The Navy wants to emphasize the development of enablers for unmanned systems – the common interfaces and control stations, the networks, the secure data formats, the autonomy behaviors – as it pursues a hybrid manned/unmanned fleet for the future.

The Navy wants to emphasize the development of enablers for unmanned systems – the common interfaces and control stations, the networks, the secure data formats, the autonomy behaviors – as it pursues a hybrid manned/unmanned fleet for the future.

However, the platforms still matter – and most of the ones the Navy wants to leverage in the coming years are still in development.

Several platforms were discussed during a recent House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee hearing, providing a glimpse into the programs’ statuses after a year of missed in-person conferences and other opportunities for public program updates.

MQ-4 Triton

Of all the programs discussed during the hearing, the furthest along in fielding is the MQ-4 Triton. Two vehicles are currently operating out of Guam, providing maritime awareness to operators in the area. The program had previously been on track to reach initial operational capability this year, which was itself a delay after the deployment of the first two vehicles was postponed from 2018 to 2020. Now, the program is facing additional delays as the service tries to ensure the vehicles carry the right payload to help operators in the Pacific.

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), said during the March 18 hearing that the Navy was learning a lot about how to use the air vehicle to support warfighters in a relevant way.

“It allows us to create a more complete picture of what is out there versus what we think is out there” in the vast ocean and air space, he said.

“So to me it’s a validation – and having been an operator in the Pacific, sometimes it corrects a mis-ID, for lack of a better word. So I think Triton will add tremendous value there.”

Despite that value, the Navy did not request funding to buy any more vehicles in the Fiscal Year 2021 budget request. HASC led an effort to insert funding for one, to keep the production line running.

Jay Stefany, the acting assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition, said at the hearing that two vehicles are in early fielding now and that 19 more are on contract with manufacturer Northrop Grumman, including the one that Congress put into the FY 2021 budget.

“It was a relatively small risk for us to take a year off” from production with so many already under contract for Northrop Grumman and its subcontractors to work on, he said, and the Navy plans to pick back up Triton acquisition in FY 2022 or 2023, depending on the budget. Stefany said any breaks in buying the systems aren’t expected to create any quality or cost issues for the production line.

Among the reasons for taking a break is that the Navy wants to figure out what capability it has for forward operators and what improvements it wants to add. Kilby and Stefany were vague on the details but said that they were already looking at adding capability to the system.

“That fleet or [combatant command] feedback is a critical thing that we’re considering as one of our factors – so we received feedback on an improved mission set, and so we decided to take a little pause to make sure that we get the technology for the new mission set in place before we start building more,” Stefany said.

“And it’s not that we’re going to stop; it was feedback from the fleet that we needed that extra set of mission capability.”

“Future variants will have increased capabilities that will add even more to that mosaic of sensors to provide feedback back to the warfighter,” Kilby said.

“So we’re already seeing great returns, we’re learning how to operate it, we’re understanding the limitations now and addressing those to make sure the future variants of that provide the most robust capability we can.”

MQ-25A Stingray

Perhaps drawing the most questions and concerns from lawmakers was the MQ-24A Stingray, the first carrier-based unmanned aircraft the Navy will field. It will primarily serve as a tanker for the carrier air wing and may also conduct some intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) – but lawmakers said they were more interested in the Navy achieving some kind of unmanned strike platform in case the sea service found itself in a fight against a high-end adversary.

Kilby explained that the whole point of the Stingray program was to start with a basic airframe and a basic mission set and learn how to get comfortable with maneuvering an unmanned plane around an aircraft carrier – launching and recovering from the flight deck, moving it up and down the aircraft elevators, maneuvering through the hangar for maintenance and more. The tanking mission is relatively straightforward – the Stingray would either conduct aerial refuelings near the carrier with aircraft that were running low on fuel and struggling to land on the deck, or conduct aerial refueling farther from the carrier to keep jets on station during their missions. The simplicity, Kilby said, is what would allow the Navy to work out the basic building blocks first before moving to a more complex mission set.

