SAN DIEGO, Calif. – The Marine Corps’ reshaping and retooling of its force with smaller units dispersed across islands and the littorals require reliable command and control systems and secured networks that work with both Marine Corps and Navy platforms, officials say.

The success of maritime operations in contested environments against a peer enemy – like China’s growing military – will depend on having integrated command and control, computers, and intelligence systems in both Navy ships and in Marines’ hands.

“We’re going back to our amphibious roots again, trying to make sure that we’re helping support the Navy with sea denial and sea control capabilities,” Marine Capt. Steven Gore told USNI News. “A lot of our focus of efforts is working C4I systems and seeing how the digital fire threats [and] how the Marine Corps is going to support sea denial fire capabilities, and making sure that that gets routed properly through the C4I systems the Marine Corps and the Navy jointly use aboard L-class ships.”

Critical to that, Gore said, is “getting that process down … to shorten the time frame for those kill threats, with kill webs and kill chains.”

So Marine Corps Tactical Systems Activity officials are looking to industry, academia and federated labs to leverage new ideas, concepts and technologies that will ensure naval integration for that future fight with Marines’ Force Design 2030 in mind.

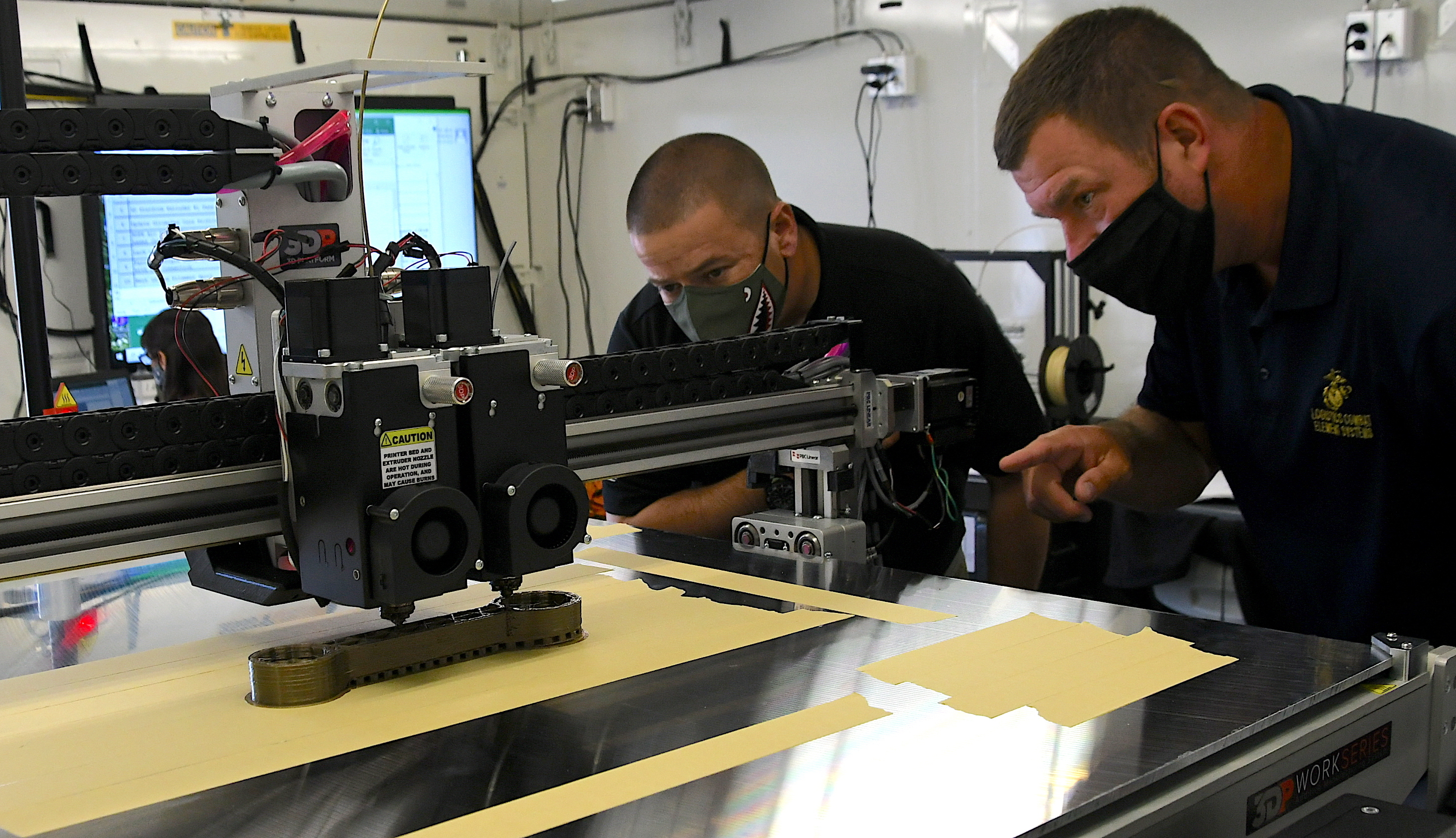

Last year, MCTSSA got the green light to work directly with the tech industry when it was designated as a technical activity. MCTSSA falls under Marine Corps Systems Command and does test and evaluation, engineering and deployed technical support for the Marine Corps and its C4I systems.

That June 2021 decision by the Chief of Naval Research meant “we now have the ability to operate outside of the federal acquisitions regulations, FAR, to a certain degree, and start cooperating with industry directly,” Gore told an audience during WEST 2022, an annual defense conference hosted by the U.S. Naval Institute and AFCEA. “There are some limitations with that. We can’t sign any contracts or anything like that. But there are some cooperative engagement efforts that we can do.”

