The Navy and Marine Corps basic training commands are unsure if they’ll have enough money to finish out the fiscal year, due to costs incurred from COVID-19 prevention measures they’ve implemented – but they’re going to keep doing what they’re doing because it’s allowed training to progress without the coronavirus having much of an effect, officials say.

In fact, the current system – future sailors and Marines go through a 14-day restriction of movement (ROM) period just outside their boot camp’s location when they first arrive, are tested for COVID-19 at the end of the two-week quarantine, and if they test negative they’re allowed to start basic training with social distancing, face coverings and increased hygiene required – may be a fact of life for at least another year.

Both the Navy and the Marine Corps saw early pauses in recruits being moved to basic training, as well as temporary measures to slow or stop movement of recruits from states that were considered hot spots in the pandemic. But today, movement of new recruits to the Navy’s Recruit Training Command in Great Lakes, Ill., and the Marine Corps Recruit Depots in San Diego and Parris Island, S.C., is mostly unimpeded.

Marine Corps Training and Education Command Maj. Gen. William Mullen told reporters today that the number of recruits in each company is limited due to the number that can fit into a squad bay with social distancing measures in place: companies at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego are limited to 325, and at MCRD Parris Island it’s 454 for males and 120 for females due to the different ways the barracks are designed.

But, Mullen said, the Marine Corps had built some weeks into the schedule where no new recruits were shipped, just in case the Marine Corps found itself needing to address an outbreak or ran into problems moving Marines throughout the training pipeline. No real problems have arisen so far, he said.

The Marine Corps was supposed to get 38,000 new Marines through basic training this fiscal year, and the service is on track to come up short, but not as short as they previously thought.

“We left a number of open weeks between now and the end of the fiscal year, just a couple of them, just in case things don’t go well with regards to the measures we’ve taken with regards to COVID. Things are going very well, so instead of this week being an open week, we shipped (recruits to the depots) – so that’s less Marines we’ll be short,” Mullen said.

“We have all the recruits we need in our pool, it’s just a case of putting them through the squad bays.”

Mullen would not say how many recruits have shown up at San Diego or Parris Island with COVID-19, but he said, “for the recruits that are showing up, we’re having very, very few test positive.”

On the Navy side, more than 8,100 new sailors have been sent to the fleet during the pandemic, and the service is on track to meet its accession goal of 40,800 new sailors for Fiscal Year 2020, Rear Adm. Milton Sands, commander of Naval Service Training Command, said during the same media call.

In fact, 6,700 recruits are engaged in basic training today, and the Navy recently increased its weekly shipping to 1,200 a week – the most since the pandemic hit the U.S., and up from the 500 sailors a week the Navy dropped to while working out its testing and social distancing plans in the beginning.

“We’ve been able to make this increase and continue training throughout the pandemic using a combination of risk-mitigation procedures to protect our force and continue our mission,” Sands said during the call.

On the officer side, 1,100 new Navy and Marine Corps officers were commissioned this spring, he said, and 710 new active and reserve officers have finished training in Newport, R.I., and gone out to the fleet since March.

Asked about the cost of keeping this all up – housing the recruits during their ROM period, paying for the masks and cleaning supplies and other items that allow for training to move ahead at this pace – Mullen and Sands said a supplemental funding bill from Congress helped but that they needed to make these costs more sustainable for the long haul.

“Right now it’s a bit of a moving target” as to whether the recruit depots would finish the fiscal year within budget or not, Mullen said.

“We obviously had the COVID supplemental, that’s been very helpful. We got to a point where we’ve normalized what we’re doing for ROM, which is probably the most expensive part of this because that goes to the additional housing piece there. And what we’re trying to do is find a less expensive way to do what we’re doing now. We’re hoping to be able to [reduce] how much money we’re spending on COVID protection measures, but that again, moving target.”

Several Marine Corps offices reached by USNI News could not elaborate on specifically how much the Marine Corps was spending to house the recruits now during their ROM or what options the service may have to lower that bill.

The Navy has been putting incoming recruits at local hotels and even a Great Wolf Lodge water park outside Chicago. Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Adm. John Nowell said recently that the hotel bill comes to $1.1 million to house 500 recruits for two weeks prior to their training. The service is in talks with the National Guard regarding potential facilities to house incoming recruits.

“The COVID supplemental has been immensely helpful in maintaining our ability to produce sailors for the fleet. By far the most expensive part of this for us is paying for our off-site ROM facilities, and as Gen. Mullen mentioned, we too are engaged in looking for a cheaper and longer-term sustainable option. And we’re starting to look now at a base to the north of us that we can use that will simultaneously reduce our cost for force protection and allow us to have one location to execute this off-site ROM for what we think may be a period of up to a year. We’re looking at this over the long haul,” Sands said.