“There is some payload capacity in that vehicle that we think has great promise for us. So I think initially we would transition to ISR, but in an air wing of the future view … we think we could get upwards of 40 percent of the aircraft in an air wing that are unmanned, and then transition beyond that. So I think the logical step would be trying to follow a logical crawl, walk, run – let’s figure out how to handle it in the air wing, let’s move to ISR, maybe electronic attack, strike and then other things as complexity grows across that mission set,” Kilby said.

In the near term, this has the benefit of automatically adding more endurance to the tanking mission – an unmanned tanker can stay in the air much longer than a manned F/A-18E-F Super Hornet that’s serving as a tanker for its fellow jets. In the longer term, it buys the Navy some time to refine its thinking for follow-on concepts of operations or even follow-on UAV designs.

On CONOPS, Kilby said the Stingray would first be operated via a control station on the aircraft carrier. Down the road, though, he hoped to achieve some kind of connection between the unmanned tanker and the manned aircraft, so that the air wing could coordinate their own aerial refuelings closer to their operating area or away from the carrier if the ship was near bad weather. This could take some time, as the Navy would need to improve its network capabilities and implement some kind of low-probability-of-intercept communication between the Stingray and the manned aircraft.

Taking a more incremental approach by starting with the tanking mission would also let the Navy figure out how much capacity the MQ-25A airframe has for additional payloads versus whether the service might need to develop a new airframe for certain heavier or power-consuming payloads. Stealth could also become an issue, with the Navy perhaps needing a more simple and lower-cost airframe for some missions and a stealthier airframe for other missions.

“My view is, we need to introduce those capabilities with successive increasing levels of complexity to complement the air wing that we have today,” Kilby said.

“I don’t want to sign up for that before we’ve met some of these rudimentary things to integrate capability in the air wing, and I think the MQ-25 is our way to start that integration.”

Boeing conducted the first flight of the MQ-25 air vehicle with the refueling equipment onboard in December, after a September 2019 first flight without the gear installed. The Navy had previously said it wanted to field the first vehicle to an air wing in 2024, but Kilby said during the hearing the Navy was looking at a 2024 to 2026 timeframe for delivering the initial MQ-25A capability.

