The sea services see themselves moving toward a future where they are just as likely to perform a mission with an unmanned platform as a manned one, based on the specifics of the mission and what assets are available. A third of the Navy’s fleet and half of Marine Corps aviation could be unmanned under this hybrid vision the two services are pursuing, which they argue in a new Department of the Navy Unmanned Campaign Framework is necessary to stay ahead of adversary capabilities without breaking the bank.

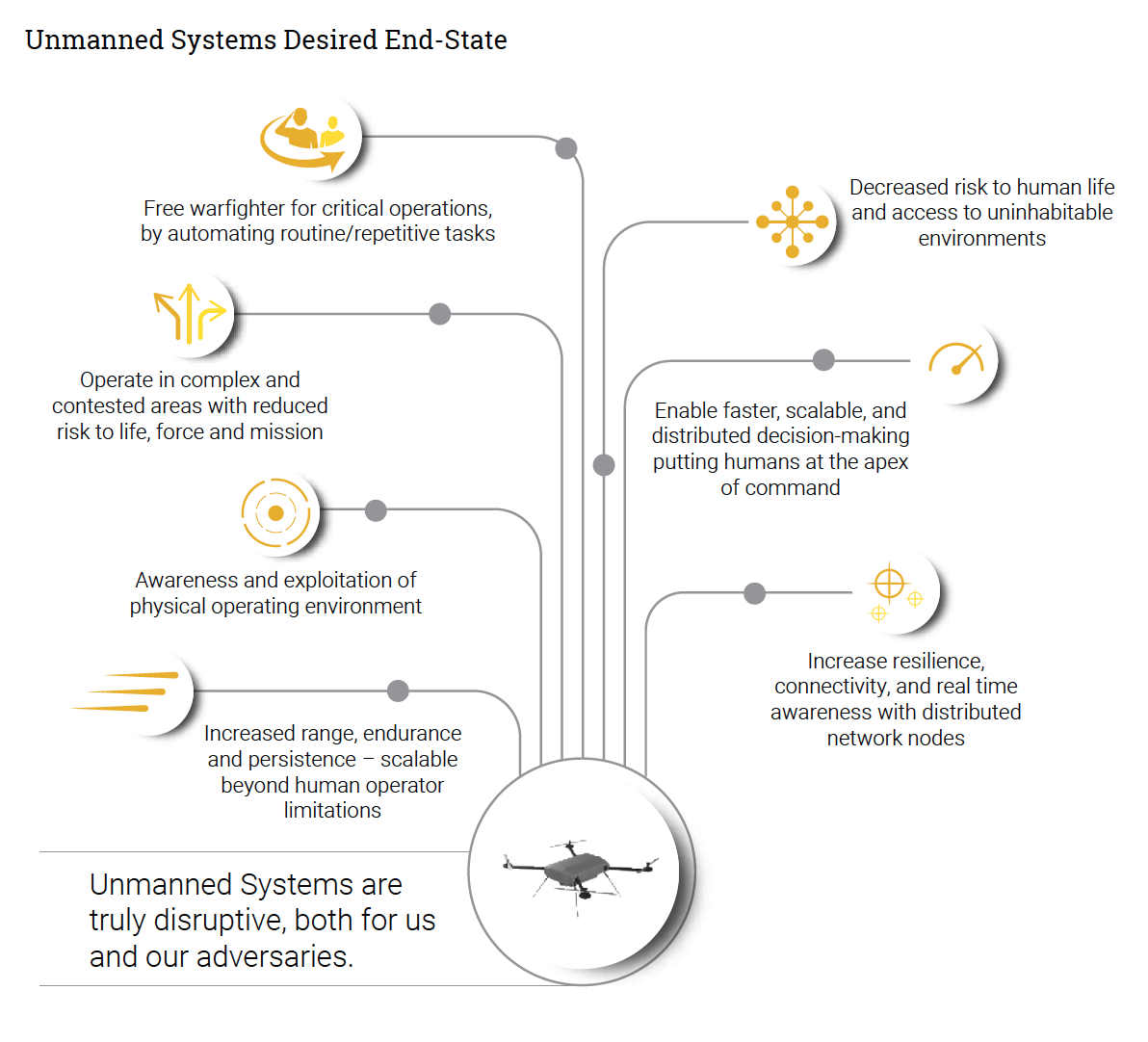

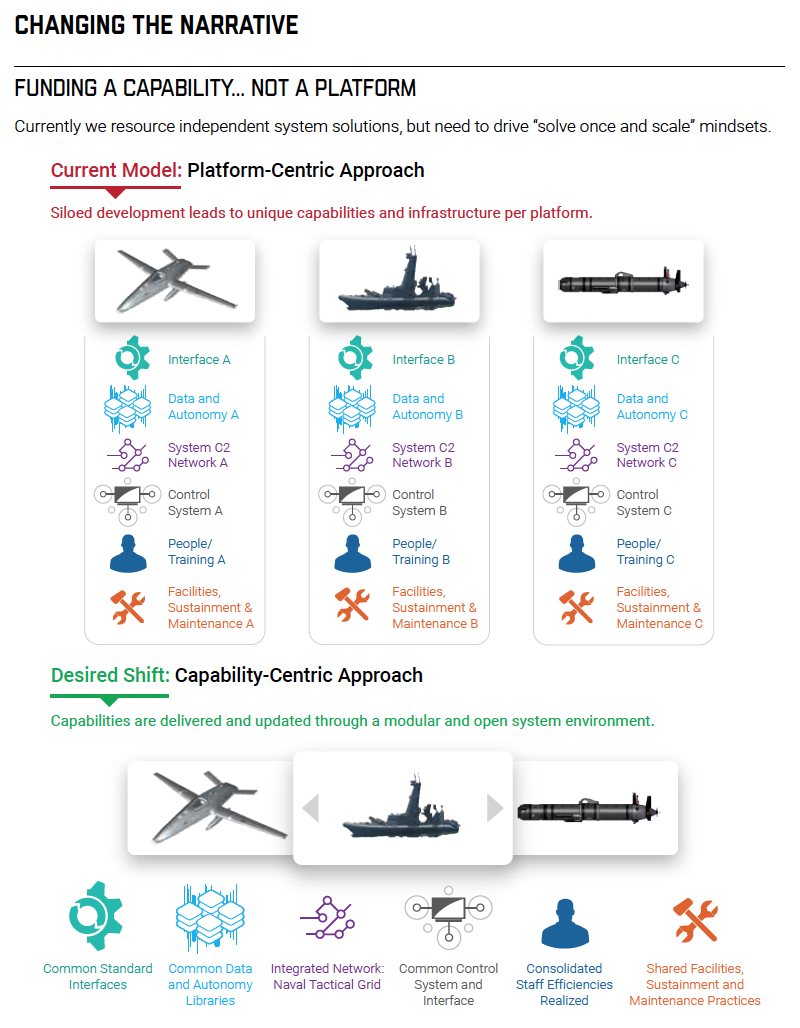

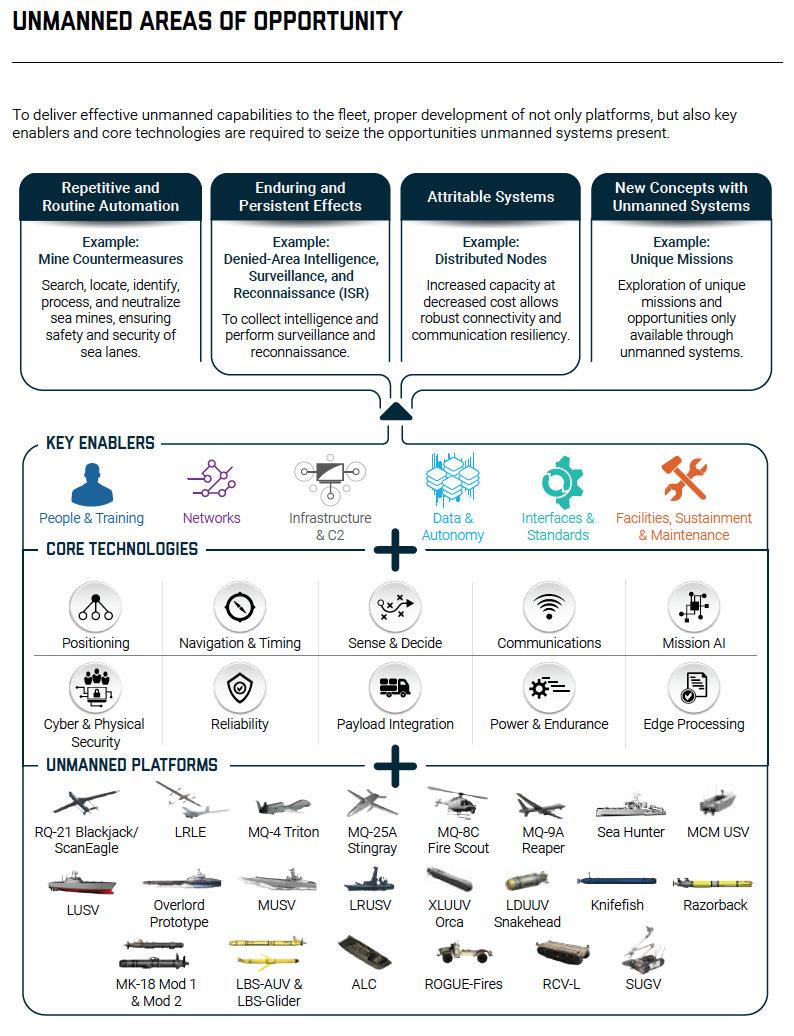

However, achieving this vision will require the services to buck the budgeting system in a way they haven’t had to before: they can’t just develop and buy new unmanned aircraft, surface vessels and underwater vehicles, but they’ll also need to invest in enablers like artificial intelligence and machine learning, networks, data standards, command and control systems and more – which will require constant focus from top leadership to ensure that these less tangible spending items don’t fall through the cracks in a platform-centric budget process.

The Unmanned Campaign Framework states that, “Autonomous systems provide additional warfighting capability and capacity to augment our traditional combatant force, allowing the option to take on greater operational risk while maintaining a tactical and strategic advantage. The Navy and Marine Corps are already operating unmanned systems, and going forward will seek to achieve a seamlessly integrated manned-unmanned force across all domains. The question is not ‘if’ the Naval force will prioritize and leverage unmanned platforms and systems, but how quickly and efficiently, in resource-constrained environments.”

