NAVAL BASE SAN DIEGO, Calif. — The government’s prosecution against a young sailor accused of arson, which ultimately destroyed an amphibious warship in 2020, centers on one shipmate’s claim he saw that sailor where the fire started shortly before it was reported.

That’s the picture Navy prosecutors painted last week during Seaman Recruit Ryan Sawyer Mays’ general court-martial on charges of aggravated arson and hazarding a vessel. A conviction on the latter charge carries a punishment of up to life imprisonment.

Trial judge Navy Capt. Derek Butler heard testimony from nearly two dozen sailors, investigators and experts over the past week. On Monday, defense attorneys got their shot to convince the judge that Mays is not guilty and that the Navy’s case rests on a questionable investigation that lacks convincing evidence of arson and ignores other potential causes of the fire. The case is expected to wrap up by the week’s end.

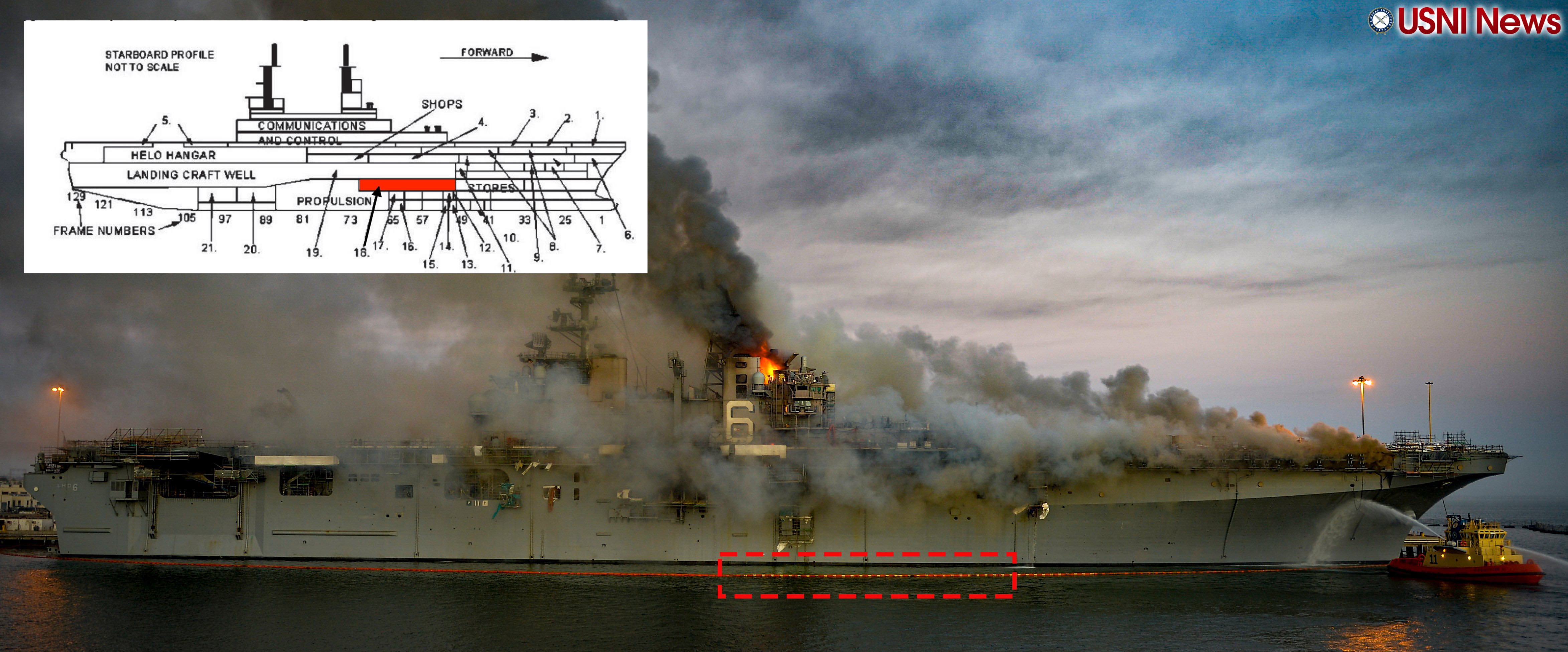

The fire began aboard USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) at about 8 a.m. on July 12, 2020, and burned for five days. The blaze is among the Navy’s costliest, destroying the amphibious assault ship just as the ship neared the end of a $249 million modernization to accommodate the F-35B Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters multi-mission jet. Contractors with NASSCO, a shipbuilding company contracted to do the maintenance availability, hadn’t yet signed the ship back to the Navy, but sailors living in a berthing barge had begun to move back aboard.

