Retired Navy Capt. Don Walsh, a deep-sea submarine officer, oceanographer and renowned explorer who was one of the first to dive to the deepest depths of Earth’s oceans, passed away Sunday, USNI News has confirmed. He was 92.

Walsh, a native of Berkeley, Calif., enlisted in the Navy in 1948 and worked as an aircrewman before he attended the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. He became a submarine officer, commanding USS Bashaw (SSKS-241), and later became the Navy’s first deep submersible pilot.

Walsh was a Navy lieutenant on Jan. 23, 1960, and in command of the bathyscaphe Trieste when he and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard dove deep into the Mariana Trench, intent on reaching and measuring its deepest point.

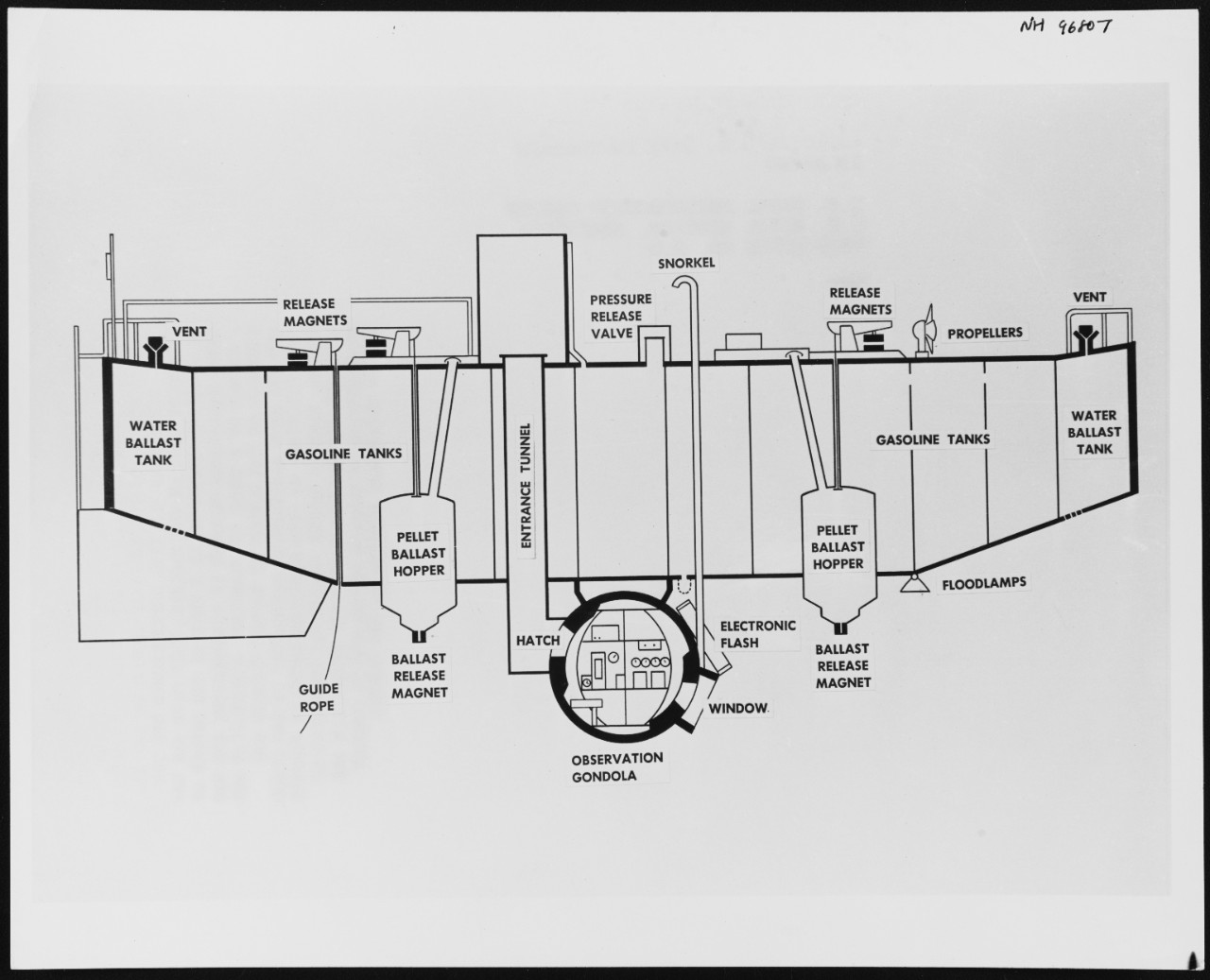

The secret work was codenamed Project Nekton. They rode in a vessel they mostly built in-house.

