THE PENTAGON – The timeline for fielding several major ship and weapons programs has been bumped up to “as soon as possible,” the chief of naval operations said, to counter Russian and Chinese military modernization.

Adm. John Richardson released an updated Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority 2.0 strategy document on Monday, which features admittedly aggressive acquisition timelines, he told USNI News in an interview today.

Whereas the original document he released in January 2016 called for “high velocity learning” – which encouraged the Navy acquisition community to try some new processes for designing, contracting and fielding programs like the MQ-25A Stingray on a tighter timeline – Richardson said the updated Design 2.0 now expects that that learning will lead to faster and cheaper acquisition going forward.

“Embedded behind all these pretty aggressive acquisition goals is the fact that we learned how to do acquisition different” since the 2016 document was released, Richardson said.

“And the elements of that are, let’s get our requirements team talking to industry earlier so that we understand, where’s the technological maturity, what can we achieve with confidence now?”

Richardson’s intentions pair a drive to move faster – ditching arbitrary initial operating capability (IOC) dates for an “ASAP” mentality – with a recognition that moving faster may require an iterative process that fields a good solution now and upgrades to a better one as technology matures.

“Things like the frigate, the large surface combatant – parts of that ship are going to last for the entire life of the ship: the hull of the ship, the power plant, the propulsion plant. But the rest of it is going to change very fast: the sensors and computing power and weapons even. It’s got to be designed into the ship to be able to swap that capability out quickly. And so that also gives us the confidence that we can converge on a pretty good hull form, build as much power into the ship as we can afford – it’s almost like memory for your computer, you’re going to use it all and want more – and then the rest of it’s designed to be rapidly upgraded through the life of the ship,” Richardson said.

The Navy will buy the first version of its next large surface combatant – a centerpiece of the Future Surface Combatant family of systems that also includes a small combatant and two sizes of an unmanned or optionally unmanned combatant – in 2023. That five-year contract, akin to the five-year contracts the Navy uses today for its Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, will be followed by another contract in 2028.

Though the Navy will have to move out on this large surface combatant in just four years, much is still unknown or undecided about this new ship. In August, Director of Surface Warfare Rear Adm. Ron Boxall (OPNAV N96) told USNI News that the Navy would not conduct an analysis of alternatives for the ship, but would rather start with the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer capability development document, have discussions with the fleet and with industry about how the next large surface combatant would need to be modified from that DDG-51 starting point, and then make decisions from there. The six-month window Boxall said he needed to make early decisions should be wrapping up next month.

Richardson said he’s not necessarily expecting that the 2023 design will be the “final” large surface combatant design, but instead would adhere to the idea of using an 80-percent solution today and iterating as technology advances.

“For the 2023 we’re going to have to converge on something that’s pretty well known right now. We’re not going to be able to meet that timeline and design some kind of brand new hull form. And I’ll tell you what, naval architecture’s been around for a while, so we sort of know how that works, so I’ve got a lot of confidence that we’ll get to something that will be perfectly adequate in 2023. Beyond that, who knows,” he said.

“So we’ll have the naval architects working in parallel, and so as these two streams move together, boy, when something’s mature enough – they say, holy cow, this is really going to be a lot more capable and also we can do this with confidence in cost and schedule – then we’ll just incorporate that it. So whether that’s at the next five-year mark or whatever it turns out to be, hard to say, but we’ll keep these things going.”

A key lesson the Navy learned over the past few years about cutting cost and time from acquisition programs is paring down requirements to the bare minimum. Richardson touted the MQ-25A program, which had just two key requirements: being able to operate from an aircraft carrier, and being able to refuel other aircraft. Richardson said this model can be applied to everything from the next fighter jet to the next large surface combatant, and he believes it is key to allowing industry to move faster and avoid unnecessary costs.

“The philosophical approach that we want to minimize the number of hard requirements allows a tremendous amount of creativity in terms of going to meet those requirements. So what happens when we come up with reams and reams of very, very specific requirements is that … certainly has implications for the design and may box out a really creative solution if we over-specify any particular aspect of the ship, the design. And it’s for ships, aircraft, submarines, what have you. And so we want to really minimize the number of hard requirements, bring industry into the conversation and give them as much trade space and freedom to innovate to meet those requirements,” he said.

