This post will be updated throughout the day with additional information from the investigations.

The fatal collisions of the two guided-missile destroyers USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald between merchant ships that killed 17 sailors were rooted in fundamental failures in the crew’s ability to operate their ships effectively, according to a summary of two investigations the Navy released to the public on Wednesday.

“Both of these accidents were preventable and the respective investigations found multiple failures by watchstanders that contributed to the incidents, said Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson in a statement.

“We must do better.”

In the case of the June 17 collision between Fitzgerald and merchant ship ACX Crystal off the coast of Japan, investigators found that the crew did not understand fundamental rules of maritime transit and did not understand their radars sufficiently. While in transit, the watch lost awareness of the position of the merchant ship, didn’t rouse the commander for assistance when it was clear the ship was in danger.

“The crew was unprepared for the situation in which they found themselves through a lack of preparation, ineffective command and control, and deficiencies in training and preparations for navigation,” read the findings of the summary.

For the Aug. 21 collision of the McCain in the busy waterway in the Strait of Malacca near Singapore, investigators found a less experienced watch team populated by sailors from the damaged cruiser USS Antietam (CG-54) was on duty when the ship entered the waterway. A misunderstanding of how the steering controls on the ship were configured led to a loss of control of the ship two minutes before the collision with the merchant tanker Alnic MC. The impact of the tanker ripped a hole in the hull flooding three berthing areas and drowning ten sailors who were unable to escape from the spaces.

Both crews did not attempt to contact the merchant ship bearing down on them, sound a warning horn, sound a collision warning or sound general quarters before the impacts.

Early results from both investigations have resulted in the removal of the commanders and executive officers of both ships, Capt. Jeffery Bennett, commodore of the Japan-based Destroyer Squadron 15 to which both ships belonged, the Japan-based task force commander Rear Adm. Charles Williams and the commander of U.S. 7th Fleet Vice Adm. Joseph Aucoin.

While not directly related to the findings of the investigations, U.S. Surface Forces commander Vice Adm. Tom Rowden has requested early retirement and U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Scott Swift was passed over for consideration to be the next U.S. Pacific Command head.

Additionally, the Navy is set to roll out a comprehensive review into the underlying causes that allowed the lapses to occur overseen by U.S. Fleet Forces commander Adm. Phil Davidson later this week to present recommendations for corrective action for the surface force.

“We are a Navy that learns from mistakes and the Navy is firmly committed to doing everything possible to prevent an accident like this from happening again,” Richardson said.

“We must never allow an accident like this to take the lives of such magnificent young sailors and inflict such painful grief on their families and the nation.”

Aug. 21, 2017: USS John S. McCain Collision

The afternoon before the collision some members of USS John S. McCain attend a navigation brief, preparing the crew for transiting the Singapore Strait and entering Sembawang, Singapore for a scheduled port call the next morning.

The afternoon before the collision some members of USS John S. McCain attend a navigation brief, preparing the crew for transiting the Singapore Strait and entering Sembawang, Singapore for a scheduled port call the next morning.

This routine briefing is generally held before a ship enters known congested waterways or port, and according to the report, “is designed to provide maximum awareness of the risks involved.”

At the time of the collision the next morning, the principal watchstanders, including the Officer of the Deck who was in charge of McCain’s safety and the Conning Officer on watch, did not attend the Aug. 20 navigation brief.

On Aug 21, before dawn, McCain was operating as a darkened ship – all exterior lighting except navigation lights were extinguished, and all interior lighting was switched to red. Also, all door and hatches were closed. Scuttled – circular openings which can be opened independently of hatches – were open to allow easier access between spaces.

At 4:18 a.m. – about an hour before McCain planned to enter the congested Singapore Strait – the navigation evaluator and shipping officer joined the commanding officer and watch crew on the bridge. The executive officer arrived on the bridge at 4:30 a.m., to provide additional supervision.

Typically, the commanding officer and executive officer are on the bridge, providing additional support, as ships enter ports and congested shipping lanes. to provide additional supervision. Also, when transiting such narrow channels as those entering or exiting ports, crew members with specialized navigation and ship handling qualifications, called the Sea and Anchor Detail, are on watch.

But as McCain entered the Singapore Strait Traffic Separation Scheme at 5:20 a.m., the ship’s Sea and Anchor Detail wasn’t scheduled to be on the bridge until 6 a.m. A U.S. warship’s Sea and Anchor detail are among a ship’s most experienced ship handlers. Ports around the globe establish these heavily orchestrated traffic separation schemes in an attempt to help marine traffic maintain safe distances from each other.

