WASHINGTON NAVY YARD – The Navy officer who took a manned submersible to the deepest part of the ocean in 1960 said it would have been impossible without the steady financial support by the Office of Naval Research for oceanographic research.

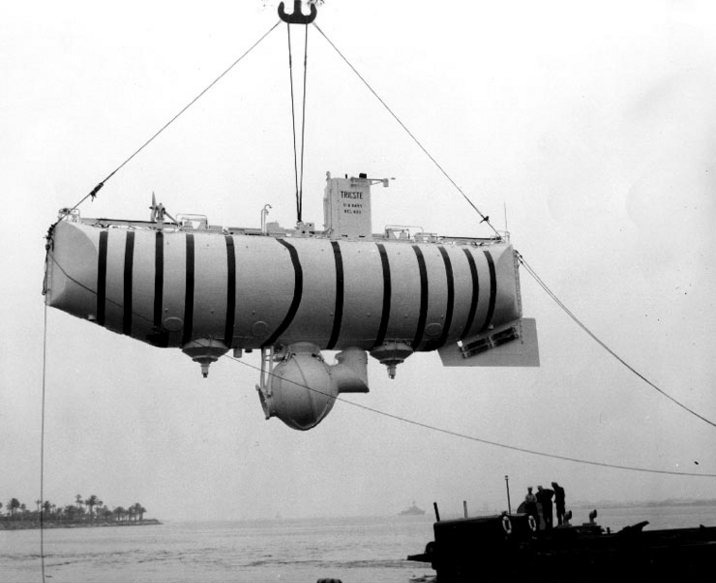

“ONR was generous to a fault [and] is underappreciated for this whole thing,” with the command buying the bathyscaph Trieste from Swiss inventor and scientist Auguste Piccard in 1957 and staying with the project over the years, Capt. Don Walsh said at a ceremony at the Washington Navy Yard commemorating the 60th anniversary of the dive to the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Walsh was assigned to the project in January 1959 and remained there until 1962. “I was looking for interesting things to do” as a young lieutenant in 1959 and not “fly a steel desk” in an office in San Diego.

The record-setting dive of almost seven miles into the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench was “a demonstration of the human desire to explore,” said Capt. Matt Farr with ONR during the ceremony.

Details of the dive remained tightly held in the lead up to the attempt, Walsh said. Then-Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Arleigh Burke didn’t want any more bad publicity for the service after the failures of the Navy Vanguard rocket program in the late 1950s ahead of the Soviet Sputnik launch.

“The Cold War was on; who was better?” – the Soviet Union or the United States, Farr said. “There was a push to be first” in everything, but on this mission, everyone was to keep their mouths shut. There were 14 men – two officers, five sailors and seven civilian technicians or scientists – assigned to the project conducted by the Navy’s Electronic Laboratory in San Diego.

Trieste’s dive and the events leading up to it were “very different” from the “massive publicity campaign for manned space” that followed the naming of the first seven Mercury astronauts, retired Rear Adm. Samuel Cox, the director of Naval History and Heritage Command, said on Thursday.

Walsh told the audience of several hundred that the Jan. 23, 1960, dive into the Mariana Trench, about 200 miles off Guam, was “be the ultimate test of this platform, not an adventure.”

Since the dive occurred in the shorter days of winter, Walsh said the dive was to last no more than nine hours. This would give the scientists and sailors working aboard the tug that towed the bathyscaph into place enough light to do their jobs safely. Seas were rough ahead of the attempt.

Trieste and the upside-down steel “balloon” it rode under was “not designed to survive wind and waves,” Farr added. The “balloon” was filled with aviation fuel to give it buoyancy.

As Walsh and Piccard made their final preparations for the descent, a message came through to the destroyer escort operating with Trieste to scuttle the mission. However, instead of passing the message along, it was pocketed. Walsh and others compared that move to Horatio Nelson holding a telescope to his blind eye and seeing nothing to contradict his original plan of attack at the Battle of Copenhagen.

The answer back was, “Trieste is at 10,000 feet.”

Likewise, when Walsh and Piccard heard a loud crack on an earlier dive coming from the rear viewport, Farr said, “if he had decided to turn around [then], they may not have had another chance” to set the record. “Sometimes, you just have to decide to keep going.”

The repairs to the bathyscaph were made from what was available, including necessary fixants and straps from an auto supply store. “It was all done out of view of Piccard and our masters at the laboratory,” Walsh said.

In a telephone interview with USNI News before the event, Walsh described the dive as “just another day at the office,” though longer than other dives in time and distance. The descent took about five hours. Walsh stressed this was not a scientific mission. As before, he and Piccard were to test the safety of the vessel and gauge its performance, although it was not very maneuverable. As it descended and on the floor, it was barely able to move feet. “There were certain things you had to do” before the descent and after. They had been working “to kind of eliminate all the variables” to “take the unknown out of it.”

Nonetheless, there “was an element of risk,” Cox said at the ceremony. He added it was the “shiver me timbers” risk of failure with water pressure reaching 15,000 per-square-inch on the outside of the vehicle at those depths.

By the time Trieste surfaced, wave heights had risen to 20 to 30 feet.

At the event marking the opening of a major exhibit on underwater exploration at the museum, Walsh said he’s most frequently asked about the risk. The second most common question asked is, “what did I see?”

While the Mediterranean is murky, Walsh said the viewport allowed them to see “the rich biology of the Pacific, [looking] like minestrone soup,” at relatively shallow depths, Walsh said. “We had lights,” but they weren’t turned on to better view what was outside.

“The bioluminescence [from the fish] was pretty entertaining, like a reverse snowfall. You’re moving and they’re not.”

As they neared the seafloor, Trieste’s bottom reflectors lit up the view. Piccard first saw what they believed to be a fish, about a foot long, but the vehicle was kicking up so much sediment that all they could then see was “like white paint.”

Instead of settling down, for the 20 minutes Trieste was at depth, the sediment kept rising. The 16 mm movie camera and Hasselblad still camera they brought aboard were useless under those conditions.

Since the dive, the vehicles and the technology to support these underwater missions have leapt far ahead technologically. Walsh recommended checking out Victor Vescovo’s upcoming Discovery Channel documentaries on his recent dives into the Mariana Trench to see what life forms exist in the deep ocean.

Although Walsh accompanied Vescovo and James Cameron, the filmmaker whose credits include Titantic and Avatar, on their expeditions, he said he “didn’t want to be taking up a seat that should be taken by an oceanographer.”