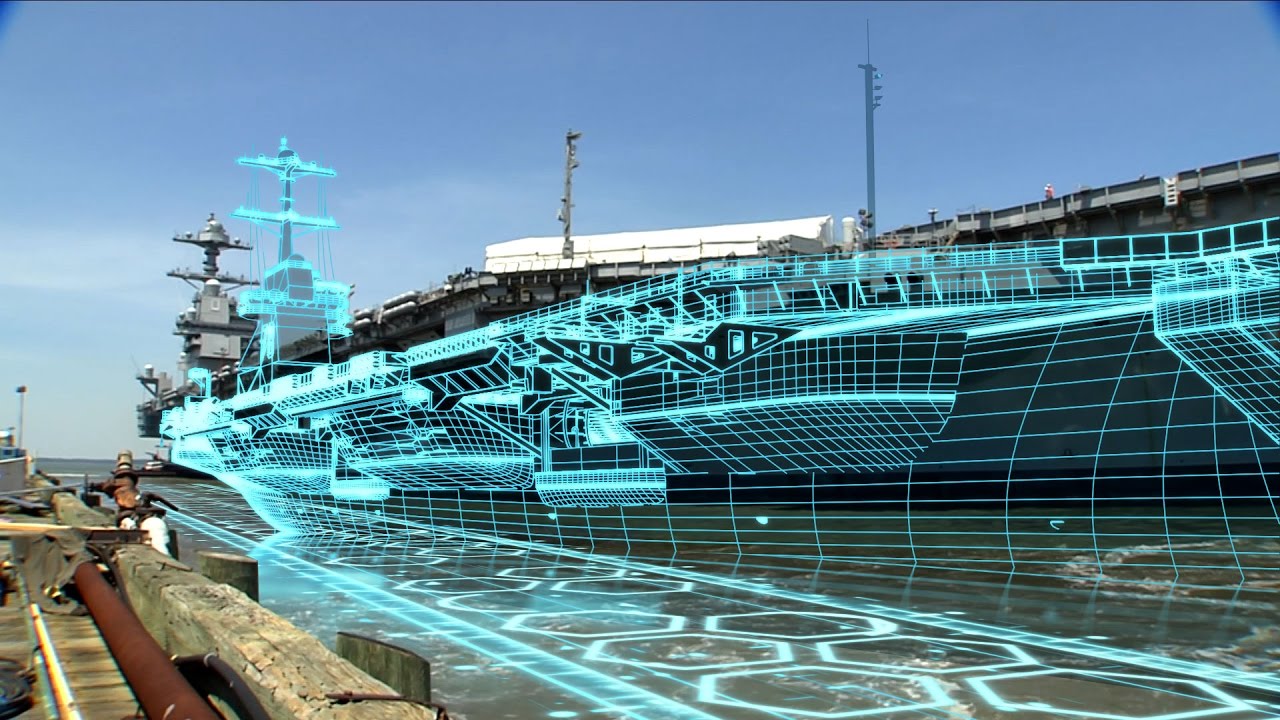

Now the Navy is looking to leverage that win and expand its use of laser scanners to not only cut down costs for aircraft carrier maintenance planning and execution but also tie into virtual reality trainers and other cutting-edge technologies.

In the case of the George Washington RCOH, a team of two or three engineers from Newport News Shipbuilding flew out to the forward-deployed carrier in Japan with a LIDAR scanner atop a tripod. As the tool slowly spins around it gathers millions of data points depicting how far away objects are from the scanner. The resulting 3D point cloud shows the precise location of items in the room – not where a server rack was supposed to be according to the blueprints, for example, but where it actually is.

Capt. John Markowicz, the in-service carrier program manager, told USNI News in an interview that the $1.8-million savings from that one ship check effort was about 15 percent of the total cost of that portion of the RCOH planning, and that his office was already employing the laser scanning technology ahead of the next RCOH for USS John C. Stennis (CVN-74). He said it was too early to guess a percent savings the laser scanning will yield this time around, but that it would likely be on par or better than with George Washington because Newport News Shipbuilding has continued to invest in the laser scanners and learning how to best leverage them.

Markowicz said the tripod-mounted scanners cost about $3,600 each, and smaller handheld ones for scanning small spaces cost about $600. The actual scanning service can cost between $50 and $250 an hour, and post-production work can cost $100 to $300 and hour. USNI News visited Newport News Shipbuilding last October, and during a lunchtime meeting a company engineer scanned the whole conference room and produced a point cloud model of the room within about 30 minutes, as an example of how quickly the scanners can work.