“Everything on this had to be designed by us and made by us, because there weren’t any commercial vendors, no catalog that sold parts or qualified for 20,000 or 16,000 psi, eight tons per square inch of pressure and to do the things that we wanted to do. Cameras, lights, samplers, sensors, instrument sensors – all of that we had to design and build, or have built,” Walsh said in a 2020 interview with USNI News. “So we were writing the book for deep ocean operations.”

“It was really mare incognita,” or unknown land, he said.

Walsh and Piccard reached the depth of 35,814 feet in an area called Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, located in the Pacific Ocean southwest of Guam – that is a mile deeper than Mount Everest is tall.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented the Legion of Merit to Walsh later that year.

A watch he wore on that deep mission and when meeting Eisenhower at the White House is being auctioned Nov. 15 – bids start at $50,000, per the auction house, according to the Robb Report. Walsh had bought three of the JeanRichard Aquastar 60 watches in San Diego a year before the dive.

Walsh, who spent 24 years in the Navy and earned a doctorate in oceanography, went on to teach at the University of Southern California. Years later, he was in a White House audience when he was recognized for his historic dive by President Bill Clinton, who acknowledged him, along with Titanic discoverer Bob Ballard, at a June 2000 White House ceremony.

In 1997, Walsh began authoring the “Oceans” column in U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings because, as he opined, “naval officers know a lot about sailing on, in, or above the ocean, but they don’t know enough about the ocean itself.” His last “Oceans” column appears in the November 2023 issue of Proceedings. He also served as a consultant on a number of Hollywood movies, including the 1972 disaster movie The Poseidon Adventure.

Walsh, for the past decade, was a frequent guest lecturer on oceanic cruises—particularly ones to locations off the beaten path, such as the Arctic, Greenland, Hudson Bay, and Antarctica.

Last month, he had completed an Arctic cruise on a French icebreaker he wrote to Proceedings editor-in-chief Bill Hamblet.

“We had to run north quite a distance to find any ice to break,” Walsh wrote. “Finally got 10/10 ice about 900 miles south of the North Pole. Our guests really enjoyed the three days we spent working the ice. Using some of our Zodiac boats we put quite a few out on ice floes for a ‘walkabout’.”

Walsh earned many accolades over his long career. This year, he received the Naval Order of the United States’ Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award. In 2012, he received the National Maritime Historical Society’s Distinguished Service Award.

In a 2020 update to NMHS, Walsh wrote that his ongoing work since receiving the award “has taken me on average to eight nations each year. Also, I have made several shipboard expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctica as an expedition staff member. This continues my 50 years of going to the Polar Regions for various activities. Last year, I had the honor of being on a return diving expedition to Challenger Deep, the ocean’s deepest place. I was first to dive there in 1960. This time I did not dive,but was witness to four successful dives there. Then this year, my son (Kelly Walsh) was on board that submersible and dove to the same place on the seafloor that I visited six decades ago.”

The 1960 dive made Walsh something of a plank owner among the community of deep-sea human explorers. His experience brought him credibility and notoriety and enabled his influence within the Navy and halls of Congress as a staunch advocate for continued ocean exploration.

Ocean advocacy

Walsh’s place in history “is assured, as an oceanographer, as a deep-submergence vehicle operator” and when he worked for the secretary of the Navy, as “he periodically would smooth things out with Congress on certain oceanographic-related issues and deep-submergence issues,” Norman Polmar, naval analyst and author, recalled Monday.

“Don was an expert in both exploiting his background to help the Navy oceanography by walking in the front door but also, on a couple of occasions… he did something through the backdoor,” Polmar said, “and he had outstanding abilities in both areas.”

“I learned a lot from him,” he said of Walsh’s “way of explaining complex issues. This is why he was so valuable as a front man and as a back man.”

Polmar recalled in a blog post of meeting Walsh at a Naval Historical Foundation event in 1961. Walsh was “a bright young submariner officer,” he wrote. That evening, he and Walsh struck up a lifelong friendship. “We both hit it off together,” he said. “I just thought very highly of him… I admired and liked him, both professionally and personally.”