Despite the cost, Mullen and Sands made clear that they’re meeting their commitment to the services by producing well trained new sailors and Marines while keeping the recruits and the training staff as safe as possible during the pandemic.

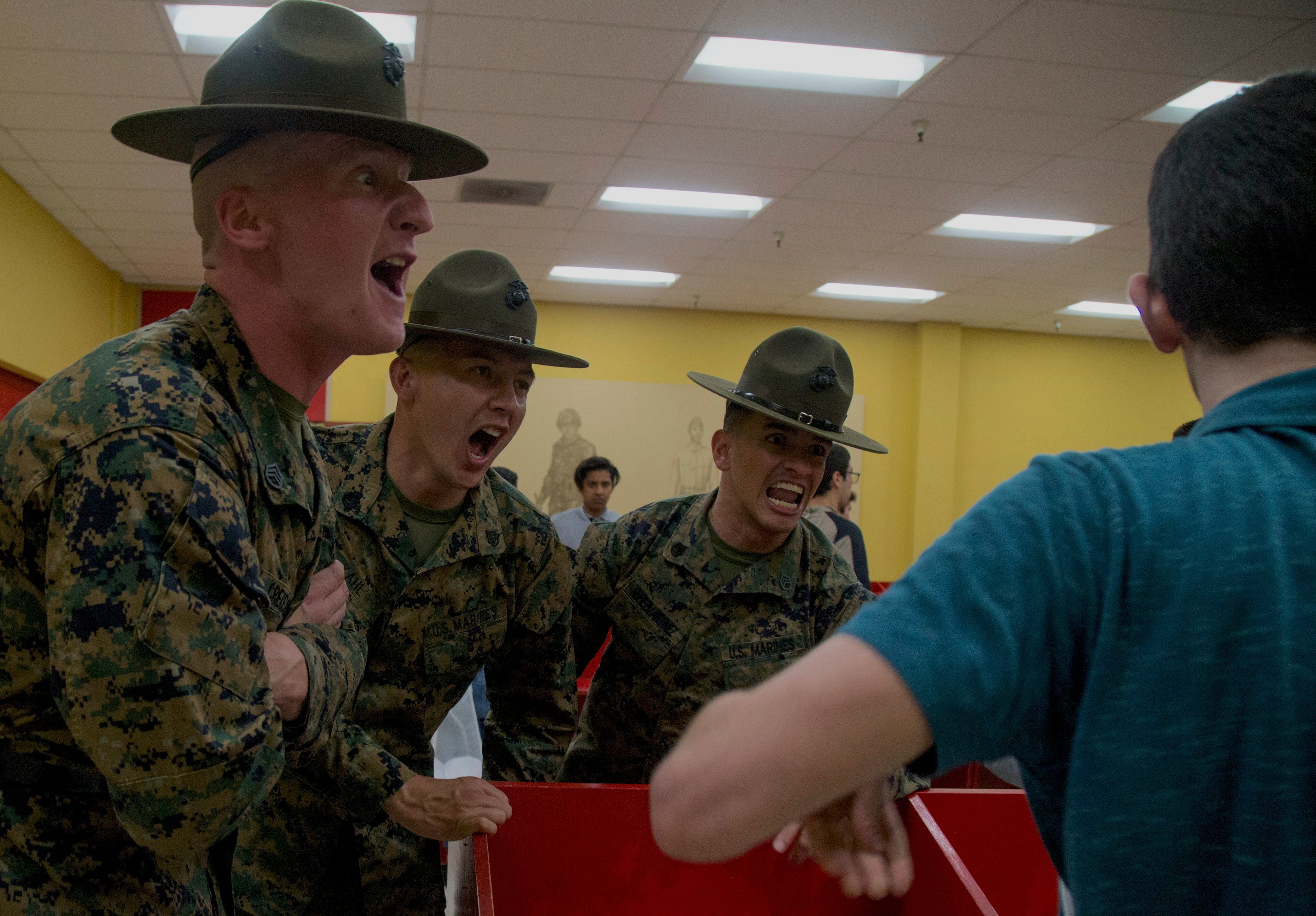

“No training standards, program instructions or graduation requirements are being altered or reduced,” Mullen said. And with about 30,000 Marines going through some type of TECOM-sponsored training during the pandemic and less than 500 of them testing positive for the virus – many asymptomatic, and none requiring hospitalization – “we have had people obviously get it, but it’s mostly been a non-event for us.”