James Schlesinger was at once a lifelong Washington creature and a man who rose above politics, achieving the heights of power in both Republican and Democratic administrations.

From 1973 to 1975, Schlesinger guided the Pentagon establishment from its wars in Southeast Asia to an aggressive posture of toe-to-toe superpower confrontation. As Washington imploded around him, he viewed the soldier, sailor, airman and Marine as throwbacks to the days in which America was the stalwart force for good and defender of right—what he termed the “pillar of stability” in a chaotic world.

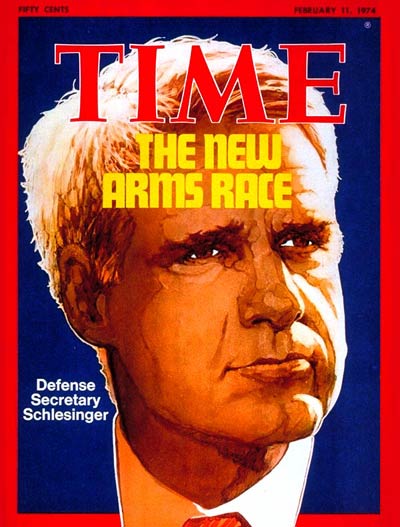

Following brief service as director of Central Intelligence, James Schlesinger took office as the secretary of Defense in July 1973, at the age of only 44, young enough to be the son of some of the men whom he would lead.

He stepped into a maelstrom.

The Defense Department, enervated by ten years of grinding, bloody jungle warfare and just beginning to recover from the body-count era of Robert McNamara, was leery of reformist civilians. Nixon had just announced the end of America’s war in Vietnam, halting conscription and ushering in today’s all-volunteer force. Admirals and generals now had to convince young men to join and stay, while confronting racial unrest and drug dealing on military bases, reaping in the States the whirlwind of mutiny carried over from the disaster in Vietnam.

The military establishment responded to discipline problems by easing the rules, allowing young men in the military to grow their hair longer and even sport beards, further horrifying a World War II generation already disgusted with rebellious youth.

That same generation gaped in horror that summer at the unfolding constitutional—perhaps, some thought, existential—crisis unfolding across the river from the Pentagon.

The Watergate scandal detonated in the very month Schlesinger took office, with revelations under oath that President Richard Nixon had a secret taping system in the Oval Office, rendering him instantly powerless.

The nation’s sons and daughters—the same age as young men just back from Vietnam—carried signs on the National Mall demanding Nixon’s impeachment. The summer testimony was followed by the “Saturday Night Massacre” that fall, then by Nixon’s resignation the following summer.

Government and the nation teetered on the edge of the abyss; middle America lost all faith in its leaders; author David Halberstam’s “best and brightest” departed government for more welcoming sinecures in academia and the private sector.

Such was not an environment in which to rebuild a strong military.

Schlesinger, moving carefully, set the Defense Department on the course it still travels 40 years later, facing the three Ds of modern political science and national security policy: defense, deterrence and détente.

In the fragile domestic ecosystem of the mid-1970s he had to tread lightly, neither alarming a restive American public about looming global war nor allowing the Soviets to sense an opening between American defense and foreign policy.

The Yom Kippur War in the Mideast blew open the fragility of the American-Soviet détente, the OPEC oil embargo further weakened a struggling American economy, and the fall of South Vietnam and the Mayaguez incident contributed to a sense of a world in disarray.

As Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger worked publicly on the Soviet Union’s Leonid Brezhnev, Schlesinger moved to strengthen America’s nuclear deterrent.

He was the Cold Warrior, a staunch advocate for counterforce and countervalue policies in nuclear planning, forceful bulwark for NATO expansion against what he saw as a very dangerous Soviet threat in Eastern Europe, and fundraiser-in-chief for higher defense budgets. Schlesinger did believe in détente, but thought that “we should pursue détente without illusion.” His desire to stand eye to eye with the Soviets was prelude to the Mutual Assured Destruction and countervailing standoffs of the Ronald Reagan/Casper Weinberger era of the nuclear triad. He disagreed with Kissinger about the efficacy of the first set of SALT talks, believing that rather than ratcheting down tension, such negotiations left the United States open to the vulpine Soviet Union.

Schlesinger realized that preparation for superpower confrontation, and concomitant nuclear worries, required a change not in machinery but in thinking. In a nation in no mood for war, he could not simply advocate for more ships and aircraft and infantrymen; instead, he focused on a lighter and more intellectually agile conventional force, to rise in concert with expanding nuclear assets. He was bothered by the sense that the war in Vietnam, rather than ushering in a new era of military thought and strategy, was instead driven by poor thinking and worse planning, with generals simply imposing the conventional war they wanted onto the insurgency they faced.

He had no illusions about the real need for conventional forces, and indeed was a powerful voice for funding for these forces on the Hill. But he knew the DOD needed more analysis—not of the Whiz Kid spreadsheet variety, but dispassionate and critical.

Soon after taking office he established the Office of Net Assessment, headed (as now) by Dr. Andrew Marshall, which set in place today’s self-reflective leadership. He approved the Air Force’s A-10 attack plane and F-16 lightweight fighter, both moderately priced aircraft suitable for deployment across the high plains of Germany, both still in service today, both reflective of a different Air Force than one whose generals had bombed the Ruhr.

In his farewell address, published on the Marine Corps’ 200th birthday of 10 November 1975, he spoke of diffusion of power around the world, combined with incoherent American foreign policy and collapse of public support for the armed services.

He pointed up the great challenge of his time, asserting that “only the United States can serve as a counterweight to the power of the Soviet Union.” It was this dichotomy—drawing down from war in the tiniest of nations, while preparing for war in the largest of them—that defined the time, and described the man.

James Schlesinger fought against President Gerald Ford’s proposal to grant amnesty to American draft evaders, believing they represented the worst of American youth, and thus the worst of the United States.

Whether fighting to free peasants in rural societies or preparing for nuclear war, he knew, the American in uniform was the opposite of those who had fled: these were the best the nation had. It was his goal to remind the nation of what it once had taken for granted and now rejected. Serving at a unique moment in American history, James Schlesinger knew that there was no road to follow . . . there was only the path he made by moving forward.