statement from Rickover.

“Rickover was very attentive to public opinion,” retired Navy Capt. James Bryant told USNI News via email. He added that Rickover was focused on any public perception of nuclear weapons or energy, which included judging the impact of Japanese horror/disaster films of the 1950s and 1960s movie monsters being created from nuclear radiation like the giant moth, “Mothra” or the flying space turtle, “Gamera.”

Rickover “was very conscious of public affairs; he [also] was very conscious of keeping things out [of public discussion] when it suited him,” Bryant said. This also meant Rickover was “committed to protecting his [nuclear] program through unwavering operational and design safety.”

He said this was in keeping with the Eisenhower administration’s 1958 decision to allow USS Nautilus (SSN-571) to make a port call in New York City following its transpolar crossing. The visit highlighted Navy expertise and nuclear safety. Rickover greeted the crew on its arrival.

Bryant successfully brought the suit compelling the sea service to release the documents it held on subsequent investigations into what caused the submarine implosion during deep diving tests on April 10, 1963. All 129 aboard the submarine died.

Although reactor safety was stressed, Bryant and his volunteer research team said in a Proceedings article that other shipboard systems, like handling seawater, “were far less firm in their design, construction, and testing.” There also was not a recovery system in place for submarines operating at these depths.

A year after the sinking, the Navy launched the Submarine Safety Program, known as SUBSAFE, as a quality assurance initiative.

The latest documents, with a cover notice that they are intended for Navy Secretary Fred Korth, were written within a few days of Thresher’s implosion and about two weeks before Rickover was scheduled to testify before the court of inquiry that had convened in Portsmouth, N.H.

In his 12 minutes of public testimony to the court, Rickover, sticking closely to the draft, said it was “physically impossible” for the reactor to have exploded on the first-of-its class fast attack submarine.

He added that the naval reactors’ design did prevent an environmental disaster.

Bryant said that in building Thresher–class submarines, the emphasis was on speed and the ability to dive to previously unrecorded depths for operations in the far northern Barents Sea to counter Soviet advances in missiles and nuclear weapons.

In his written response to USNI News, Bryant said the sub’s construction under the pressure of the Cold War period meant “there was not an appropriate level of appreciation for increased operational risk” at those depths.

Back then, there was some of the animosity between Rickover and the diesel boat veterans of World War II, Bryant told USNI News. That in part stemmed from his choice of officers to serve in the nuclear Navy. “He did not want guys who would break all the rules,” so he drew upon surface warfare officers and aviators to fill out the ranks because “they followed procedure.”

Bryant estimated there are 16,000 “pinks,” as the carbon copies were known, still yet to be released. He added that Rickover “read all of them.”

In the material already declassified, Bryant said there is heavy redaction. Sometimes it occurs in taking out the name of message senders in unclassified documents or the performance of materials that have no relation to nuclear operations.

Bryant and his team are continuing to work on determining the causes of Thresher’s loss, he said. Areas of interest now include why were different Sound Surveillance System Low-Frequency Analyzer/ Recorder displays briefed to the court and posted in the secretary’s reading room; what was the actual performance of a critical valve as the crew readied the submarine to return to service after a yard availability; and lastly, inconsistencies in a main ballast tank blow test after the sinking versus what is known about Thresher when it was in distress.