Navy officials ultimately decided not to repair the ship – an estimated $3 billion loss – and sold it for scrap.

A sweeping command investigation into the fire pointed to suspected arson as a cause, based on the criminal investigation conducted by Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The investigation also highlighted widespread failures, inaction and inadequate training by the ship’s leadership and crew, revealed significant gaps in command relationships and found serious gaps and shortfalls in capabilities for fire suppression and fire attack.

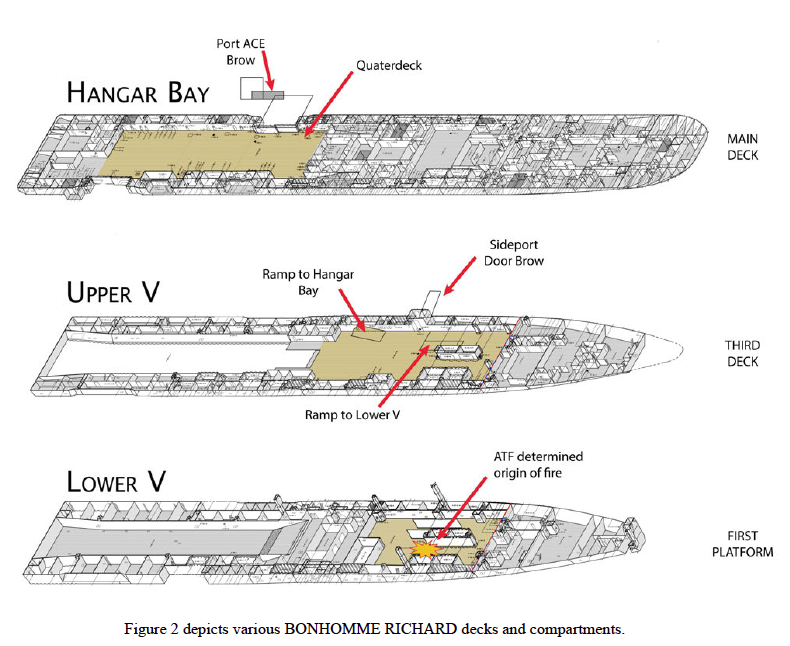

Blaze Began in Lower Stowage Deck

Four days into the fire, ATF fire investigators with a national response team began to examine the ship’s damaged, sooted hull once the onboard fires abated. They zeroed in on an area in the ship’s lower vehicle stowage deck where they believed the fire began around 8 a.m. and shortly after duty section turnover. NCIS and ATF agents questioned dozens of the ship’s crew and collected scores of questionnaires ATF had provided them, and they sifted through debris recovered from the Lower V. Agents then cast eyes on a handful of sailors, including Mays, who they suspected of intentionally setting the fire.

Prosecutors last week arranged testimony that placed Mays in the vicinity of the Lower V, which on the weekend of the fire was packed with a mix of cardboard boxes, buckets, hoses, coils, scaffolding, forklifts and other equipment and trash. One sailor described it as “a junkyard.”

ATF Special Agent Matthew Beals, a certified fire investigator, led the agency’s report into the “origin and cause” of the fire. A 21-year veteran of the ATF, Beals said he’s investigated 225 fires over his career, and upon hearing of a Navy ship aflame at the naval base, the San Diego-based agent testified that he offered NCIS the bureau’s services.

NCIS “deferred the origin-and-cause portion (of the investigation) to ATF,” Beals said when testifying Sept. 20.

In his investigation and inspection of the ship’s Lower V deck, the agent said he believes the fire began when someone put a flame to a petroleum distillate liquid applied on thick, cardboard boxes known as “triwalls.” That fire, he concluded, spread to other items in the space.

Capt. Jason Jones, a Navy prosecutor, asked if any liquid accelerant was found at the site. None was found, Beals said, adding that it could have evaporated or been consumed in the fire. He believes a flame, potentially from a lighter or a match, was used to set the fire intentionally. He based the analysis in part on a series of field tests done in January 2021, six months after the fire. Beals also acknowledged that the contents of a metal pail he found in the Lower V were not collected and analyzed.

“I didn’t feel it warranted sending it to the lab,” he said, adding that its contents were “already contaminated.”

The investigation had noted a sailor who reported seeing someone – alleged to be Mays – walking in the Lower V with a bucket in their hand within a half-hour of the fire being reported.

He ruled out any accidental ignition, such as from an electrical malfunction from forklifts or lithium-ion batteries that were in the space or a discarded cigarette, all of which Mays’ attorneys have raised as potential causes of the fire.

