At the beginning of the year, the Navy and Marine Corps sent a new fleet plan to Pentagon leaders that called for relying on smaller ships and unmanned vessels to meet future missions and defeat future adversaries. The Pentagon rejected the plan.

Nine-months later, Pentagon leaders reached the same conclusion: the Navy needed to be more distributed and weighted towards small combatants and unmanned craft.

What did that additional effort really get the sea services? Not much, according to some officials involved in both processes.

The Navy and Marine Corps spent the bulk of 2019 working on their first-ever Integrated Naval Force Structure Assessment that took both service’s anticipated operational needs into consideration when developing the future fleet. That INFSA and an accompanying long-range shipbuilding plan were never released and likely never will be, as they were absorbed into an Office of the Secretary of Defense-led Future Naval Force Study effort that used the INFSA as one of three inputs to determine the future fleet design.

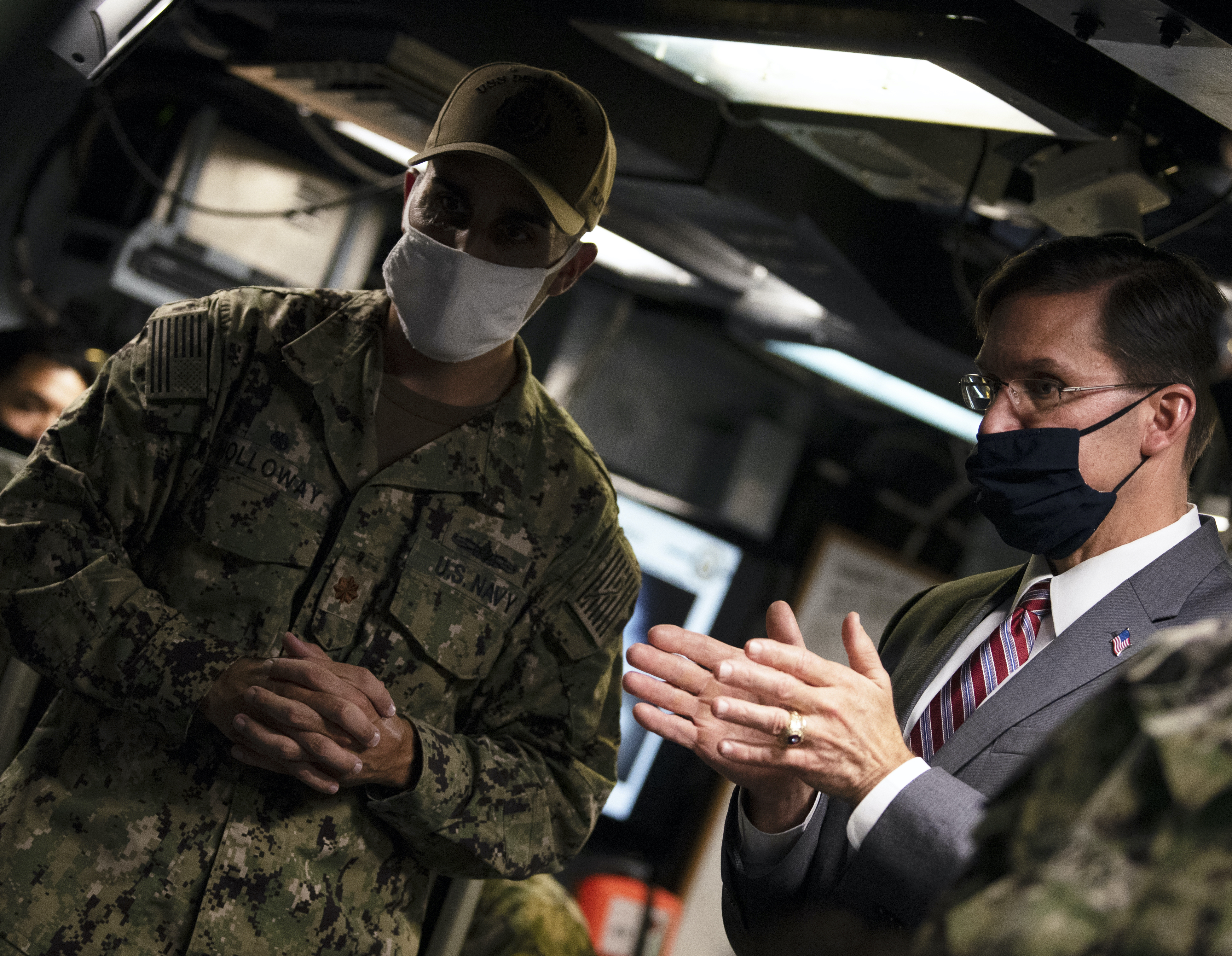

The OSD effort ended last month with the announcement of Battle Force 2045, a 500-ship fleet of manned and unmanned ships that would be fielded in the next 25 years. Defense Secretary Mark Esper has discussed the plan several times in public remarks but still has not released any documents outlining the plan – or, importantly, how much it would cost to build and sustain.