“He was a very heartfelt human being,” he added, recounting time spent with Walsh and his wife, Joan, and son, Kelly. One time, he recalled, he had joined Walsh and his young son in a poignant visit to see some old airplanes at Naval Air Station North Island in Coronado, Calif. “It was interesting to see… the close relationship he had with his son,” he said.

“Don just loved aviation and airplanes,” Polmar added. “He was a real aviation buff.”

The 1960 mission

In an April 2014 article in Scientific American, Walsh wrote about the Challenger Deep expedition in recounting his work with Trieste while assigned at the Navy Expeditionary Laboratory in San Diego, Calif.

“This was pretty exciting stuff for a couple of submariners who usually hugged the coast. The last sub that I served on had a maximum operating depth of 300 feet,” he wrote.

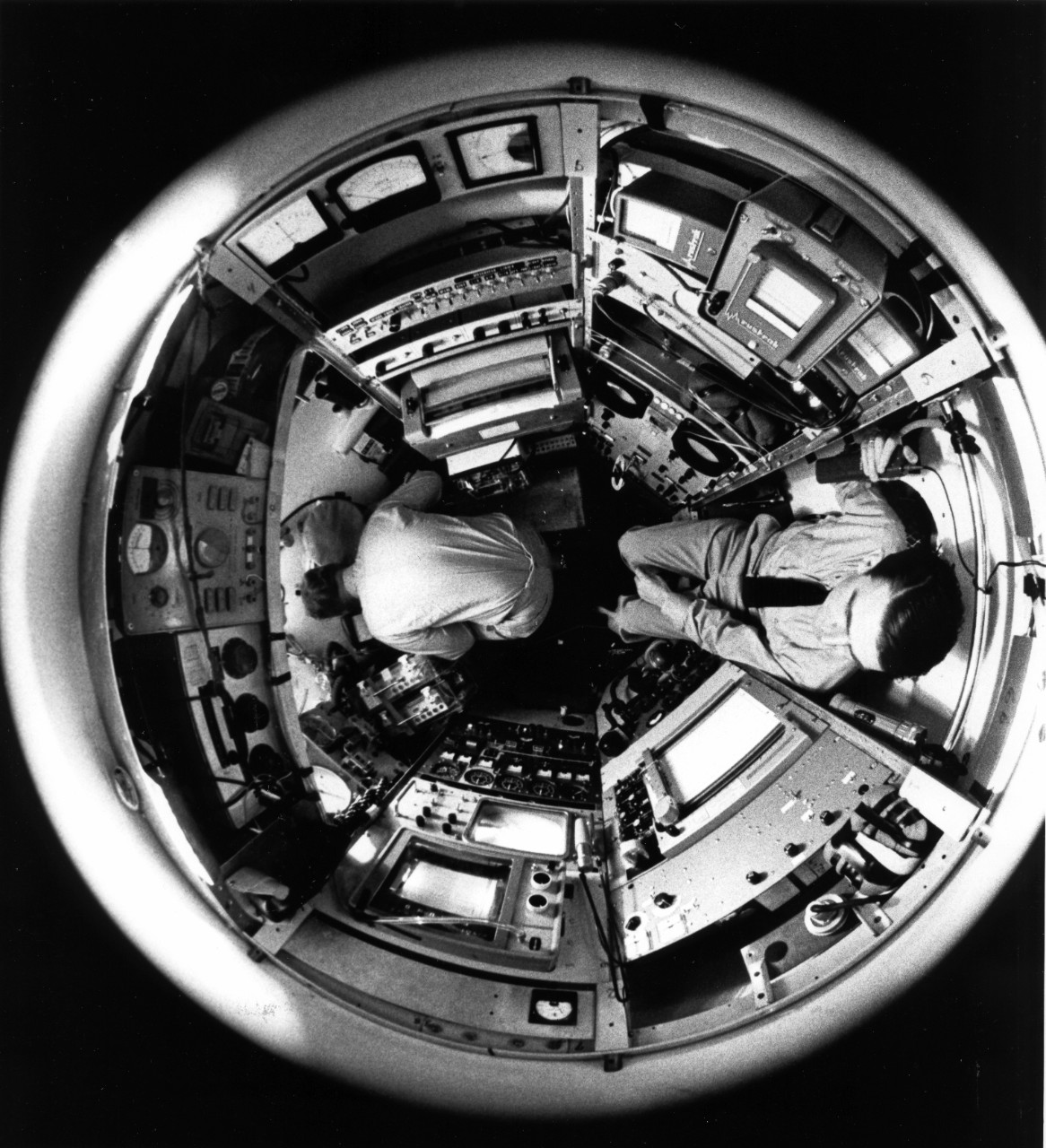

He recounted the work on the bathyscaphe sphere, “a thing of beauty. The walls, five to seven inches thick, were made in three rings and glued together with epoxy at the two joints. The admiral who was head of the Navy’s Bureau of Ships came to see Trieste at NEL. He asked how this very smooth sphere was fastened together. I told him it was glued. He fixed me with an admiral’s ‘evil eye’ and said, ‘Lieutenant Walsh, the Navy does not glue its ships together!’ Perhaps, but ours was glued.”