Maintenance mockups and interference detection

Once those point cloud models are created, the Navy and Newport News have already found several uses during the RCOH and other carrier maintenance planning and execution phases.

First, for the actual planning, the point cloud models can offer some spatial perspective that flat blueprints can’t, as well as an updated “as-is” assessment of the space instead of the “as-designed” view the blueprints contain.

Mark Bilinski, a scientist at the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Pacific and its Battlespace Exploitation of Mixed Reality (BEMR) Lab, and his team are working on laser scanning technology and ways to leverage the 3D point cloud product. He showed off some of the technologies to USNI News during the U.S. Naval Institute and AFCEA’s WEST 2018 conference in San Diego in February. During a panel presentation at WEST, he said that sometimes the 3D scans just show discrepancies between where an item was supposed to be installed versus where it actually was installed. However, he ran into a case where the blueprints depicted an escape hatch of a certain size, but it was larger in reality; in that case, a planner might have thought there was room to install something nearby, when in reality putting the equipment there would actually partially block the hatch and cause a safety issue. In another case, the blueprints showed a hatch as being much larger than it actually is, and so the planner might have thought the space was unusable.

“That’s an opportunity cost because that might be some space that you could use for an install that you don’t think is available to you,” Bilinski said.

Once the planning is done and execution is set to begin, Markowicz said the 3D models, unlike 2D blueprints, can help identify interferences and obstructions, help find the best route down narrow passageways for bringing in bulky equipment to install, aid in laying in pipes and wires and more.

“That is valuable, it cuts down time in the shipyard,” which ultimately cuts down cost and allows the next carrier to come in for maintenance quicker.

Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility are beginning to embrace this technology, which could spread to the other two public shipyards to support submarine maintenance activities too, and Newport News Shipbuilding is “all in” on the private sector side, he said.

Markowicz noted that taking the scans and making mockups in a 3D digital environment can not only save time on major efforts like finding the best routing for piping, but can also help with little things – for instance, there was a case of trying to install a laptop in a phone booth area, but it turned out that the laptop couldn’t open all the way without hitting the phone.

“We stumble upon these things sometimes a little late in the design process, or actually the install process. It’s not as efficient as it can be,” he said.

Every time a maintenance or modernization activity takes place, the scan would become slightly outdated, but Markowicz said the idea would be to rescan periodically and maintain records of all the scans as “selected records” that accompany the 2D drawings for the Nimitz class today.

“Once we have this digitally, I think that’s pretty useful. We can share it with multiple activities and have the documentation for future use and future availability planning,” he said.

Bilinski also noted the ways laser scans could help during a major maintenance period, when multiple program offices are trying to get their own equipment in and don’t always have a great way to coordinate.

In many availabilities, Bilinski said, someone goes to install a piece of equipment in a space, only to find that that space is taken. Instead, he will just take the next closest space that meets his need. Then the next person comes in to use that space and finds that it was just taken, causing a cascading effect. If everyone involved in the maintenance period were working off a shared digital plan that could be updated in real time as systems were installed, conflicts could be identified sooner and plans could be rearranged as needed without any on-ship confusion.

“If you have that collaborative environment where everyone is planning off of the scan data, the installer can see not only that this space is physically available, but hey, it’s also available in the planning environment; no one is planning to put anything there. Or, maybe someone is planning to put something there but you’ve got to put your equipment somewhere, so you put it there, but you at least know who to notify so that we can start fixing this problem earlier than discovering it when the next program office shows up to install their equipment,” he said.

Virtual reality application

Virtual and augmented reality tools are already changing how ships are built, with Newport News Shipbuilding telling USNI News during the October visit that the use of VR goggles while laying pipes and cables for the future John F. Kennedy (CVN-79) has cut the required man-hours in half. Newport News is also sending its shipbuilders out with tablets that can use VR to show what’s on the other side of a wall or where to cut a hole into a wall, and can also include how-to videos to show step-by-step how to do the day’s tasks.

Markowicz said there would likely be less applicability for that technology on the ship repair and maintenance side compared to the ship construction side, but he hopes to explore how the public shipyards can use VR and tablets to drive efficiency up and cost down.