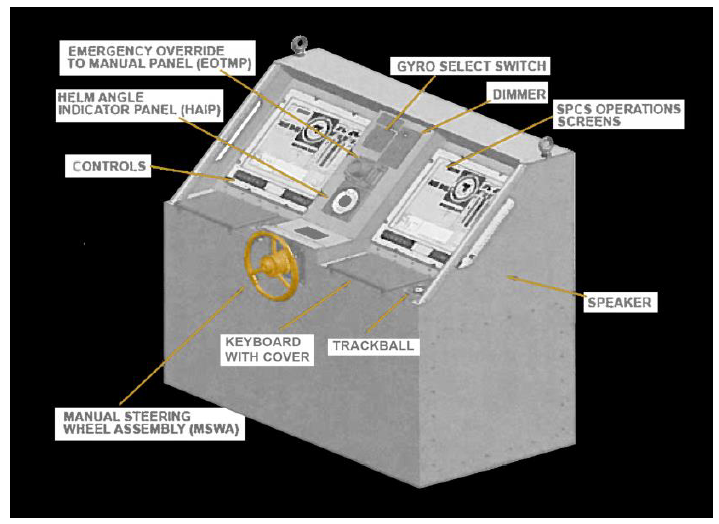

McCain entered the Singapore Strait Traffic Separation Scheme with a bridge manned by a less experienced watch team, including steering controlled by sailors temporarily assigned from USS Antietam (CG-54) which ran aground in January. The two ships use different types of steering control systems.

“Multiple bridge watchstanders lacked basic level of knowledge on the steering control system, in particular the transfer of steering and thrust control between stations,” the report states.

This lack of training becomes a crucial factor contributing to the collision.

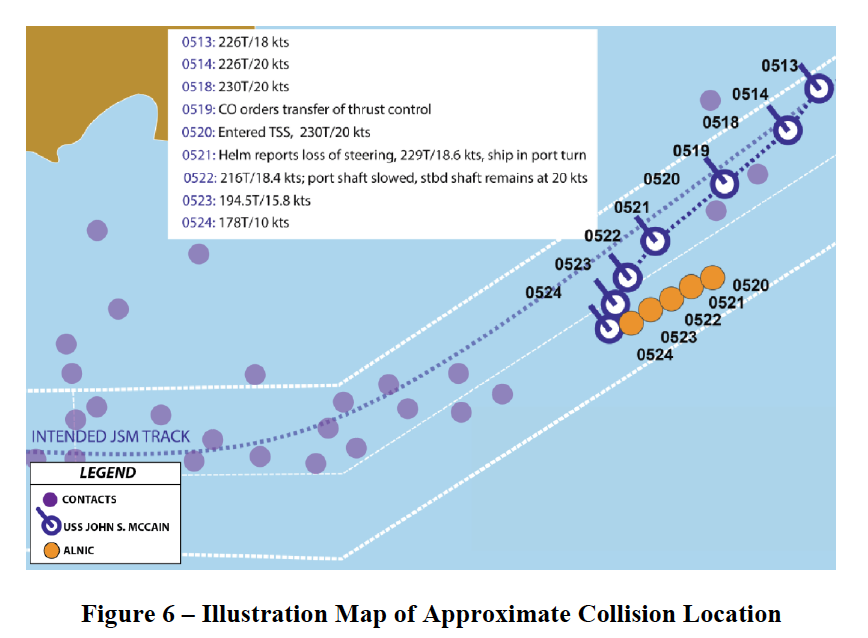

Just as McCain entered the heavily congested Singapore Strait, the commanding officer noticed the helmsman – the watchstander temporarily assigned from Antietam who was steering the ship – was having difficulty maintaining course while also adjusting the throttles for speed control on an unfamiliar steering control system.

In an attempt to help the struggling helmsman, the commanding officer had the watch team divide the steering and throttle controls between two steering stations. Steering would remain under control of the original helmsman, but speed control would be taken over by a second watchstander brought to a control panel next to the helmsman.

Both the helmsman and second watch stander asked to handle speed controls were inexperienced with McCain’s control system. Unknown to both all controls – steering and speed – were mistakenly transferred to the second station. This switch also caused the rudder position to change, from 1-4 degrees right rudder to amidship.

The helmsman, thought steering control was lost, when in reality, it had simply been shifted to a different control station.

The helmsman, thought steering control was lost, when in reality, it had simply been shifted to a different control station.

With a perceived loss in steering, the commanding officer – who also didn’t realize all controls had shifted stations – ordered the ship to slow its speed to 10 knots from 20 knots, and eventually slow to 5 knots.