Later, as work into the deep dive project progressed, Walsh wrote he “found myself in front of Admiral Arleigh Burke, the chief of naval operations. I briefed him and he reluctantly agreed to the project. However he directed that our intentions not be publicized until we were successful. He did not want a high-visibility flop. I called NEL and gave them the good news.”

Multiple test dives were done in 1959, and on Jan. 15, 1960, Walsh and Piccard dove to 23,000 feet in the Nero Deep, in the Mariana Trench, he wrote. They departed Apra Harbor in Guam on Jan. 19, 1960, for Challenger Deep, and Trieste went into the sea the following morning.

“On Jan. 23, by 08:30 we were on our way, hopefully to a successful culmination of Project Nekton,” Walsh wrote. Later, reaching depths “between 4,000 and 7,000 feet a couple of hull penetrators began to weep some water drops. This had happened before and the remedy was simple.”

“At 31,000 feet Trieste was jolted by a muted bang,” he added. “In the past we had some very small external components fail but those events produced sharper sounds of implosions. This noise was much lower in pitch, as if something big had broken. We checked our instrument readings and all seemed well, and Trieste was descending at the same rate as before, so we decided to proceed.”

“Then we passed 36,000 feet,” he wrote. “Where was the bottom? We kept moving down as slowly as possible. Finally, I began to see a bottom trace on the paper chart. I advised Jacques and called off our height above the bottom as we approached it. As we got closer he could see the loom of our lights and released just enough shot to make an easy landing. Our depth gage (sic) read 37,800 feet. We had found a new depth in the Challenger Deep!

“Just before we landed Jacques asked me to look out of the viewport. He said, ‘Do you see that fish on the bottom?” I saw a ‘flatfish’ like a small sole or halibut. It was whitish in color and about a foot long.

“Though very brief, this was an important observation. First, it told us that there was a higher-order marine vertebrate living at this incredible depth. Second, if there was one then there were probably many as this was a bottom-dwelling fish. And third, there were sufficient nutrients and oxygen to support life at the deepest seafloor.

“After we landed Jacques and I shook hands and expressed our feelings of relief and joy. Our small Project Nekton team had said we would do it and we did! It was a great day for all of us who had worked so hard for nearly five months at Guam. “

Walsh and Piccard spent 20 minutes on the ocean floor, reaching the surface three and a half hours later. He recalled that in making the rounds in Congress and the Department of the Navy, he found a much happier CNO. “Admiral Arleigh Burke was smiling a lot more than when I had last seen him!” he wrote.

The ensuing years have seen several dives to Challenger Deep by remotely operated vehicles. Unmanned systems will do “the heavy lifting,” Walsh said in the 2020 USNI News video. But the “human fingerprint,” he added, remains in the technology developed since then to advance the continuation of deep-sea exploration.

Record Dives

The 1960 expedition might remain as the deepest dive yet by a human in a manned vehicle.

Hollywood director James Cameron, in his solo dive to Challenger Deep aboard his submersible Deepsea Challenger, reached a depth of 10,908 meters.

That might be just short of the depths that Walsh and Piccard reached in 1960, according to a 2021 deep-sea research paper that studied and revised Challenger Deep’s depths by the various experiments conducted over the years.

In an October 2022 video seminar about the research, Cmdr. Sam Greenaway, a lead author of the paper and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Corps officer, discussed the various measurements, calculations, locations and estimates of depths measured along Challenger Deep over various expeditions. In the seminar, Greenaway discussed the revised measured deepest depth of Challenger Deep to 10,935 meters – that’s about 35,876 feet. “So 10,935 meters is how deep the ocean is, plus or minus three” meters, he said.

Trieste reached a depth of 10,910 meters, Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger submersible reached a slightly shorter depth, at 10,908 meters, according to Greenaway’s estimates.

Walsh’s legacy, meanwhile, carries on.