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the Navy’s deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), told reporters today that the vision for a hybrid fleet may be a big change for some, but the need for it has been well proven out by wargaming.

“The global security environment as characterized by great power competition necessitates this shift from traditional force structures to a hybrid force of manned and unmanned platforms working together to create a greater naval force for the joint force. So unmanned systems in themselves aren’t a goal, they’re an enabler for a capability based on a threat that is rapidly accelerating,” he said.

He also stressed that adding unmanned systems to the fleet in greater volume and to conduct a broader range of missions doesn’t fundamentally change how the Navy and Marine Corps will fight and it doesn’t put anyone’s jobs at risk: the services will still have to conduct surface warfare, or they’ll have to clear the way for Marines to land on a beach or they’ll hunt for submarines. Just as the services have already moved to tackle those mission areas from a multi-domain approach – having surface strike options from U.S. surface ships, submarines and aircraft – they’ll now have both manned and unmanned options too, based on the specifics of the mission.

Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. David Berger wrote in his introduction to the document, “The campaign plan serves as a starting point for the Marine Corps to understand that unmanned systems must and will take on greater importance in our near future. Concepts such as half of our aviation fleet being unmanned in the near- to mid-term, or most of our expeditionary logistics being unmanned in the near- to mid-term should not frighten anyone. Rather, these ideas should ignite the creative and cunning nature of our Marines so that our forward-deployed forces are even more lethal and useful to the joint force.”

During the media call, Lt. Gen. Eric Smith, deputy commandant for combat development and integration, addressed the issue of hesitancy to embrace this new hybrid fleet concept.

“There are folks who may not wish to change the way they currently do business because they’re comfortable with it. What he’s saying is, for everyone – for young Marines, for commanders, for the retired community: don’t be frightened by the fact that you may have a larger percentage of your aviation community be unmanned, that you may have unmanned systems on the ground. And frankly even to the public, who we serve: these systems that we are procuring are remotely operated, on their way to autonomous,” but will still have Marines in the loop and making all decisions about using lethal effects.

For example, Smith said, an artificial intelligence tool that can monitor real-time video footage from a large unmanned aerial system in the sky would be of great use to the Marine Corps without putting anyone out of a job: instead of a young intelligence analyst having to monitor that footage in real time, the lance corporal can wait until the AI tool finds the enemy ground formation or ship at sea and then use his or her training to help understand what the adversary might do next and what actions the Marines should take.

“These systems enable commanders” is the message he tried to drive home.