But the second watchstander asked to control speed, only reduced the speed of McCain’s port shaft. The throttles were not coupled together, meaning the starboard shaft continued at 20 knots.

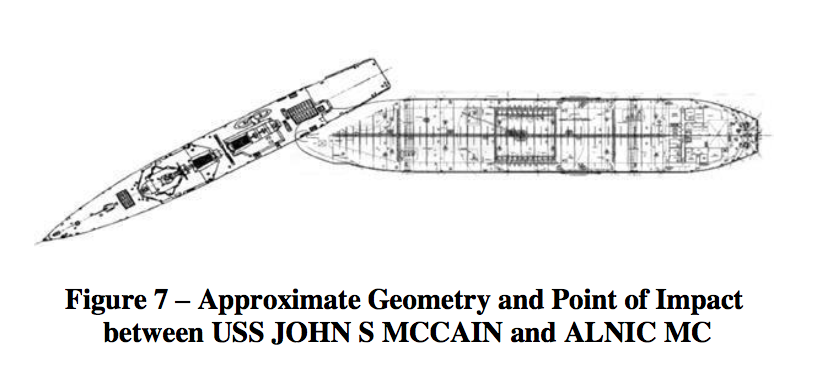

“The combination of the wrong rudder direction, and the two shafts working opposite to one another in this fashion caused an un-commanded turn to the left (port) into the heavily congested traffic area in close proximity to three ships, including the Alnic.”

For about three minutes, McCain sailed on a course to collide with Alnic, without anyone able to steer the ship, and without the commanding officer or anyone else on the bridge fully understanding the forces acting on the ship or Alnic’s course and speed relative to McCain’s.

“The commanding officer and others on the ship’s bridge lost situational awareness,” the report states. “Personnel assigned to ensure these watchstanders were trained had an insufficient level of knowledge to effectively maintain appropriate rigor in the qualification program. The senior most officer responsible for these training standards lacked a general understanding of the procedure for transferring steering control between consoles.”

When the watchstanders regained control of steering – shifted to a third control station – and corrected the mismatch between port and starboard shafts, McCain’s crew was left with no time to correct course.