Compared to this 25-year plan to reach a 500-ship Navy, former Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly told USNI News last week that the original Navy/Marine Corps INFSA actually laid out plans to get a fleet of about 450 manned and unmanned craft in a much shorter timeline – in 10 years instead of 25 – and that, if extrapolated out another 15 years to match OSD’s timeframe, the INFSA could easily have hit 500 ships by adding more small combatants and unmanned vessels.

“In the traditional battle force ship numbers, we were hovering up to 380 or something, and then when you add in all the unmanned stuff it was going to be 430, 450, something like that. And that’s why when I hear stuff like the 500 number now, I guarantee you the difference between that number and the number we were thinking about back then is just the number of unmanned systems. That’s probably where the delta is, in my opinion,” Modly told USNI News in a recent phone interview.

Modly served as acting secretary while the INFSA was undergoing final wargaming and presentation to OSD and when OSD made the decision to conduct its own effort instead of releasing the INFSA to lawmakers.

“That was always going to be what was in the margins: it’s going to be the unmanned stuff, it’s going to be the number of small surface combatants we can build in that amount of time.”

Modly said the Navy looked at a 10-year window for several reasons: first, he said the Navy had done little to accelerate growing the fleet when it previously planned to hit its 355-ship goal in the late 2030s, and so he wanted to hold the service’s feet to the fire by putting a shorter timeline on the effort. Second, he said 10 years is a “strategically relevant timeframe” and that past efforts to look farther out “had no basis in budget or strategic reality.” Finally, budget uncertainty in the outyears, combined with the fact that the Navy has zero program-of-record frigates, unmanned surface vessels or unmanned underwater vessels in the water today, meant that there wasn’t much of a point in quibbling over how large those fleets could grow between 2030 and 2045.

On the small combatants, he said, “that’s going to rely heavily on the frigate program and whether they can get up to building more: right now they’re building, the pace was two to three a year, and the question was can we get up to more than that. And in order to do that, you’d probably have to get a second source of supply to do that, a second shipyard to build them – but the Navy wasn’t going to do that until they knew the frigate design was good and it was operating well and then would probably open it up.”

On unmanned, “we didn’t have enough experimentation, enough experience with these unmanned vessels, and so we needed to just be honest: we think we’re going to need these, we think we’re going to need them somewhere in the range between 50 and 75 of these, or 75 to 100, but today that number is sort of irrelevant because you just had to get going. You had to get going in driving down that path, and I was pushing for sort of an iterative process that would constantly be updating these numbers.”

When Esper and his office expressed concern, Modly told USNI News, “my point was, you can go ahead and spend another nine months and study this stuff to death, but it doesn’t matter – what you really need is a national mandate to grow the fleet, and by putting this off by another nine months, you’re going to miss a budget cycle, you’re going to miss the opportunity to convince Congress, get allies aligned, start talking about it and try to convince the American people that it’s important and why it’s important. And he just didn’t want to do that. So here we are.”

Elsewhere in the fleet, Modly said he and the Navy was considering 10 to 12 carriers – 12 is the congressionally mandated floor, but current shipbuilding plans don’t show the Navy getting there until the 2060s. Dropping to 10 would free up some funds, which Modly said could be invested in ship maintenance and help keep the 10 carriers at a higher state of readiness and deployability. Esper’s Battle Force 2045 has a range of eight to 11 instead, using some of the savings from the nuclear-powered carrier fleet and investing it into light carriers to supplement them.

On large combatants, Modly said the INFSA would have lowered the requirement from the previous goal of 104 to something in the 90s. OSD was looking at a figure in the 80s, he said. Modly would not discuss exact numbers with USNI News, since the INFSA was classified when he left the Navy in March. He said he has not been in touch with Navy or Pentagon officials since his departure.