A Second Look at Batteries

ATF’s origin-and-cause investigation, finalized in January 2021, however, did not include detailed inspections or scans of the Li-ion batteries. Defense attorneys during Mays’ Article 32 preliminary investigation hearing in December 2021 raised the batteries as a possible source of arcing, creating a spark that led to the fire. Subsequent inspection of eight batteries that Beals believed to be those ATF photographed in the Lower V after the fire were collected in December 2021 – 17 months after the fire – and taken by Beals to the National Fire Lab in Maryland. The agent testified that after CT scans of the batteries, the ATF “eliminated” them as the cause of the fire.

Beals also dismissed two forklifts near where the fire began as culprits in the fire. He testified that ATF’s experts disagreed with Mays’ experts that arcing had occurred in the engine space of one of the forklifts. Federal investigators did no further inspection of the forklifts.

“They were left in place in the Lower V,” Beals testified.

Defense attorneys raised the possibility that a malfunction in one of the forklifts led to arcing that started the fire. But ATF electrical engineer Michael Abraham, testifying for nearly three hours on Sept. 21, said what the defense’s expert claimed was arcing in the forklift was just a “globule” of melted copper. Copper melts at 1,985 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We considered all potential sources of ignition,” said Abraham, who was part of the National Response Team assigned to the Bonhomme Richard fire investigation.

He said he visually inspected both forklifts and determined the globule would not have caused the fire, nor would the Li-ion batteries that he examined at ATF’s lab, he added.

But in cross-examination by Lt. Cmdr. Jordi Torres, one of Mays’ attorneys, Abraham acknowledged that he hadn’t included the Li-ion batteries in five pages of notes he took from his post-fire inspection aboard Bonhomme Richard, although he recorded seeing 9-volt and other batteries among the debris. He disagreed with the attorneys’ contention that internal damage or ruptures inside batteries could have started a fire.

Mays’ defense attorneys this week are expected to call their own experts in electrical engineering to testify and chip away at the government’s arguments and raise reasonable doubt of the allegations against Mays.

A Sailor’s Accusation

Personnel Specialist 2nd Class Kenji Velasco, one of several sailors who testified on Sept. 22, told the court that it was Mays who he saw in the Lower V deck, wearing a mask and carrying a pail, before the fire was reported.

Velasco’s identification has been questionable. Velasco was more confident in identifying who he spotted that morning than in eight previous times he spoke with NCIS and ATF investigators, defense attorneys noted. In his initial interviews with agents, Velasco hadn’t identified the person he saw by name, but he eventually suspected Mays after discussing it with several other deck department sailors.

Operations Specialist 3rd Class Andrew Cordero testified that he and several others spoke with Velasco in the days after the fire about what they did and saw that morning. During those conversations, they started to think that Mays might have been the one who Velasco told them he saw go down to Lower V. They discussed what that person was wearing, and the “boot camp coveralls” that Velasco described he saw was something that they’d seen Mays wear previously.

“You all started thinking, Seaman Mays?” Lt. Tayler Haggerty, a defense attorney, asked Cordero. “Yes,” he replied.

Mays’ attorneys contend that he was wearing coveralls that morning, not the Type III working uniform. Petty Officer 2nd Class Ray Smith testified that he would have seen Mays during the 7:45 a.m. muster on the flight deck and he said he would have chewed him out if he wasn’t wearing coveralls since “I don’t like people mustering in Type IIIs.” Smith recalled first seeing smoke about 15 minutes after muster.

Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Beau Benson, recalled to the stand on Sept. 23 by prosecutors for a second time, testified that Velasco “was fixated on one person” and had asked him what time he, as a deckplate supervisor, had given Mays an assignment following muster.

“He was just fixated on him in particular,” he said.

BHR Sailors’ Recollections

Eight sailors, all Bonhomme Richard crew members at the time of the fire, took the stand on Sept. 19 to recall what and who they saw the morning the fire began. Nearly 140 of the 1,000-person crew were on duty, according to the Navy’s investigation, and 10 minutes elapsed after smoke was first spotted before the fire was reported

Benson testified that he was standing near the top of the ramp to the Lower V when he saw white smoke, and he reported it to the officer of the day.

Senior Chief Brian Six heard the 1MC call and hustled to the hangar bay, where he saw “bellowing black smoke.” The veteran sailor said “it wasn’t like electrical smoke” but was “almost like petroleum.” He heard “a lot of popping and crackling, and you could hear the roar of the fire.”

