CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. – A board of officers convened this week to determine whether the officer who led the infantry battalion involved in the fatal 2020 sinking of an Amphibious Assault Vehicle should be discharged from the Marine Corps or allowed to continue to serve.

Lt. Col. Michael Regner, a 19-year combat veteran, was removed as the commander of Battalion Landing Team 1st Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, in October 2020, a few months after eight Marines and one sailor died off San Clemente Island, Calif.

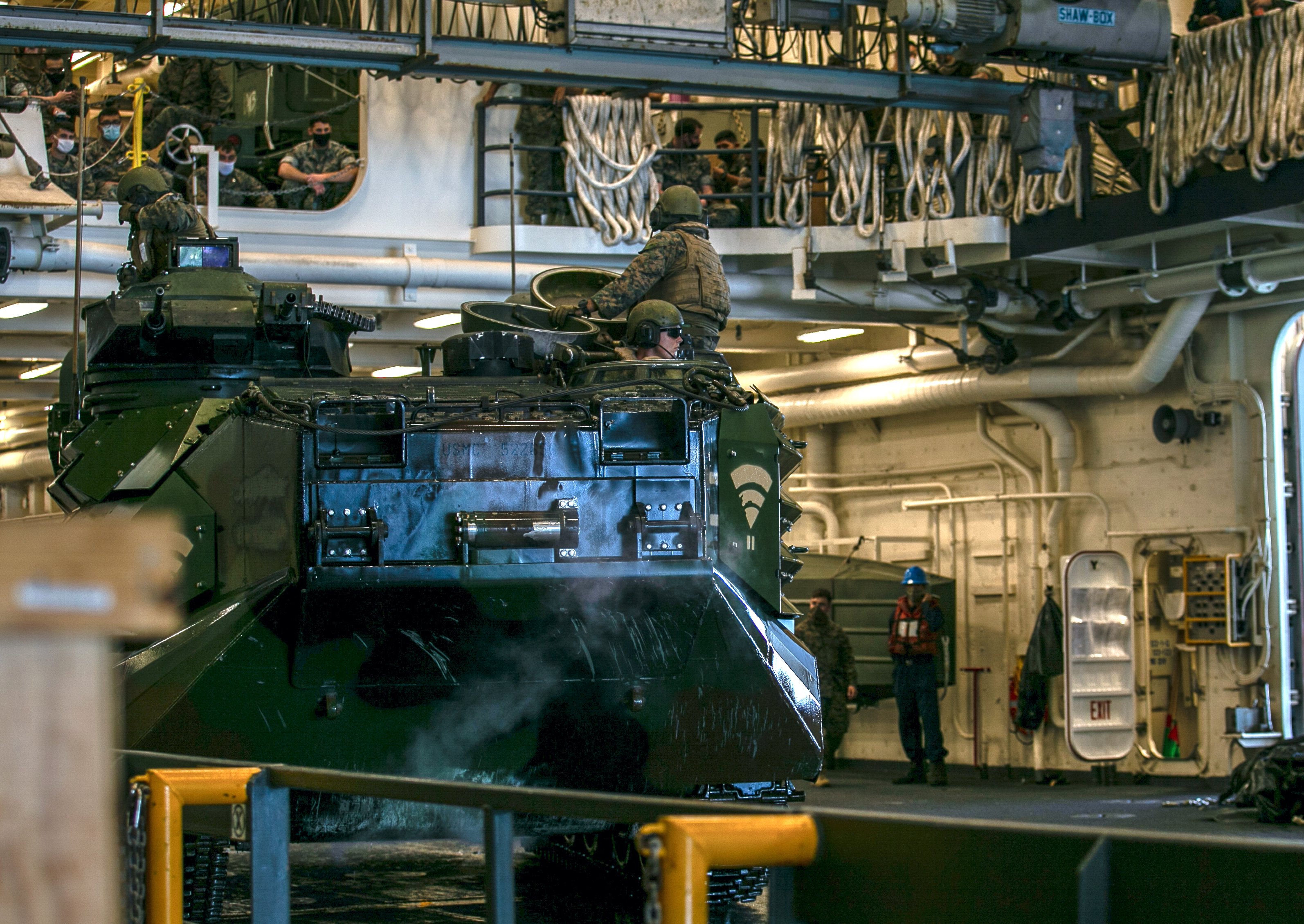

They were among 16 inside the AAV returning to amphibious transport dock USS Somerset (LPD-25) on July 30, 2020, when water began seeping into the 26-ton vehicle and then sank. Eight Marines, including the three-man AAV crew, escaped before the vehicle sunk, but one infantryman later died at a local hospital.

Killed were Navy Hospitalman Christopher Gnem, 22, of Stockton, Calif.; Cpls. Wesley Rodd, 23, of Harris, Texas, and Cesar Villanueva, 21, of Riverside, Calif.; Lance Cpls. Marco Barranco, 21, of Montebello, Calif., Guillermo Perez, 19, of New Braunfels, Texas, and Chase Sweetwood, 19, of Portland, Ore.; and Pfcs. Bryan Baltierra, 19, of Corona, Calif., Evan Bath, 19, of Oak Creek, Wisc., and Jack Ryan Ostrovsky, 21, of Bend, Ore.

Three colonels comprise the “board of inquiry” ordered by I Marine Expeditionary Force commander Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl. They are sorting through reams of documents and will hear testimony later this week to recommend whether Regner should stay in uniform or be discharged for substandard performance. The final actions rest with the deputy commandant for manpower and reserve affairs or the Navy secretary.

