This post has been updated with an additional statement from U.S. 7th fleet.

THE PENTAGON — The top three leaders of the guided-missile destroyer involved in the June collision, which resulted in the death of seven sailors and hundreds of millions of dollars in damage, have been removed from their positions, the vice chief of naval operations told reporters on Thursday afternoon.

USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) commander Cmdr. Bryce Benson, executive officer Cmdr. Sean Babbitt and command master chief CMC Brice Baldwin were removed from their positions by U.S. 7th Fleet commander Vice Adm. Joseph Aucoin this week based on the early results of several investigations into the June 17 collision between the destroyer and the merchant ship ACX Crystal, VCNO Adm. Bill Moran told reporters.

As the investigations continue, Moran said there could further punitive actions taken, including against Fitzgerald’s leadership. Neither Benson, Babbitt nor Baldwin were on the bridge when the collision occurred.

While the leadership have not been separated from the Navy, Moran said being detached for cause because of this incident sends a message.

“Vice Adm. Aucoin’s judgment is that he needs to take action to hold people accountable based on what he does know,” Moran said.

“Imagine the ship and the crew are there and we’re trying to determine what to do with that ship and that crew: if it’s clear to him that some members of that crew should no longer be doing this line of work, it’s time to move them on, it’s time to take accountability actions.”

In a early Friday statement, U.S. 7th Fleet said it had disciplined several other sailors who were on duty during the collision

“Several junior officers were relieved of their duties due to poor seamanship and flawed teamwork as bridge and combat information center watchstanders. Additional administrative actions were taken against members of both watch teams,” read the statement.

“The collision was avoidable and both ships demonstrated poor seamanship. Within Fitzgerald, flawed watch stander teamwork and inadequate leadership contributed to the collision that claimed the lives of seven Fitzgerald sailors, injured three more and damaged both ships.”

The removals and additional punishments for those standing watch during the incident come as the Navy released a supplemental investigation that detailed the circumstances aboard Fitzgerald that resulted in the death of the seven sailors who drowned in their berthing space. The line of duty investigation occurs when a service member dies to make sure they did not die due to their own misconduct.

While the service was clear that the supplemental investigation was only into the events following the collision and not on the conduct of the crew before they hit the merchant ship, there are signs in the 41-page summary that there were substantial failures by the watch ahead of the damage control efforts.

According to a timeline of events, neither a collision alarm nor general quarters were sounded ahead of Crystal hitting the ship at about 1:30 a.m. on June 17, and the first indication to most of the crew that the ship had hit anything was the lurch they felt in their bunks.

“Some of the sailors who survived the flooding in Berthing 2 described a loud noise at the time of impact,” read the report.

“Other Berthing 2 sailors felt an unusual movement of the ship or were thrown from their racks. Still other Berthing 2 sailors did not realize what had happened and remained in their racks. Some of them remained asleep. Some sailors reported hearing alarms after the collision, while others remember hearing nothing at all.”