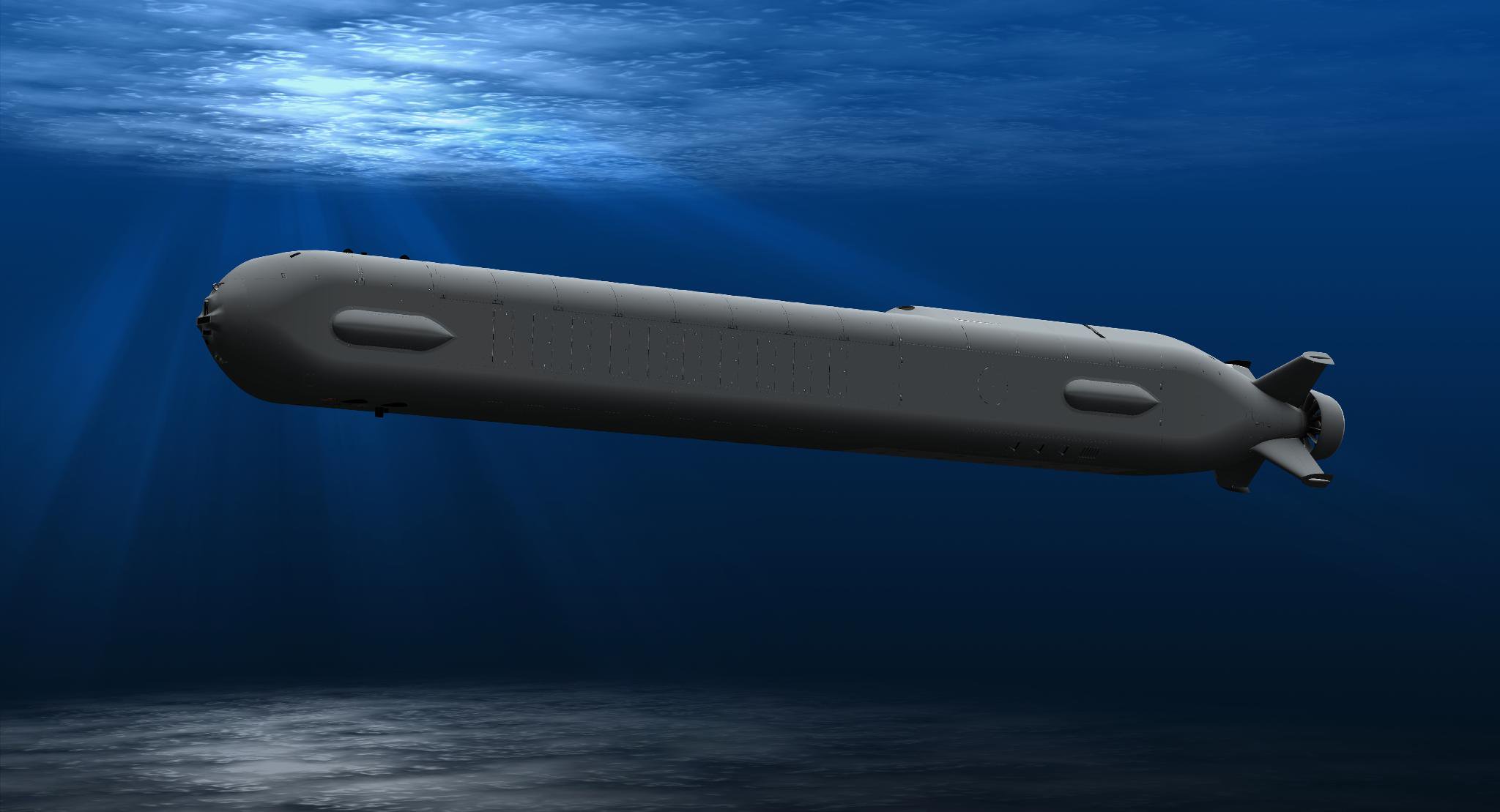

Orca XLUUV

On the unmanned underwater vehicle side, the Navy’s largest vehicle in development is hitting some snags, though Kilby said it was a production issue more than a fundamental issue with the service’s requirements.

Kilby said the Navy wanted the Orca Extra Large UUV to lay mines in the water, among other clandestine operations. But building a UUV that can do that is more complex than it sounds, he told lawmakers.

“I’ve got to avoid fishing nets and sea mounts and currents and all the things. I’ve got to be able to communicate with it, sustain it. I’ve got to maybe be able to tell it to abort a mission, which means it has to come up to the surface and communicate, or get communications from its current depth. Those are all complexities we’ve got to work through with the [concept of operations] of this vehicle,” he said.

“In its development, though, there have been delays with the contractor that we’re working through, and we want to aggressively work with them to pursue, to get this vehicle down to Port Hueneme so we can start testing it and understand its capabilities. And to me the challenges will be all those things – the C2, the endurance, the delivery of the payload, the ability to change mission potentially – those are all things we have to deliver to meet the needs of the combatant commander.”

Boeing is on contract to build five XLUUVs, which were supposed to be delivered by 2022. Construction on the first vessel didn’t begin until late last year, though, and Kilby categorized the program as alive but delayed.

Asked by seapower subcommittee chairman Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) if Orca was proving to be a program that had failed and the Navy needed to cut its losses on, Kilby said, “I think we’re going to get these first five vessels, and in the spirit of the committee, we want to make sure we’ve got it right before we go build something else. I think it’s scoped out ideally, we’ve got to get through those technical and operational challenges to go deliver on the capability we’re trying to close on.”

He said earlier in the hearing that “we are pursuing that vehicle because we have an operational need from a combatant commander to go solve this specific problem. That vessel really hasn’t operated – the XLUUV is, as you know, a migration from the Echo Voyager from Boeing with a mission module placed in the middle of it to initially carry mines. We need to get that initial prototype built and start employing it start seeing if we can achieve the requirements to go do that mission set. And I think, to the point so far made several times, if we can’t meet our milestones, we need to critically look at that and decide if we have to pursue another model or another methodology to get after that combatant need. But in the case of the XLUUV, we haven’t even had enough run time with that vessel to make that determination yet. Certainly, there’s challenges with that vehicle, though.”