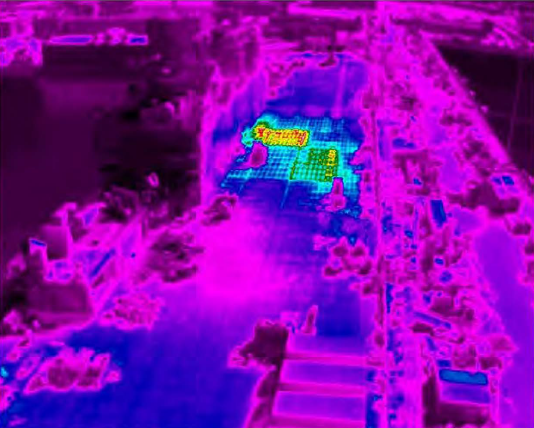

Carrying a firefighting thermal imager as he tried to go down the ramp to the Lower V around 8:30 a.m., Six recalled high heat emanating from the bulkheads and visibility just “two or three inches in front of my face.”

Photos taken by Chief Jason February in the initial firefighting efforts show increasingly thick, dark smoke pouring into the ship’s vast hangar bay – coming up the ramp from the Upper Vehicle deck that’s above the Lower V – in the first half-hour after the fire was reported. Teams of firefighting sailors gathered in the hangar bay and later were joined by federal and local firefighting crews before two explosions two hours later forced evacuation from the ship.

“There was no visibility whatsoever down there,” Damage Controlman 3rd Class Nelson Ernesto PablosGarcia testified.

He was pulling roving duty when he heard alarms go off sometime before 8:10 a.m. and was told to check it out. He told February “to sound battle stations” and he ran to get equipped with a SCBA mask before trying to get down to the Lower V. Heat from the fire, though, kept preventing him from reaching the landing.

Damage Controlman 1st Class Jeffrey Garvin was on duty as a fire marshal when he heard a report via the ship’s 1MC speakers of “black smoke” in the Lower V. Garvin testified he ran up to the hangar bay “and I see smoke bellowing out … black, thick, very dark.”

Garvin said he was pushed back by smoke in an attempt to go down the ramp.

“It was intense smoke. Super hot. It was something I’d never felt before,” he testified.

He saw an “orange glow” and described an “excessive heat and inability to breathe.”

In cross-examination by defense attorney Torres, Garvin said that he tried to get down to the Lower V on his own initiative to try to make sure no one was down there. He was visibly upset , recalling how he couldn’t do it.

“You’re supposed to make sure everybody is safe,” he said.

Sarcasm or Confession?

The judge also heard testimony on Sept. 23 from two sailors who had escorted Mays between the NCIS office at the San Diego base and the military brig located at Miramar Marine Corps Air Station in San Diego. Mays was driven to Miramar, where he would be held in detention for several months, after some 10 hours of interrogation by NCIS and ATF investigators.

Prosecutors argued that statements the detained Mays made while he was in an office at the San Diego base awaiting a medical exam amounted to a confession.

Senior Chief Master-at-Arms Jeremy Kelley testified that he heard Mays say “‘I’m guilty I did it,’ or words to that effect.

In questioning by Torres, Kelley said “you could hear his frustration. He sounded frustrated.” He conceded that he had told NCIS that it was possible that Mays was being sarcastic.

When Cmdr. Leah O’Brien, a prosecutor, asked Kelley if Mays’ tone had changed from the casual conversation during the drive from the naval base, he said “it was very different” and added, “I took it seriously.”

Master-at-Arms 1st Class Carissa Tubman testified that Mays became less chatty and less “playful” as he sat six feet away, waiting to be taken to the doctor.

“At that point, he was a little nervous. He kind of sat there quiet,” Tubman said. “He was mumbling under his breath… I heard, I’m guilty I guess I did it. It had to be done.”

Mays had enlisted in May 2019 and completed the Pre-Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL program at Great Lakes Naval Training Center, Ill., on Sept. 30, 2019. He reported to the Naval Special Warfare Training Center in Coronado, Calif., as a BUD/S student and, during his second attempt at the course, had voluntarily dropped just days into the first week of the first phase. He left Coronado on March 3, 2020, and reported to Bonhomme Richard two weeks later. He’s been assigned to Amphibious Squadron 5 in San Diego since April 2021.

Mays’ sour attitude came from frustration after dropping from BUD/S and assignment to Bonhomme Richard as an undesignated seaman, according to testimony and the investigation. Mays often talked about returning to the training course and openly complained about the deck department and shipboard duty and cursed out the “fleet Navy,” sailors recounted.

Senior Chief Boatswain’s Mate Michael Simms, testifying on Sept. 21, described Mays as cocky, disrespectful and unhappy with doing grunt work, like painting and cleaning, as a member of the ship’s deck department, but in cross-examination acknowledged that “it’s not the most glamorous job in the Navy.”