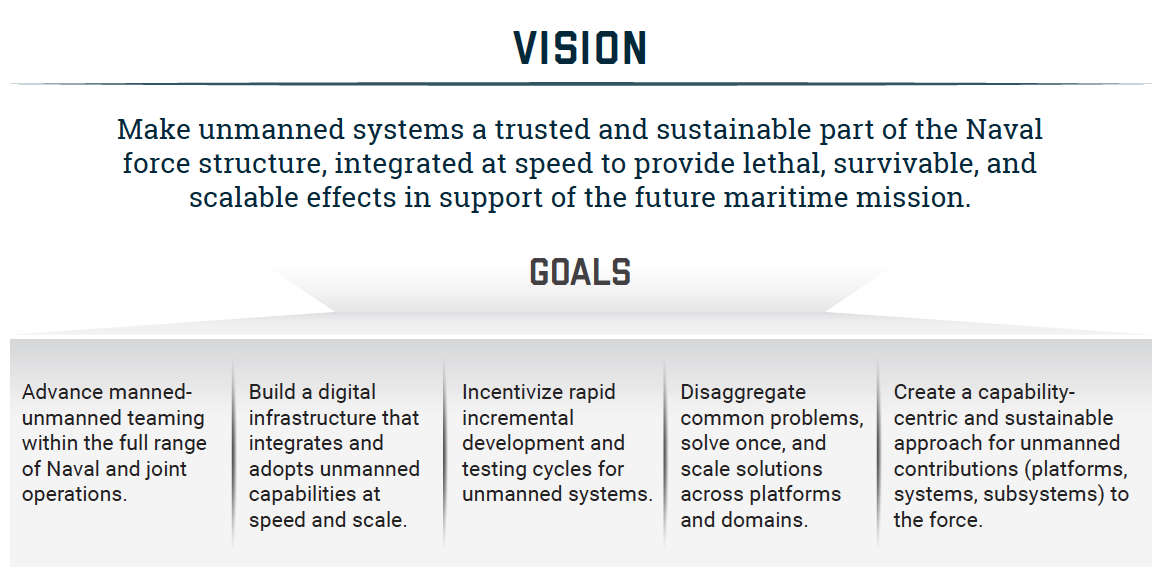

The Unmanned Campaign Framework lays out a vision of “Mak[ing] unmanned systems a trusted and sustainable part of the Naval force structure, integrated at speed to provide lethal, survivable, and scalable effects in support of the future maritime mission.”

“It is imperative that we employ new and different strategies to win the future fight. Unmanned concepts allow us to rewrite the narrative on traditional warfare. Through a capabilities-based approach we can build a future where unmanned systems are at the front lines of our competitive advantage. The Naval force needs to move toward a capability-centric proactive environment able to incorporate unmanned systems at the speed of technology, to provide maximum agility to the future force,” it continues.

In some ways, the Navy and Marine Corps are already moving in this direction. Smith noted that many of the early unmanned systems in all domains (UxVs) that were fielded were urgent operational needs from the warfighter, meaning the unmanned systems were built with speed-to-fleet in mind instead of how they might fit into a larger network of manned and unmanned vehicles and weapons. But now, as some of those oldest systems are aging out and being replaced by new systems, there are already opportunities to take a smarter approach and focus on commonality across interfaces, networks, data formats and more.

For example, the Navy separately fielded a medium-sized unmanned underwater vehicle for the explosive ordnance disposal community and another for the submarine community. The two are now being combined into a common MUUV program that will meet both communities’ operational needs while simplifying the inventory and picking a solution that can leverage work being done on developing a common controller system and autonomy software, and can tap into the Navy’s overall common operating picture.

An unmanned aerial vehicle delivers a payload to the Ohio-class ballistic-missile submarine USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN 730) around the Hawaiian Islands. Underway replenishment sustains the fleet anywhere/anytime. This event was designed to test and evaluate the tactics, techniques, and procedures of U.S. Strategic Command’s expeditionary logistics and enhance the overall readiness of our strategic forces. US Navy photo.On the Marine Corps side, the service has been testing and operating the RQ-21A Blackjack small UAV for the better part of a decade, but the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit is experimenting with other options such as the Martin UAV V-BAT, which could also be used from a ship or ashore and provide the MEU commander an aerial surveillance capability.

“The Marines just want that capability; and when that capability arrives, is tested, experimented, wargamed and is validated and then we can do it to scale, then there’s no need for a previous thing that was doing that but not doing it as well,” Smith said, adding that whatever solution the Marines pursue could provide commanders with improved capability while also fitting into the vision of common networks and interfaces for the hybrid fleet.