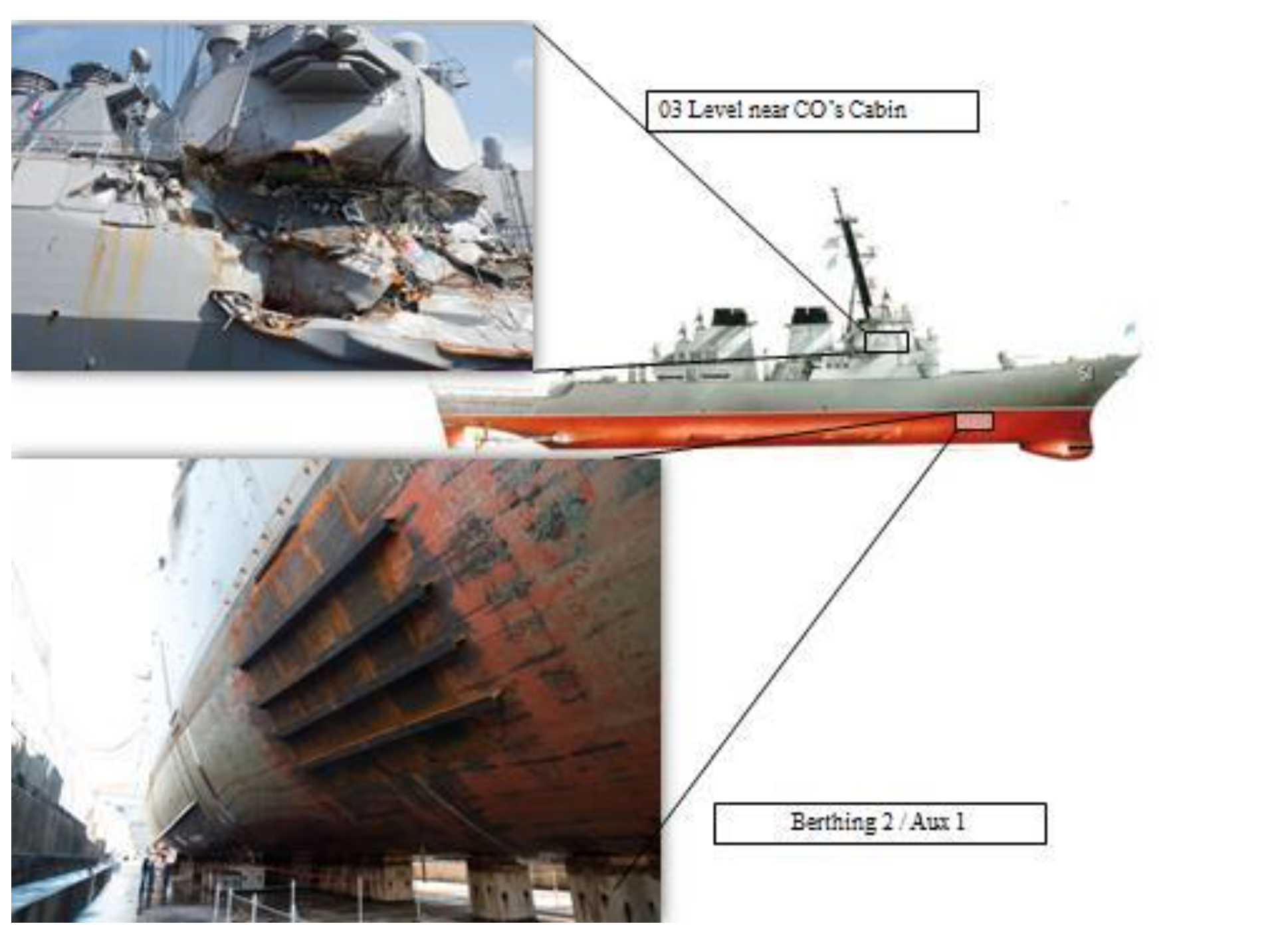

A minute later, at 5:24 a.m., McCain crossed in front of Alnic’s bow and was hit in berthing compartments three and five. The collision created a 28-foot diameter hole both below and above McCain’s waterline.

All 10 sailors killed in the collision were below the waterline, in berthing compartment five. The space, normally 15 feet wide, was compacted by the collision to 5 feet wide, and flooded in less than a minute, according to Navy investigators. Two sailors in the compartment were able to escape.

The collision was felt throughout the ship, knocking some watchstanders from their feet, causing some sailors to report thinking the ship ran aground or had been attacked. Sailors closest to the point of impact described the jolt and sound as being like an explosion.

McCain’s executive officer ordered the collision alarm sounded after the collision. The commanding officer remained on the bridge while the executive officer left to assist with damage control efforts.

McCain’s executive officer ordered the collision alarm sounded after the collision. The commanding officer remained on the bridge while the executive officer left to assist with damage control efforts.

Alnic and McCain remained attached to each other for a couple of minutes after the collision. After separating, McCain developed a 4-degree list to port as the ship flooded.

At 5:30 a.m. McCain requested tugboats and pilots from Singapore Harbor to assist getting the ship to Changi Naval Base. McCain also changed its mast lighting to one red light over a second red light – indicating the ship is not under command. Under the International Rules of the Nautical Road, this lighting configuration warns other ships due to exceptional circumstance, the vessel was unable to maneuver as required.

The space containing some of McCain’s internal communications controls, located next to berthing compartment five, flooded, likely causing the ship to lose much of its internal communications. The crew used handheld radios and sound powered phones to communicate.

The space containing some of McCain’s internal communications controls, located next to berthing compartment five, flooded, likely causing the ship to lose much of its internal communications. The crew used handheld radios and sound powered phones to communicate.

Most sailors in berthing compartment three were able to evacuate, but two were trapped and needed to be cut out of debris as water entered the space. At least one scuttle was shut and fire main valves were closed to limit flooding.

By 6:30 a.m., McCain was able to proceed under its own power at an average speed of three knots to Changai Naval Base, Singapore. McCain’s electronic navigational aids were operational, but with multiple warning and alerts illuminated, reducing the navigation team’s confidence in the systems’ reliability. The team relied on “seamen’s eye” to stay on track.

Also, many sailors moved to the flight deck to avoid the stifling temperatures below deck and air fouled by fuel spills and a lack of ventilation across the ship.

At about noon on Aug. 21, nearly seven hours after the collision, McCain entered the harbor in Singapore. Five sailors were treated at Singapore General Hospital with severe injuries, out of a total of 48 injured sailors. Of the 43 other sailors injured, they continued assisting with damage control and recovery efforts immediately following the collision.

Navy divers would need seven more days to recover the 10 of the sailors killed in the collision.

June 17, 2017: USS Fitzgerald Collision

USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) departed homeport Yokosuka, Japan, and spent much of the day performing routine training and equipment loading operations off the coast of Japan. The weather was reported as pleasant with unlimited visibility and calm seas.

USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) departed homeport Yokosuka, Japan, and spent much of the day performing routine training and equipment loading operations off the coast of Japan. The weather was reported as pleasant with unlimited visibility and calm seas.