“The idea is we can start doing a little bit more type of work for technologies that are already out there, technologies that are maturing,” he said, “and work with industry and academia to get those types of technologies into the Marine Corps much faster than the actual defense acquisition system would allow it to.”

Seamless naval integration will be even more critical to the Marines’ Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept in the Indo-Pacific region.

“As we’re assessing the enemy’s capabilities for disruption and detection, now we have to see how our C4 systems will operate in a degraded environment,” Gore said. “What kind of [electromagnetic] signature do our systems put out? What happens when it starts getting disrupted? How will that affect our C2 systems? We’re doing those assessments, but there’s a lot of room for improvement.”

Among the first technology partnerships is with University of California San Diego’s Artificial Intelligence Group. MCTSSA’s Advanced Concepts Cell is working closely with the university to realize any AI technology “that can be immediately leveraged to help with C2 systems, some of the technologies that we use for handhelds,” he said, noting “anything that can leverage a training tool or maintenance, that we can work with Training Command, we’d be very interested in utilizing that.”

Last year, MCTSSA also joined the Federated Lab Consortium, enabling it to partner with all Defense Department labs, as well as commercial labs, to potentially get technologies incorporated into the Marine Corps much faster.

While MCTSSA doesn’t fully do research and development, Gore said, tech transfer enables the lab to work cooperatively and do more R&D with industry partners. “They can come in and utilize our labs … to help mature those technologies that we cooperatively work on those and it should theoretically help both partners involved,” he said.

Naval Integration Challenges

The Marine Corps’ refocus on maritime and amphibious operations, after two decades largely tied up in land-based operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, has spotlighted gaps in naval integration. Little happened to tackle those gaps over the two decades of land-based warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq, noted Gore, so challenges remain to ensure seamless integration. MCTSSA officials are eager to find existing technologies, products and ideas from industry partnerships and academia that can go after solutions.

A lack of integration training is a key obstacle to ensuring that C4I systems work as expected, and seamlessly when Marine Corps units are aboard Navy ships to train and operate overseas. “We see a lot of a lack of trained personnel,” Gore said.

It’s important for Marines to work on Navy gear, including shipboard communications, and sailors to work on Marine Corps gear so they get familiar with operating and maintaining the other service’s gear and equipment well before they have to use it for real while at sea or operating ashore, he said. That includes working through the tactics, training and procedures “on how they are going to conduct missions … and make sure all of that works.”

But not many Marines, including those with Marine Expeditionary Units, get familiar with those systems they’ll use or sort out connectivity issues until they’re underway on a large amphibious ship for unit-level training.

Units can visit MCTSSA’s lab facilities at its small, oceanside campus at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton to practice on the same gear they’ll use on a ship, Gore noted. Facilities include the realistic “LFOC ashore” trainer that replicates the Marines’ landing force operations center aboard amphibious ships, down to consoles and switches, but it’s the only one like it in the service. “More and more people want to see how their units are going to do amphibious operations, so they want to utilize the LFOC” lab, he added.

Seeking Integration Solutions

Gore noted other challenges to naval integration that officials say industry might be able to help them resolve, including:

- A “lack of a persistent C4 environment.” Maintenance requirements of Navy amphibious ships, with hulls tied up at the pier or at a shipyard for overhaul and modernization after an overseas deployment, means a year or two or longer that Marines can’t access the ship and its onboard systems. “By the time that ship gets back, the C4I infrastructure, the networks, everything has been torn down,” he said, “and it’s basically like starting from scratch over again.”

- A maintenance availability often provides the latest equipment, such as new versions of CANES, the Consolidated Afloat Network and Enterprise Services, that “is allowing some persistence there. But any tools that can help expedite the rebuilds of that automation of network builds are some technologies that we’re looking to leverage,” he said. “If there’s something that we can do to sort of map out the networks before … the MEUs get on ship, [like] a tool that that sort of scans the complexity of the CANES shipboard network, that would be a great assistance for our team.”

- Lag in installing new shipboard systems. The Navy modernization process “takes a very long time to field installs, new programs of records,” he said. “As soon as a ship comes out of the docks, it’s not ready to have a lot of the C4 systems installed aboard, and it won’t get those completely fielded for another four or five years out.”

- “We’re running into a lot of issues of immediate availability of ships coming out of the yard,” he said. As C4I systems get upgraded, the technologies they want “are outpacing the Navy’s modernization process. Thus, we’re looking for ways around it,” he said. That includes helping MEUs and ship’s force with “workarounds” so they can do non-pertinent installations.

- Certifying new systems. “As new systems come onboard, they have to get fully accredited” by the Navy certification program, a process MCTSSA teams support, but that’s also time- and labor-intensive. “So anything we can do to automate and speed that up would be greatly beneficial,” Gore said.

- Ensuring interoperability. The Marine Corps is lacking in its afloat interoperability requirements, particularly with previous programs-of-records that “don’t have a requirement to test in an afloat environment,” he said. So it falls to MCTSSA “to do that afloat integration. There’s no actual guidance from SYSCOM or from the program offices, the Marine Corps program offices, to say that we need to do this testing. That’s all on our own schedule, and on our own dime.”

- Gaps in common operating picture. While the Navy and Marine Corps use the same COP, software and hardware, “they have very different needs,” he said. The Navy’s COP “filters out land tracks. The don’t need to worry about the land most of the time. They only worry about where the ships are, where the aircraft are,” he said. “So when the MEUs come aboard and try to fall in on the Navy COP systems, they don’t see where their own forces are. The Marine Corps now has to set up their own COP picture, their own COP feed, and that just eats up bandwidth, system resources.”

“We’ve gotten no traction as far as changing the policies for big Navy,” Gore said, “so we’re looking to see if there’s any tools out there that can integrate or possibly pipe around a feed as far as land tracks and the COP feed that the Marine Corps needs.”