“Sixteen inside. Only seven made it out alive. These are the names of the nine who didn’t,” McDonald, who as the board recorder is leading the case for the government, said before stating the names of the deceased. The parents of three of the victims sat in the modest courtroom during Tuesday’s short proceedings before the board recessed to review extensive documents provided as exhibits from the government and Regner’s defense attorneys.

The government contends that Regner ignored several “red flags” as his battalion and its mechanized AAV platoon prepared to train with the Marine Expeditionary Unit and the at-sea integration training with the Navy.

Maj. Michael McDonald, the board’s recorder who is leading the government’s case, noted that a review of the I MEF command investigation characterized Regner’s performance as “a significant departure” of what’s expected of a battalion commander in three key areas: preparation, planning and execution.

The hearing “is not to punish. It is not to point fingers … and not to Monday-morning quarterback,” McDonald said in his opening statement, but “to decide whether Lt. Col. Regner has the potential for future service in the Marine Corps.”

“It is going to be a difficult decision for you,” he told the board. “The bottom line is Lt. Col. Regner’s substandard performance set the conditions for the sinking of the amtrac last summer.”

But a defense attorney argued that “there is no legal basis for separation in this case” because Regner hasn’t been cited by the Marine Corps for any misconduct.

Regner owned up to his responsibility during an earlier counseling session and “never shirked that responsibility” as the battalion commander, Maj. Cory Carver argued to the board. “He never dropped his pack. He’s been working hard. … He knows that he’s responsible for the deficiencies that took place,” he said.

Carver said Regner’s focus continued even after I MEF had offered the option of retirement rather than a board of inquiry. But retiring wasn’t an option, as Regner wasn’t eligible for the 20-year retirement.

Training Shortcuts Cited

The Marine Corps’ investigations found that BLT 1/4 fell short in adhering to training standards and operating procedures in several areas that may have contributed to the sinking and the deaths. Among those cited is that some of the passengers in the amtracs on the mission that day lacked the required water safety training. Some hadn’t met the required water safety qualification, others hadn’t done any training at-sea in the amtrac and others just couldn’t swim well.

McDonald cited a number of failures on Regner’s part in the months prior to and in preparation and execution of the raid exercise. “The bottom line is Marines in BLT 1/4 were not properly swim qualified” and hadn’t received the underwater egress training that was required for such waterborne training, he said. Moreover, McDonald argued, the battalion went ahead with the raid mission without sufficient time training with the vehicles in the water. “You’ve got to start somewhere,” he said. “But you don’t go from crawl to run.”

McDonald took note of Regner’s failures to plan and ensure the proper safety boats were part of the mission, and he said the battalion’s planning was deficient, noting that some of the AAVs were returning to Somerset with passengers they picked up on San Clemente Island, including the Recon platoon, and often without life preservers or being accounted for on manifests.

The unit that day suffered from “get-there-itis,” he argued. “The temptation is to push, to get there … regardless of what normally would be safety considerations.”

But Carver said that Regner was aware of and tracked the water egress qualifications of BLT 1/4’s members.

But Regner was told by the Bravo Company commander that the unit was fully qualified, even though it later became known that some of the crew failed to meet the standard for water safety, the attorney told the board. “Is he legally responsible … for that failure?”

I MEF’s existing policy at the time, Carver said, provided alternatives for Marines and sailors to qualify with smaller underwater egress trainers if the amphibious egress trainer wasn’t available. In early and mid-2020, the amphibious egress trainer was down for maintenance, and demand was high for any other available trainers. But after the sinking, he noted, I MEF revised the policy to require the proper level of egress training.

Regner is likely to testify in his defense to the board.

Condition of AAVs

Regner’s battalion received 14 AAVs that were mostly obtained in degraded conditions from 3rd Amphibian Assault Battalion, which is also located at Camp Pendleton.

“We’re not pulling any punches here. There’s a lot of hands in the pot here,” McDonald said. Regner “inherited bad AAVs.” But the onus was on Regner to ensure that the AAV platoon had completed and passed a critical Marine Corps combat readiness evaluation, which wasn’t done. “That’s a red flag,” he argued.

But Carver told the board that Regner had actively tracked the progress of the maintenance work that eventually got the vehicles operational. The poor materiel condition of the vehicles wasn’t unusual, he noted, and “the Marine Corps [has known] of these problems for years.”

As for the mechanical issues with the mishap AAV, “other Marines are being held accountable … for actual misconduct,” noted Carver. “But that is not this case.”

That remark refers to Lt. Col. Keith Brenize, who was in command of 3rd AA Battalion when he provided the amtracs to Regner’s battalion in spring of 2020 ahead of their training with the 15th MEU. Heckl, in an endorsement to the Marine Corps’ command investigation completed in May, found that Brenize’s actions “had a direct bearing on the cause of this tragic mishap.”

Brenize, a combat veteran who enlisted in 1994, handed over command in June 2020 before heading to the Marine Corps War University. Last month he faced his own retention board at Quantico, Va. That board met Dec. 6 through 10 and was in recess “until early 2022,” a Marine Corps Training and Education Command spokesman told USNI News.

The sinking – one of the Marine Corps’ worst in recent years – prompted the Marine Corps to order changes to training and maintenance. The service, which plans to replace the amtracs with the Amphibious Combat Vehicle, temporarily banned most AAVs from conducting waterborne operations until its decision last month to permanently end any water operations.