At about 11 p.m., after a long day of training, the commanding officer and executive officer left the bridge as Fitzgerald started transiting to sea from the Sagmi Wan operating area. Traveling at 16 knots, Fitzgerald passed Oshima Island and entered an area of increased shipping traffic.

Fitzgerald was operating as a darkened ship – all exterior lighting except navigation lights were extinguished, and all interior lighting was switched to red. Also, all doors and hatches were closed. Scuttles – circular openings which can be opened independently of hatches – were open to allow easier access between spaces. Fitzgerald also had not turned on its Automated Identification System, which uses the Global Positioning System to provide real-time updates of commercial ship positions.

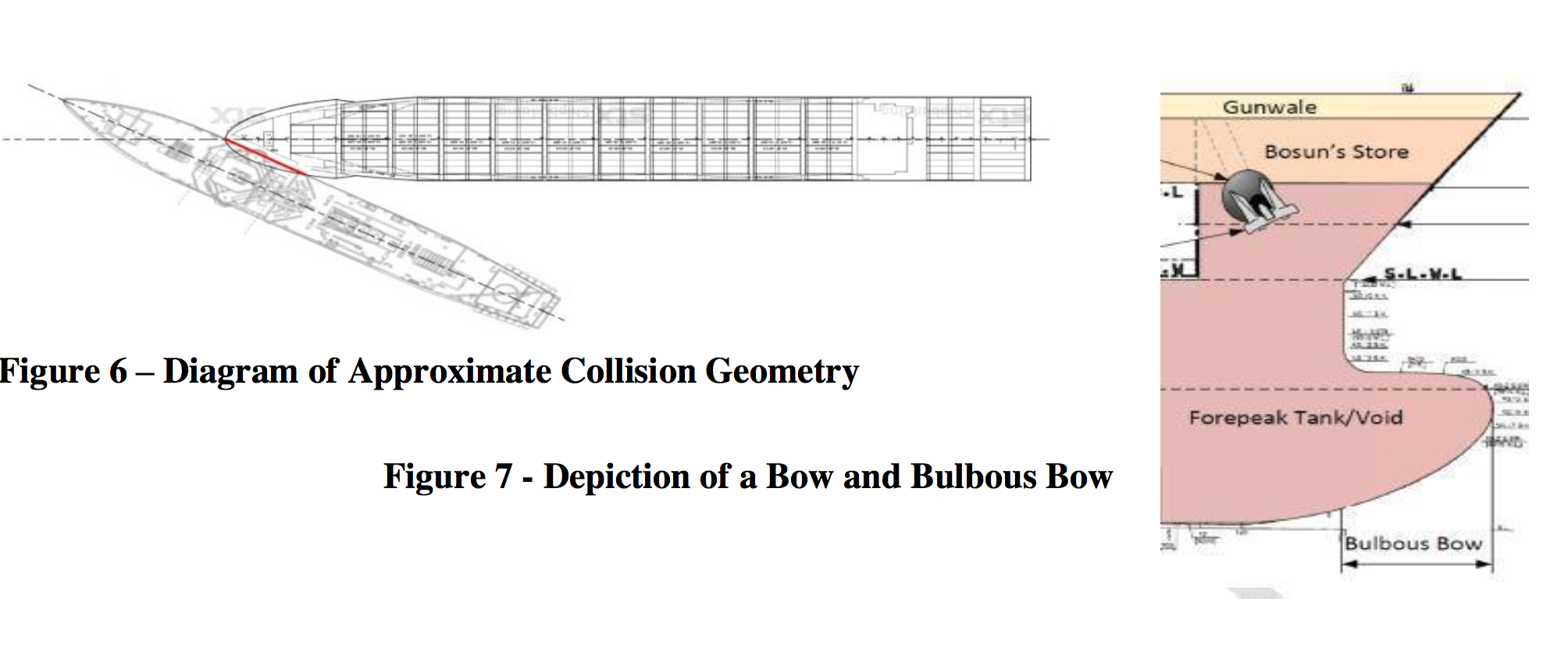

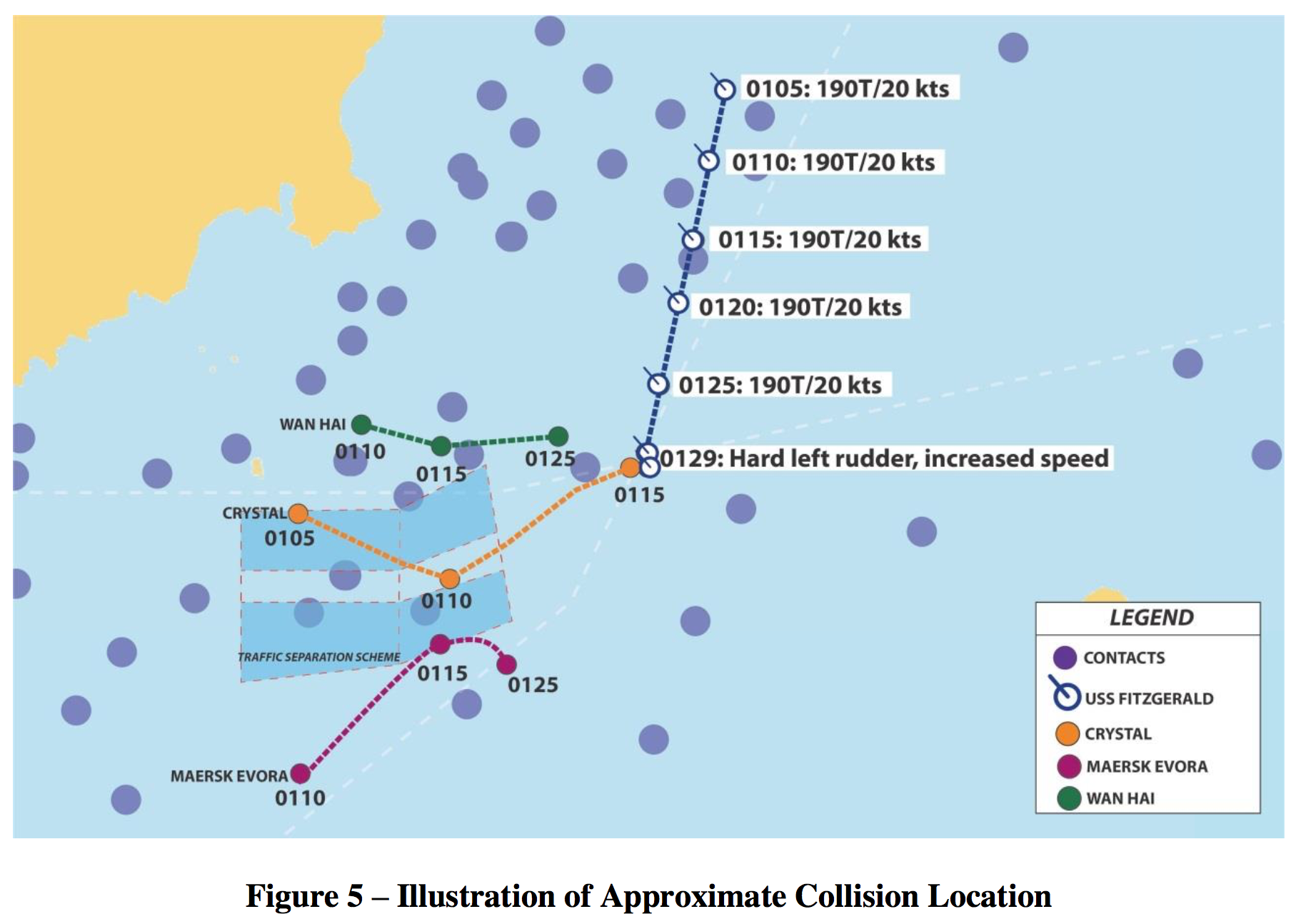

By 1 a.m. on June 17, the report describes Fitzgerald increasing speed to 20 knots and steadily passing other ships in the Mikomoto Shima Vessel Traffic Separation Scheme. Ports around the globe establish these heavily orchestrated traffic separation schemes in an attempt to help marine traffic maintain safe distances from each other.

Fitzgerald’s approved navigation track did not account for, nor follow, the Vessel Traffic Separation Schemes in the area. Watchstanders also did not appear to follow the commanding officer’s standing orders regarding contact with other ships. The report lists 13 instances Fitzgerald came within 3 nautical miles of another ship and the officer of the deck did not alert the commanding officer.

Fitzgerald’s approved navigation track did not account for, nor follow, the Vessel Traffic Separation Schemes in the area. Watchstanders also did not appear to follow the commanding officer’s standing orders regarding contact with other ships. The report lists 13 instances Fitzgerald came within 3 nautical miles of another ship and the officer of the deck did not alert the commanding officer.

In one instance, at 1:08 a.m., Fitzgerald cut across the path of three ships, 2.5 nautical miles, two nautical miles, and about 650 yards away. The officer of the deck did not notify the commanding officer about any of these incidents.

