The wreckage of USS Helena (CL-50), the WWII-era St. Louis-class cruiser that survived the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and played an integral roll in defending Marine Corps operations in the Battle of Guadalcanal, was discovered last month by a team of researchers financed by billionaire philanthropist Paul Allen.

Helena was sunk early in the morning of July 6, 1943, after being struck by three Japanese torpedoes during the Battle of Kula Gulf. Allen’s team found the ship resting on the sea floor about 2,821 feet below the surface, in the New Georgia Sound off the coast of the Solomon Islands, according to a blog posted Wednesday to Allen’s website.

Helena had been engaged with Japanese forces since the first moments of U.S. involvement in WWII. Within minutes of the first Japanese bombs dropping on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Helena was struck by a lone torpedo that passed under a minelayer moored next to the cruiser, according to Naval History and Heritage Command.

One engine room and one boiler room were flooded and wiring to the main and 5-inch batteries was severed. Within 2 minutes of being hit, though, the crew brought the forward diesel generator up, providing power available to all mounts. The crew’s actions, a combination of sending up heavy fire and performing quick damage control, was credited with keeping Helena afloat, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Less than a year later, Helena was at sea, supporting the Marines landing at Guadalcanal.

“Helena, equipped with superior radar, was first to contact the enemy and first to open fire at 2346. When firing had ceased in this Battle of Cape Esperance in Iron Bottom Sound, Helena had sunk (Japanese) cruiser Furutaka and destroyer Fubuki,” according to the Naval History and Heritage Command, on October 10, 1942.

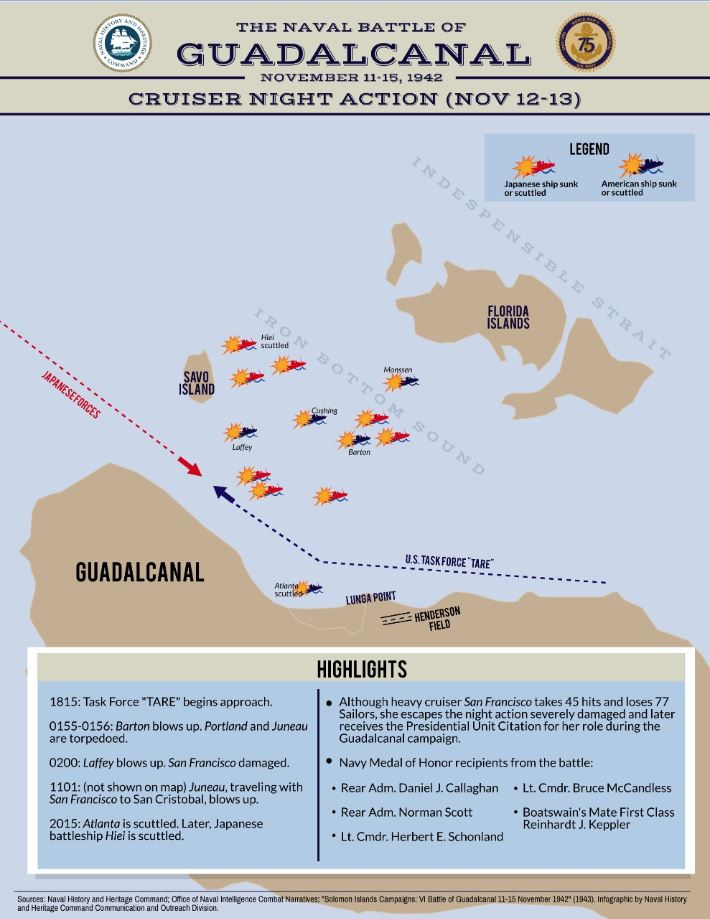

A month later, during the first Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Helena helped defend a troop transport convoy off San Cristobal before engaging in the deadly close-range night naval battle with Japanese forces. According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, on November 12-13:

“American forces paid a heavy price for what most historians agree was a U.S. strategic victory, suffering, either in the battle or subsequent to it, the loss of two light cruisers and four destroyers, as well as damage of varying levels to one heavy cruiser, two light cruisers, and two destroyers. The Japanese too emerged from the battle having suffered notable losses with mortal damage to a battleship along with the loss of two destroyers, with an additional five damaged. Ultimately, the valiant defense turned back the enemy and prevented the heavy attack on Henderson Field.”

It was during this naval battle the five Sullivan brothers died when their ship, Atlanta-class cruiser USS Juneau (CL-52), was sunk. The death of the Sullivan brothers became a major rallying cry for Americans during the early days of the war, according to the Navy History and Heritage Command. Allen’s team discovered Juneau’s wreckage on St. Patrick’s Day. Allen has also discovered the wrecks of cruiser USS Indianapolis and carrier USS Lexington.

On July 6, when Helena was hit by three torpedoes, the ship’s bow was severed, remaining afloat, as the rest of the superstructure, cut in half, jackknifed and quickly sank, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Of the 900 crewmembers onboard when Helena sunk, 732 survived the sinking and were ultimately rescued. Nearly half the survivors were rescued the first night, with about 275 reaching a nearby island in small whaleboats towing life rafts, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS Helena in 1943. US Navy PhotoAbout 200 crewmembers were at first clinging to the bow of the ship which didn’t initially sink. A Navy search and rescue plane dropped life rafts for the crew to use. After spending a day trying to reach a nearby island, the wind and current pushed the flotilla of life rafts further out to sea. After a second day and night in the water, the remaining 165 sailors reached another island, Vella Lavella, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS Helena in 1943. US Navy PhotoAbout 200 crewmembers were at first clinging to the bow of the ship which didn’t initially sink. A Navy search and rescue plane dropped life rafts for the crew to use. After spending a day trying to reach a nearby island, the wind and current pushed the flotilla of life rafts further out to sea. After a second day and night in the water, the remaining 165 sailors reached another island, Vella Lavella, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

“Two coastwatchers and loyal natives cared for the survivors as best they could, and radioed news of them to Guadalcanal. The 165 sailors then took to the jungle to evade Japanese patrols.”

Ten days later, the remaining crew was rescued on July 16.