Richardson’s document outlines many new acquisition programs in a short period of time – four surface ship classes by 2023, unmanned underwater vehicles as well as laser and hypersonic weapons by 2025 – but he said that the timelines are aggressive but well thought-out and analyzed.

“These aren’t just sort of random dates thought up on a late night. It was pretty carefully coordinated; each of these has been assessed and said, okay, well that’s aggressive but we can get there,” Richardson said.

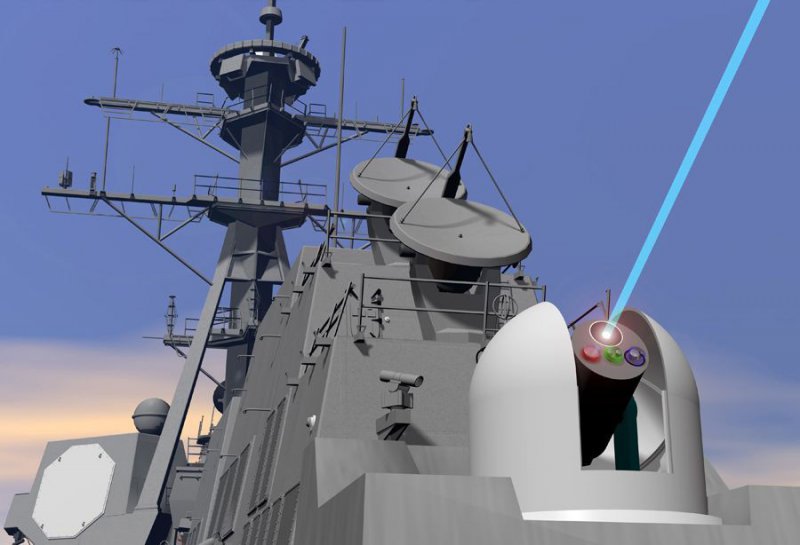

On the laser weapon system, the design calls for one to be fielded by 2019, with a family of weapons developed and fielded no later than 2025. A Laser Weapon System was used on afloat forward staging base USS Ponce (AFSB(I)-15) as a demonstration, but the Navy has not fielded an operational laser weapon yet. Similarly, industry has done some work on hypersonic weapons, but the Navy has not coalesced around a solution to be fielded by 2025, and Richardson declined to name which program was the main effort.

“We’re on track to put a high-energy laser on a ship next year. And then there’s the integration and all of that that we’ll learn very fast, and then it’ll just start proliferating around the fleet after that,” he said.

“And same with hypersonics, we’re moving very quickly in that area.”

Even on the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program, which has had a long-established requirement to complete the first-in-class boat by 2028 and have the future Columbia go on its first patrol in 2031, Richardson said he wants to see some acceleration and believes it is feasible with his ASAP mindset.

“One of the things that’s been a persistent goal in the Columbia program is to try and continue to buy [schedule] margin,” he said, to add a little cushion to the already-tight timeline for the program.

“If we buy enough margin that we can deliver the thing earlier, let’s do it.”

Richardson said that, though he included quick turnaround dates in his Design 2.0 document, he hopes the acquisition community and industry will be off to the races to field these new capabilities “ASAP.” He said there are often talks about making changes or otherwise slowing down a program, which is deemed acceptable as long as the program still meets its required IOC date.

By taking away IOC as a measure of success, “I hope that it puts all of us in a much more competitive mindset. What has emerged is a system that for whatever reason is really kind of internally focused, and is not really focused on winning in a competitive environment. And so just imagine the automobile industry, the smartphone industry: the second car that has a particular capability, the second smartphone that has a particular capability, that’s a significant disadvantage over the first to market. And it’s the same in military capability. So we want to make sure that we’re delivering this capability at a competitive speed. We are first on the water with the high capability and not the second,” Richardson said.

“So by saying, hey, look, let’s not build in an artificial date – that may give us comfort and slow down our pace. Let’s get competitive and race this thing, because that’s what great power competition means.”