But the report states failing to notify the commanding officer of such passes was hardly unusual. “The command leadership did not foster a culture of critical self-assessment. Following a near-collision in mid-May, leadership made no effort to determine the root causes and take corrective actions in order to improve the ship’s performance.”

At this time, three merchant vessels were approaching Fitzgerald from its starboard side. These vessels, including motor vessel ACX Crystal, were each close enough and on a track to pose a collision risk with Fitzgerald.

Citing the International Rules of the Nautical Road, the report states Fitzgerald was in what’s considered a crossing situation with each of these ships. According to the report, “In this situation, Fitzgerald was obligated to take maneuvering action to remain clear of the other three, and if possible, avoid crossing ahead.”

Citing the International Rules of the Nautical Road, the report states Fitzgerald was in what’s considered a crossing situation with each of these ships. According to the report, “In this situation, Fitzgerald was obligated to take maneuvering action to remain clear of the other three, and if possible, avoid crossing ahead.”

Also in this situation, international navigation rules also obligate the other vessels to take evasive action if it appeared Fitzgerald was maintaining course. Yet for the 30 minutes leading up to the collision, neither Fitzgerald nor Crystal took any such action.

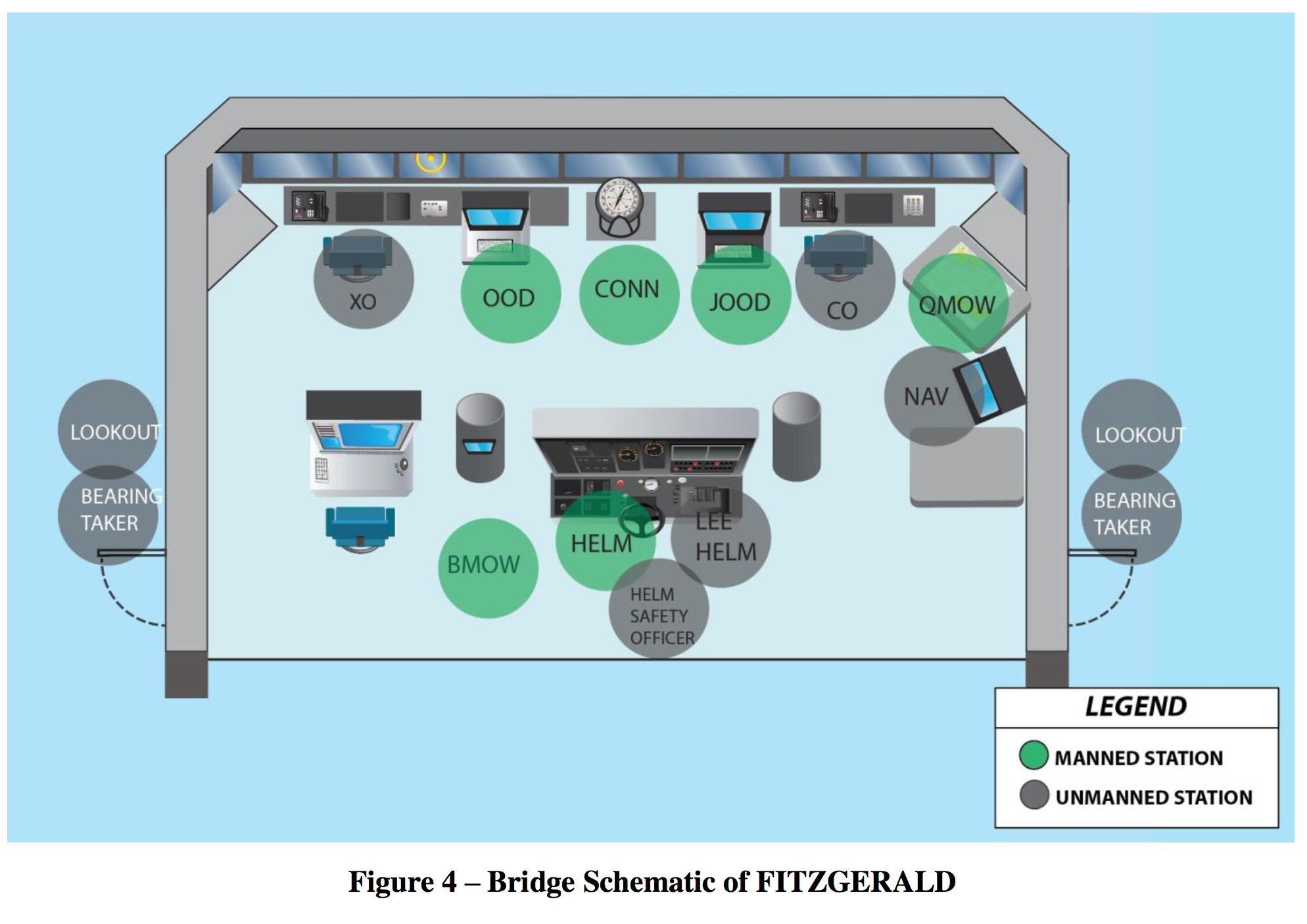

The officer of the deck and the junior officer of the deck discussed the relative positioning of the three other vessels and whether action was needed to avoid them. In what would ultimately prove to be a deadly mistake, the officer of the deck confused Crystal with another vessel which was further away, and initially decided no action was needed.

“Eventually, the officer of the deck realized that Fitzgerald was on a collision course with Crystal, but this recognition was too late,” the report states.

At 1:27 a.m., the officer of the deck ordered a course change, but quickly rescinded the order. Instead, the officer of the deck ordered an increase to full speed and a rapid turn to the port. Crystal was coming from the starboard.

These orders were not carried out.

Ultimately, at 1:29 a.m., the bosun’s mate of the watch, a more senior supervisor on the bridge, took over the helm and executed the orders. But it was too late.