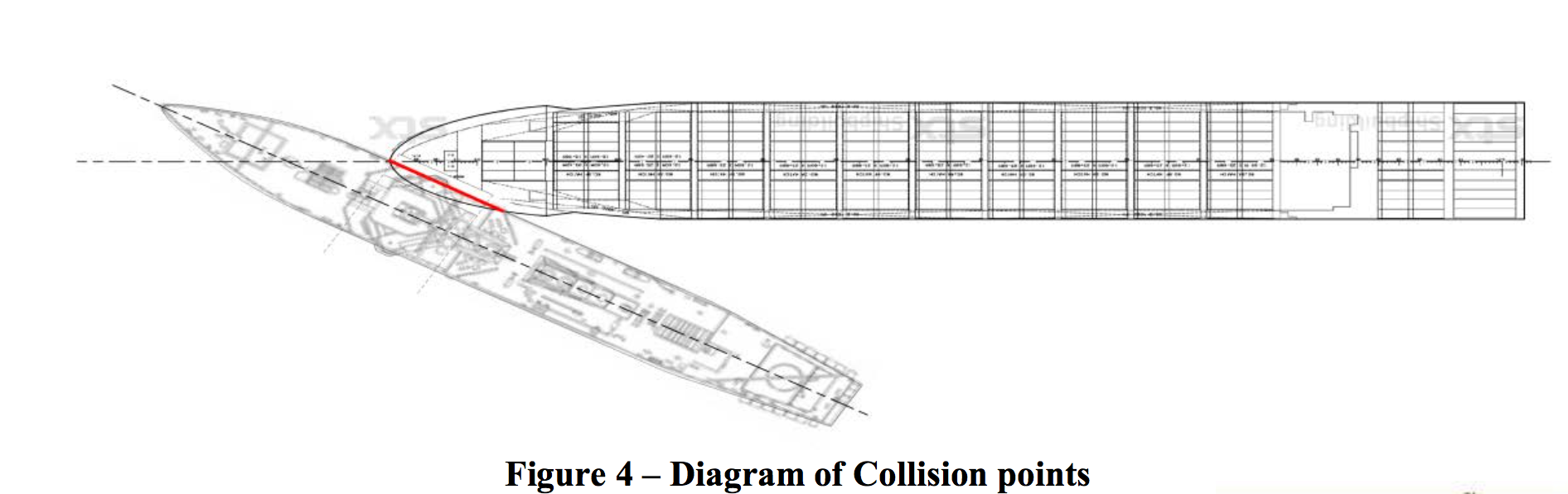

According to the report, 35 sailors in Berthing 2 were in the space when the bulbous bow of Crystal pierced Fitzgerald’s hull in an adjacent access space that was only separated from sailors’ racks by a non-watertight door. The impact punched a 17-foot-by-13-foot hole in the side of the ship below the waterline.

“As a result, nothing separated Berthing 2 from the onrushing sea, allowing a great volume of water to enter Berthing 2 very quickly,” read the report.

In a timeframe described as anywhere from 30 seconds to about a minute, water poured into Berthing Area 2 quickly rising to waist and then head height.

“Debris, including mattresses, furniture, an exercise bicycle, and wall lockers, floated into the aisles between racks in Berthing 2, impeding sailors’ ability to get down from their racks and their ability to exit the space,” read the report.

“The ship’s five to seven-degree list to starboard increased the difficulty for sailors crossing the space from the starboard side to the port side.”

Still, 28 sailors were able to escape from the berthing area in an orderly fashion in the scant seconds the crew had to leave the space as it flooded with water. The seven sailors who died in Berthing 2 were in the racks closest to the access space that was vented to the open ocean “and directly in the path of the onrushing water.”

Moran praised the response of the sailors.

“When we look at that compartment, when we look at the pictures, some of them you’ve seen, it’s somewhat amazing that we didn’t lose far more,” he said on Thursday.

“By the time the last two sailors reached the ladder on the way up to the scuttle and out of that compartment, it had been about 90 seconds and by that time the water was up to their necks.”

In particular, Moran singled out the actions of Gary Leo Rehm Jr., who was advanced to Chief Petty Officer posthumously this week. Rehm helped get several sailors out to the exits while Berthing 2 was flooding and was one of the seven who died.

“In Gary Rehm is the sprit, courage and values of what we’d expect of a chief petty officer,” Moran said.

“CPO Rehm’s actions that night clearly embodied those values as he and several others crew members did some extraordinary things to make sure they could save additional lives. Selflessly he gave his own, and saved the ship, which was in jeopardy after the collision.”

Meanwhile, the superstructure of Fitzgerald was caved in, crushing and warping Benson’s stateroom and leaving him hanging to the side of the hull in the open air for 15 minutes.

“Five sailors used a sledgehammer, kettlebell and their bodies to break through the door into the CO’s cabin, remove the hinges, and then pry the door open enough to squeeze through. Even after the door was open, there was a large amount of debris and furniture against the door, preventing anyone from entering or exiting easily,” read the report.

“A junior officer and two chief petty officers removed debris from in front of the door and crawled into the cabin. The skin of the ship and outer bulkhead were gone and the night sky could be seen through the hanging wires and ripped steel. The rescue team tied themselves together with a belt in order to create a makeshift harness as they retrieved the CO, who was hanging from the side of the ship.”

Benson was one of three sailors who were evacuated from the ship, as his condition continued to worsen after his rescue.

Damage control parties fought the flooding for an hour before they could signal for help, since the collision had knocked out the ship’s long-range communications. The crew eventually sent out a distress call via a personal cell phone.

In the midst of clearing the hundreds of tons sea water from the ship, the crew also rescued three sailors who were trapped in the sonar room below the waterline. In the subsequent hours, the crew was able to get the destroyer moving again under its own power while the Japan Coast Guard evacuated the injured sailors, including Benson.

The ship eventually returned to Yokosuka and continued repairs to stabilize the ship and recover the sailors left behind in Berthing 2.

The report released on Thursday will be far from the last to emerge from the investigation.

“The families had been asking since the initial line of duty investigation for additional information that would describe how their sons died,” Moran said.

“They’re in a better place, I hope, for having the knowledge of how it occurred.”

The Navy also completed a safety investigation and continues to conduct a Navy’s Manual of the Judge Advocate General (JAGMAN). Moran indicated that the complete reports would not be released to the public but that Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson was committed to share as many details as possible of what went wrong on June 17.

While the investigations continue, the Navy announced it would transport Fitzgerald back to the U.S. for further assessment and repairs. While the assessments are ongoing, several naval analysts have told USNI News the costs could easily rise above $500 million.