INFSA did have some number of light amphibious warships and small logistics ships for the Marines, Modly said, though the numbers were likely lower under INFSA compared to Battle Force 2045 due to the 10-year versus 25-year timeline; the Navy does not currently have either ship class in the fleet, and it would take a couple years to design and contract for these ships, let alone start building them.

Overall, Modly said, what he’s heard of the Battle Force 2045 plan is just an extrapolation of the Navy and Marine Corps’ INFSA, stretched out over a larger timeframe.

At their core, he said, the two plans get after the same concern: the “highly concentrated cost per vessel that we have. It had climbed – when they built the 600-ship Navy under (former Navy Secretary John) Lehman, the average cost per hull in real dollars was about a billion dollars per ship. And now our average cost per hull is about $2 billion a ship in real dollars. So what we’ve done is, we’ve concentrated a lot more of our expense and firepower on a fewer number of platforms, and I think the analysis started to show that that made the fleet more vulnerable. So the premise of our study, of the [Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office] study, of some of the stuff that was done out in town, was, how do we move to become far more distributed, far more agile, far more adaptable and unpredictable?”

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the Navy’s deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), has been central to both the INFSA and the Battle Force 2045 efforts. He has said little publicly about the force designs or how they compare. However, last week at a virtual event cohosted by the U.S. Naval Institute and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, he confirmed what Modly said: that the bulk of the difference between the plans comes down to the timeline.

“The farther you go out in the future, the less sure you are of what it’s going to be. So we had different expressions of what we thought red could be, and we had different expressions of what we thought blue could be, but I think it’s consistent with what we’ve talked about in many forums where we had a more distributed force,” Kilby said.

“We looked at some specific platforms and said, wow, they’re as impactful as we thought they were. We looked at other elements of our fleet – our amphibious force structure – and said, hey, we probably need some new elements here to help us with expeditionary advance basing operations or littoral operations in a contested environment,” he added, referring to the light amphib and small logistics ship that appears in both INFSA and Battle Force 2045.

“What was most healthy, from my view, of the interaction was this ability to step back and question, and not be my answer versus your answer, but, let’s look at this answer together,” Kilby said.

Bryan Clark, a senior fellow and director for the Center for Defense Concepts and Technology at Hudson Institute – which developed the third input in the OSD effort – told USNI News that the difference in the timelines was actually more significant than Modly suggested.

For Clark, the threat China poses in 10 years may be greater than it is today, but the Chinese threat is greater still when projected out to 25 years. As a result, the force that Hudson recommended was based on the greater Chinese threat rather than the more moderate Chinese threat – and with that threat picture in mind, the Navy and Marines could start rebalancing the force more aggressively today to get ahead of the threat, in case China advances faster than expected.

Clark agreed that, based on his knowledge of the three inputs to the OSD effort, the three plans moved in the same direction – essentially shades of the same color. But he said it came down to “a matter of how aggressively you rebalance the fleet,” and that Hudson recommended – and Esper agreed – that the rebalance had to happen faster: more light amphibious warships, more small combatants, more small logistics ships and more unmanned craft, on a faster timeline.

Clark explained there were two imperatives for this more aggressive rebalance. First, if China becomes more lethal on a quicker timeline, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps would be ready. Second, the end state of a more distributed fleet that relies on smaller ships would cost less to sustain and operate, and getting to that vision faster would carry a smaller overall bill.

Clark said that, while the Navy seemed to be headed in the right direction in its INFSA, it was making the changes based on how the fleets wanted to operate in the future, in line with new Distributed Maritime Operations and Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment concepts. When Esper and OSD rejected the plan, Clark said, it was likely because they were less concerned with fleet concepts and more worried about the Chinese threat and the overwhelming bill associated with building and sustaining a larger Navy fleet. Both sets of concerns led to future fleets with similar underlying principles, Clark said, but with OSD taking a more aggressive approach to get there faster and to take the vision farther.

Still, Modly said he’s not convinced there’s a significant or practical difference between the two.

“My entire push was that we needed to get to a bigger navy within 10 years,” Modly said.

“Their whole plan is a 25-year plan. So to me it’s like, beyond five years, look at the budget for that: they say, how are you going to pay for that? You look at the budget for five years, it’ll be a steady, steady slow climb, and then all the sudden they’ll project that all the sudden they’ll get all this money in that next 20 years. And so, it’s nonsense.”