The Russian Navy still outnumbers and outguns the Ukrainians in the northern Black Sea. Despite the dominance on paper, the Russian Navy is on its back foot after several successful attacks from the smaller Ukrainian forces.

The Oct. 29 attack on Sevastopol, in which uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) with unmanned aerial vehicles attacked Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, appears to have pushed them further into the shell of their naval bases. Both of their Admiral Grigorovich-class frigates, the largest and most capable ships after the sinking of Slava-class cruiser RTS Moskva (121), have mostly been in port. One of these, Black Sea flagship Admiral Makarov, is believed to have sustained some damage during the October attack.

The increased defenses after the September discovery of a likely Ukrainian uncrewed surface vessel near Sevastopol do not appear to have been successful. During the larger attack on Oct. 29, several of the USVs penetrated the harbor. Drone’s eye footage released shows them operating near the warship piers deep inside the base. Russian reports that the drones reached Pivdenna Bay suggest that they got close to the submarines. A single Kilo-class submarine was present at the time, USNI News understands.

The floating boom defenses around the main warship quay have been pulled across in front of the line of warships, according to satellite imagery. The refueling piers, deeper inside the harbor, also have floating booms deployed. The use of these booms is still intermittent, but the Russians are deploying them more than they had previously.

The change in operating patterns goes further than the frigates. Certain coastal patrol areas, which have until now been under the jurisdiction of the Federal Security Service, or FSB, border guard, now appear to have Russian Navy vessels. Missile corvettes have been seen patrolling where lighter-armed FSB patrol ships used to patrol, according to ship spotters

Sevastopol has been the Russian Navy’s main base in the war and the home of the bulk of the Black Sea Fleet, its headquarters and its flagship. While this is still the case, there is assets have also shifted to Novorossiysk. This base, which has been expanded and improved in recent years, has been a hub for the non-Black Sea Fleet warships which were brought in as part of the build-up for the invasion. The Black Sea Fleet’s four improved-Kilo class submarines are increasingly seen there instead of in Sevastopol. But Novorossiysk is much further away from the action and Sevastopol has remained the hub.

It is difficult to gauge how long the heightened state of readiness will last in Sevastopol following the Oct. 29 attack. The Russian Navy has so far been slow to adapt and has been operating continuously since the start of the invasion of Ukraine.

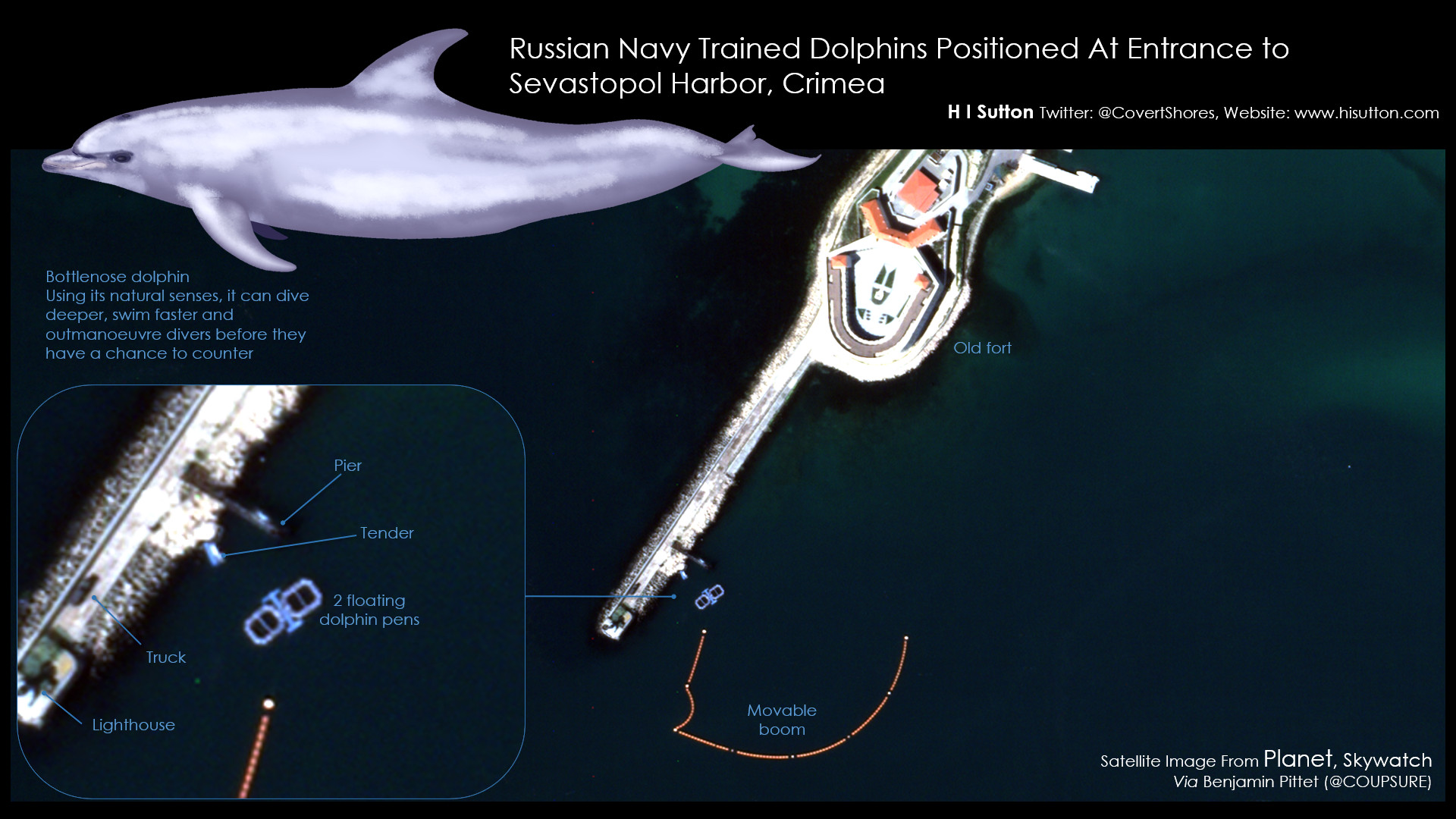

For the first months of the war, Sevastopol appeared unreachable for the smaller Ukrainian Navy, but Russian forces did implement some defensive measures. The Russians deployed combat dolphins to the harbor entrance to guard against Ukrainian divers and beefed up their air defenses were. But overall the base appeared normal, almost complacent. High-value warships, including Moskva, continued to use their peacetime berths. And the boom across the harbor entrance was mostly open.

The situation changed in the summer, and particularly after the September discovery of the USV near Sevastopol. It was a cross between a canoe and a jet ski and was armed with explosives.

That the USV could make it to Sevastopol, apparently undetected, was a wake-up call for the Russian Navy. Damien Symon, an independent defense analyst, noted that the boom across the harbor entrance, normally open, was suddenly routinely closed. And, in late September, the Russians arranged a new boom along the side of the main warship berths. This net, which appears aimed at underwater threats, protects the row of warships from a flank attack. It can also extend to cover the front of the row of warships.

For a time, the number of dolphin pens at the harbor entrance increased from two to three. These do not defend against USVs, but would deter Ukrainian divers from attempting sabotage missions. A rotation of the animals or an increase in their patrols could account for the increase.