Where VR and laser scanning could converge, though, is on training. Because each ship has a different set of navigation and steering systems, surface search radars and other systems, allowing a sailor to train on his or her own ship is more useful than training on a generic ship. Markowicz said his office is working with Bilinski’s BEMR Lab to create ship-specific VR training tools for while ships are in maintenance. They scanned destroyer USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) after its collision last year, and while the ship undergoes a lengthy repair process, sailors could use VR goggles to practice maintenance and repair work on McCain’s specific configuration without having to actually be on the destroyer. The BEMR lab already has Virtual Eqiupment Environment (V2E) tools that let the user walk into a room, spot a server rack, for example, and begin to take apart and put back together the server rack.

Similarly, when a carrier is in RCOH for four years, sailors are often times flown around the world to get training time on other carriers. Though the ship is safe for them to be in while in RCOH, the systems are all ripped out. If the Navy had scans of the last carrier that came out of RCOH and could insert a finished product view into VR goggles, sailors could train on their own ship at Newport News while the RCOH goes on around them.

“We’ve got to find creative ways to do training. Normally they leave … and they go out to the fleet and ride another ship and get their training that way. But a lieutenant had the idea of, okay, you can go up to pri-fly (primary flight control), any everything’s ripped apart but you can put on these goggles and see what your space is going to look like 48 months from now … and visualize it all and stand there in your space without having to go to another ship,” Markowicz said.

“I definitely see a partnership with the BEMR Lab and laying that out for training for ship’s force, closing that gap in readiness. Because I was part of the Carl Vinson (CVN-70) overhaul, and our skills atrophied as we stayed in overhaul for that length of time. So we have to find opportunities to sharpen our skills.”

Bilinski said there could be other uses for combining a current ship scan and VR goggles or tablets. For example, if scans of ship spaces were taken correctly, they could be woven together to create essentially a Google Maps of sorts. New sailors could use it to learn their way around the ship. Or, more importantly, “let’s say a fire breaks out on a ship and you need to go into a compartment and fight that fire – it’s going to be smoke-filled, it can be dark, you may not have ever been in that space, there could be plenty of places where you can fall, you could twist your ankle, you could bump into equipment in the space. If you were to understand where you were, you could look through that wall and see what the last as-is condition of the ship was and sort of get an idea of what you’re getting into before you go into that space,” then firefighting or other emergency response efforts could be done potentially more safely and quickly.

Policy and technical barriers

Much like other emerging technologies, Markowicz said those trying to implement laser scanning are facing the usual set of challenges: how does the Navy balance the need to ensure technical rigor while also not being too proscriptive and excluding potential scanners or data formats that could be useful? What legal and ethical concerns need to be addressed through policy changes?

“That’s the rub right now,” Markowicz said. “You see us working with Newport News. I’m sure there’s other pockets within NAVSEA that are working on it. But alignment across the whole NAVSEA equities hasn’t happened yet. So where we are successful at NAVSEA (Naval Sea Systems Command) is where we have a singular tech warrant holder who owns turbines or fire protection or what have you. So we’re really successful in employing that model across NAVSEA. I see a vision someday where you have a tech warrant holder for a laser scanner that’s able to establish standards, policy, requirements to go forward and articulate that to industry.”

His team is hosting a laser scanning summit later this month to identify barriers and develop courses of action to begin to address them – everything from how many dots per inch are needed for the scan to be useful, to, are there any engineering decisions that cannot or should not be made based on laser scanning and 3D point cloud modeling work. Markowicz suggested that anything related to the nuclear propulsion system is going to require much more technical rigor than other parts of the ship, but he said he still sees great potential for savings with laser scanners beyond what the Navy and Newport News Shipbuilding are doing today.

“I think across the board we will save money, and in that way the leadership is behind it if it helps us be more efficient,” he said. Back when the Navy and Newport News first did the George Washington ship check, then-Navy acquisition chief Sean Stackley’s message to Markowicz was, “I absolutely needed to make it my mission to leverage new technologies and be more efficient in the repair business,” the captain said, and he believes this is a prime example of how to do that.

To be successful enterprise-wide, he said, “I think the real key is setting the standards, which will provide a framework where contractors and Navy can plug into. To get there, we need to provide technical leadership, host conferences … flush out all the issues. At least create a standard so that we can contract and have deliverables. One software package or one laser scanner, I don’t think we need to be that proscriptive. I think we set a standard for industry, like an ISO standard, and people will come around to it.”

He likened the point cloud image to a PDF that could be opened on a Mac or a PC and is readily sharable among users, and said it would be important that, regardless of what scanner is used, the output has these qualities too. He suggested that some scans would need to be precise while others could forsake precision for speed if the user just needed a general idea of how a room is laid out, and all those types of issues would eventually become written out and standardized.