The services aren’t just upgrading their legacy UxVs to fit this new construct, they’ll also be experimenting with and eventually investing in many more unmanned systems to conduct missions never before associated with unmanned craft. The Marine Corps has been particularly outspoken about its excitement to use unmanned craft on or under the water’s surface to deliver supplies to Marines scattered across island chains, for example, or to use unmanned Joint Light Tactical Vehicles to haul around anti-ship missiles.

A key challenge to the services will be the nature of the budget process itself. In the Navy, for example, a program manager oversees the development, acquisition and fielding of the system, but a resource sponsor in a separate office on the chief of naval operations’ staff – which resource sponsor it is depends on whether it is used on, under or above the sea – determines how much money it needs to stay on track. That dollar amount gets thrown into a Navy budget proposal overseen by yet another office on the CNO’s staff, which then goes to the Secretary of Defense and eventually on to Congress, where it could be overhauled. In the future hybrid Navy, not only will each platform fall under separate program managers and resource sponsors, but so too will the autonomy packages, payloads and networks they all rely on, meaning that multiple program managers and resource sponsors will have to stay in sync. Otherwise, the Navy could have an unmanned ship without the right command and control tool to operate it, or a payload without a reliable unmanned airframe to carry it.

The Department of the Navy in June 2015 created a Director of Unmanned Systems (OPNAV N99) position on the CNO’s staff and in October 2015 created an office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Unmanned Systems, both of which were meant to tackle the issue of common enablers for unmanned systems across domains. However, N99 was eliminated in February 2017 and DASN Unmanned in May 2018.

Since then, commonality efforts have taken place at the programmatic level, such as within the Program Executive Office for Unmanned and Small Combatants. Last fall the Navy tapped Rear Adm. Doug Small, commander of the Naval Information Warfare Systems Command, to lead a Project Overmatch that would “develop the networks, infrastructure, data architecture, tools, and analytics that support the operational and developmental environment that will enable our sustained maritime dominance,” according to a memo signed by CNO Adm. Mike Gilday. But little has been done to formally ensure that unmanned technologies and their critical enablers would be developed and fielded in tandem.

Navy and Marine Corps leadership vowed to give the attention needed to ensure the whole package – the unmanned vehicles, as well as the spare parts, the operators and analysts working with the unmanned systems (UxS), autonomy technologies, resilient communications, payloads and common interfaces, power and endurance, reliable mechanical systems and more – is fully funded and delivered.

“The complexity of warfare is driving us to manage this at a different level. Navy Integrated Fire Control Counter Air (NIFC-CA) is one of those examples where I have to align all those programs at once,” Kilby said during the call with Smith and acting Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition Jay Stefany.

“When Secretary Stefany has gate reviews now for platforms, we bring in the enablers, the managers of those links, to make sure they’re pacing and going to deliver with that platform,” Kilby continued. He said manned-unmanned teaming will require that not just one program from its program manager be fielded successfully, but rather that the Navy create a warfighting capability where “many programs are reliant on and contribute to that capability, and we’ve got to make sure that we’re aligned to that.”

Though Stefany, Kilby and Smith said during the call that they were confident they could manage this inter-connected acquisition and fielding effort through high-level leadership and focus, a prominent House Armed Services Committee member expressed both optimism and concern after the Navy released the unmanned plan today.

Rep. Rob Wittman, the top-ranking Republican on the HASC seapower and projection forces subcommittee, said in a statement that “unmanned systems are here to stay and will continue taking an increasingly prominent role, providing the flexibility our Navy needs to fight and win the wars of tomorrow. It is exciting to see this process underway, but we must focus on getting this right rather than doing this too quickly. To get this right, we must resolve the technical and operational issues with a few of these vessels before entering full production. If that sounds commonsense, it is.”

“Yet, we have been here before, rushing into the full development and production of a promising new platform too soon. It always proves a costly mistake, and we cannot afford to make that same mistake again,” he continued.

“We must work out these new platforms’ required capabilities and operational concepts before they enter full development. Simply put, the Navy must show they can meet the critical milestones and understand these platforms’ roles before we invest taxpayer money into the vessels’ full production.”

Kilby pointed to land-based test sites to demonstrate reliability and the iterative process for drafting and continually refining concepts of operations as reasons for lawmakers and other stakeholders to have confidence that the Navy can learn quickly so it can overhaul the fleet and reach its manned-unmanned teaming vision quickly.

“Working together, the three of us here today are committed to pursuing, developing and integrating unmanned systems into our future force structure,” Kilby said.