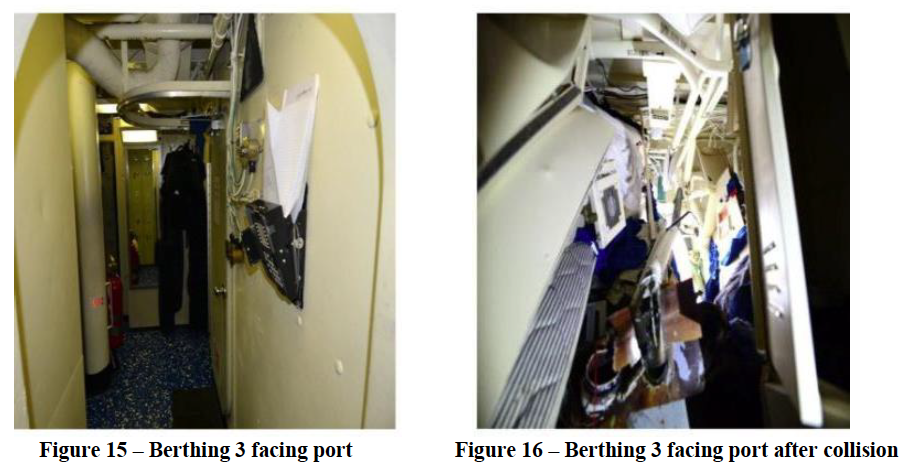

At 1:30 a.m., approximately 56 nautical miles southwest of Yokusuka, near the Izu Peninsula and within sight of land, Crystal slammed into Fitzgerald’s starboard side, hitting both above and below the waterline.

The seas were relatively calm between 2-feet and 4-feet. The sky was dark, the moon was relatively bright, there was scattered cloud cover and unrestricted visibility. Neither ship attempted to contact the other and Fitzgerald did not sound the collision alarm.

Seven sailors were killed in the collision.

The officer of the deck never called the commanding officer, as prescribed by Navy procedures, to alert him to the situation and allow for more senior oversight and judgment.

The report clearly faults the officer of the deck, “the person responsible for safe navigation of the ship, exhibited poor seamanship by failing to maneuver as required, failing to sound the danger signal and failing to attempt to contact Crystal on Bridge to Bridge radio.”

But the report also faults the remainder of the watch team as failing to fully grasp the pending danger facing Fitzgerald. Watch team members responsible for radar operations failed to properly tune and adjust radars to maintain an accurate picture of other ships in the area. Supervisors in charge of maintaining the navigation track and position of other ships were unaware of exiting traffic separation schemes and the expected flow of marine traffic.

Teams in the Combat Information Center, where tactical information is fused to provide maximum situational awareness, also failed to provide the officer of the deck with relevant input and information.

Watchstanders performing physical look-out duties were only on Fitzgerald’s port side. In other words, with Crystal and the other two ships off the starboard side of Fitzgerald, the sailors on look-out never knew Crystal was coming.

Following the collision, the Fitzgerald crew fought to prevent the severely damaged ship from sinking. The commanding officer was among the crew members injured, and was transported to Japan for treatment. Ultimately, the commanding officer, executive officer, and command master chief were relieved of their command.

In October, the Navy honored 36 Fitzgerald sailors for the damage control and rescue efforts following the collision.