Hurricane Maria’s trail of destruction in Puerto Rico and the arrival of a new administration may provide the impetus to overhaul a century-old federal law restricting the movement of cargo between U.S. ports to vessels that are American-built, crewed, and owned and operated vessels, a panel of maritime experts said Friday.

Speaking at the Heritage Foundation, James Coleman, a law professor at Southern Methodist University, used the restarting of the Puerto Rican power grid as an example of the law’s restrictiveness in the wake of Maria.

Months after the hurricane, about 25 percent of the island’s residents remain without power in a system that is dependent upon oil to run its generators. Producers “notified the power utility they would be cutting back the fuel supply … until they could afford the fuel” coming from the mainland.

That translates into brownouts in areas where power had been restored and likely even more delays in restarting where service has been lost, he said.

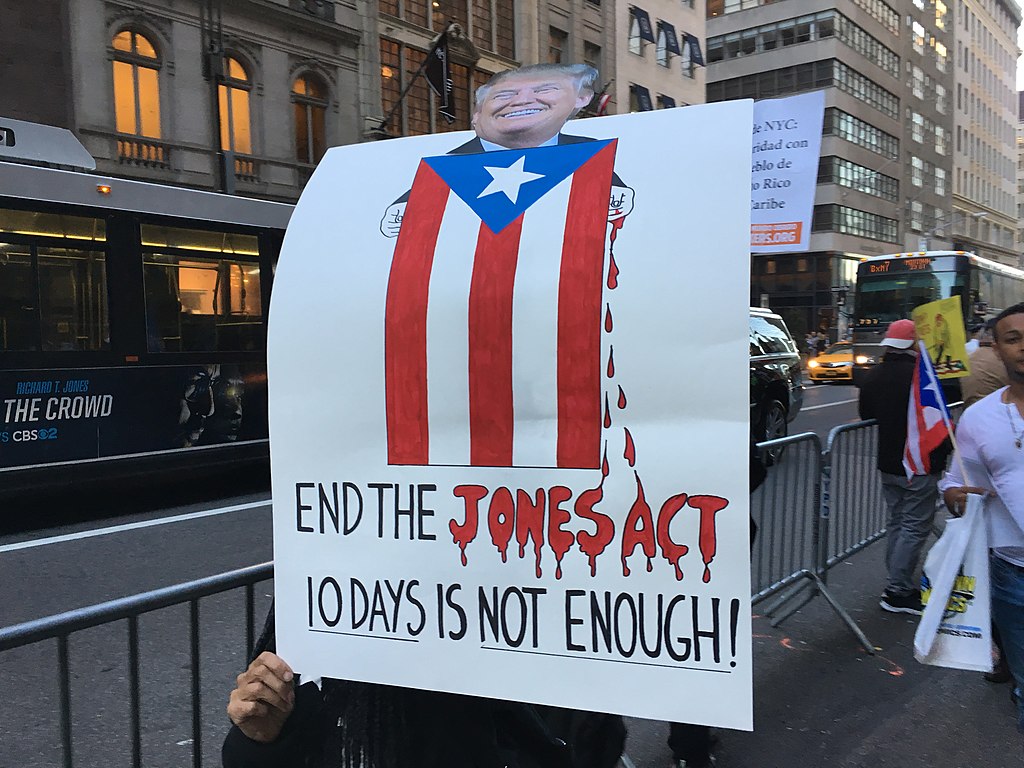

In the immediate aftermath of Maria, President Donald Trump waived provisions of the Jones Act to provide shelter, fuel, food, water, and medicine to the island, an act that disturbed congressional supporters of the law, such as Rep. Duncan Hunter, (R-Calif.), chairman of a committee that has oversight of the Coast Guard and maritime affairs.

Coleman said in his opening remarks at the forum co-sponsored by the Federalist Society, “It is cheaper for U.S. producers to ship their oil and [natural] gas to Europe than it is to ship to U.S. consumers.”

Rob Quartel, a former member of the Federal Maritime Commission, said, “We didn’t have a global world like we have today” in calling for the repeal or reform of the Jones Act. He said it has outlived one of its major announced intents of providing a fleet of deep-draft merchant ships to the country in times of war, trained seamen and officers and steady business for American shipyards in peacetime.

As for the number of shipyards, seamen, size of the American deep-draft, ocean-going fleet under the Jones Act or otherwise, “the numbers just keep getting worse and worse,” he said.

“American business can buy foreign aircraft” and trains and still operate inside the United States, Quatrel said.

Noting that Hillary Clinton, as had most other presidential candidates, supported the law, Coleman said, “[Donald Trump] didn’t take a position on the Jones Act.” Because of that, “there is an opening for reform … an opening for repeal.” He said the argument inside the administration of what position to take could come down to adopt an “America First approach” or an “Energy Dominance approach” regarding the act.

Quartel said the issue of continuing the Jones Act as it is not a Democratic or Republican issue. It cuts across party lines and depends upon what industry or union is in a member’s district or important in a senator’s state. “Industry spends massive, massive, massive amounts of money” to keep the status quo.

The energy market is an example of the volatility of global trading, the changing trade routes to supply immediate demand and using foreign vessels for exploration and production. Jonathan Waldron, a partner at Blank Rome law firm, said the American offshore energy industry is heavily dependent on foreign-built and -operated vessels for drilling and pipe-laying, as well as transporting product. He added it is also subjected to at times inconsistent enforcement practices as to what is acceptable and what is not by Customs and Border Protection agents “in how you operate off-shore.”

As for waivers to the Jones Act provisions as happened with the disaster response to Hurricane Maria, he noted that the traditional path can be fast-tracked when the secretary of defense terms it of national security importance and applies directly to the secretary of homeland security, as happened in Puerto Rico. There was no formal notice sent to Homeland Security that “we use all U.S. capability first” had been met.

The direct waiver approach has been used in the past before the creation of the homeland security department to include bringing in oil skimmers from the Soviet Union to contain and clean-up the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 and several times to restock the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Quartel and Waldron said there would be no increased terror threat by allowing foreign-crewed vessels into inland waterways. Members are already vetted by the State Department and the vessels are known and inspected by the Coast Guard, FBI and other federal and state agencies since they are in international trade with the United States.

“Ninety-nine percent of cargoes from overseas come in foreign-flagged ships,” Quartel said. Crew already undergo an increased vetting process before they are allowed into the United States, Waldron said.

Quartel said the national security argument by supporters of the law resonates, but does not stand up to scrutiny. Using the first Gulf War as an example, he said only one Jones Act ship vessel participated of the more than 480 vessels used to support the coalition. Of those ships, most were foreign-flagged. He added only 85 were American-flagged deep draft ships.