This post has been updated with additional information on the administrative action taken by the Navy and Marine Corps.

A Navy-ordered investigation into the service’s role in the 2020 fatal sinking of a Marine Corps amphibious assault vehicle that killed nine found faulty assumptions, confused command roles and communications, conflicting policies, gaps in amphibious warfare training and certification, deficient doctrine, and poorly maintained vehicles.

Senior commanders reviewing the investigation determined those shortfalls had no direct bearing on the cause of the mishap. Still, the Navy is moving ahead with implementing a series of revisions to how the Navy and Marine Corps train for and conduct amphibious warfare, – including in shore-to-ship movements – which senior leaders believe will make such operations safer.

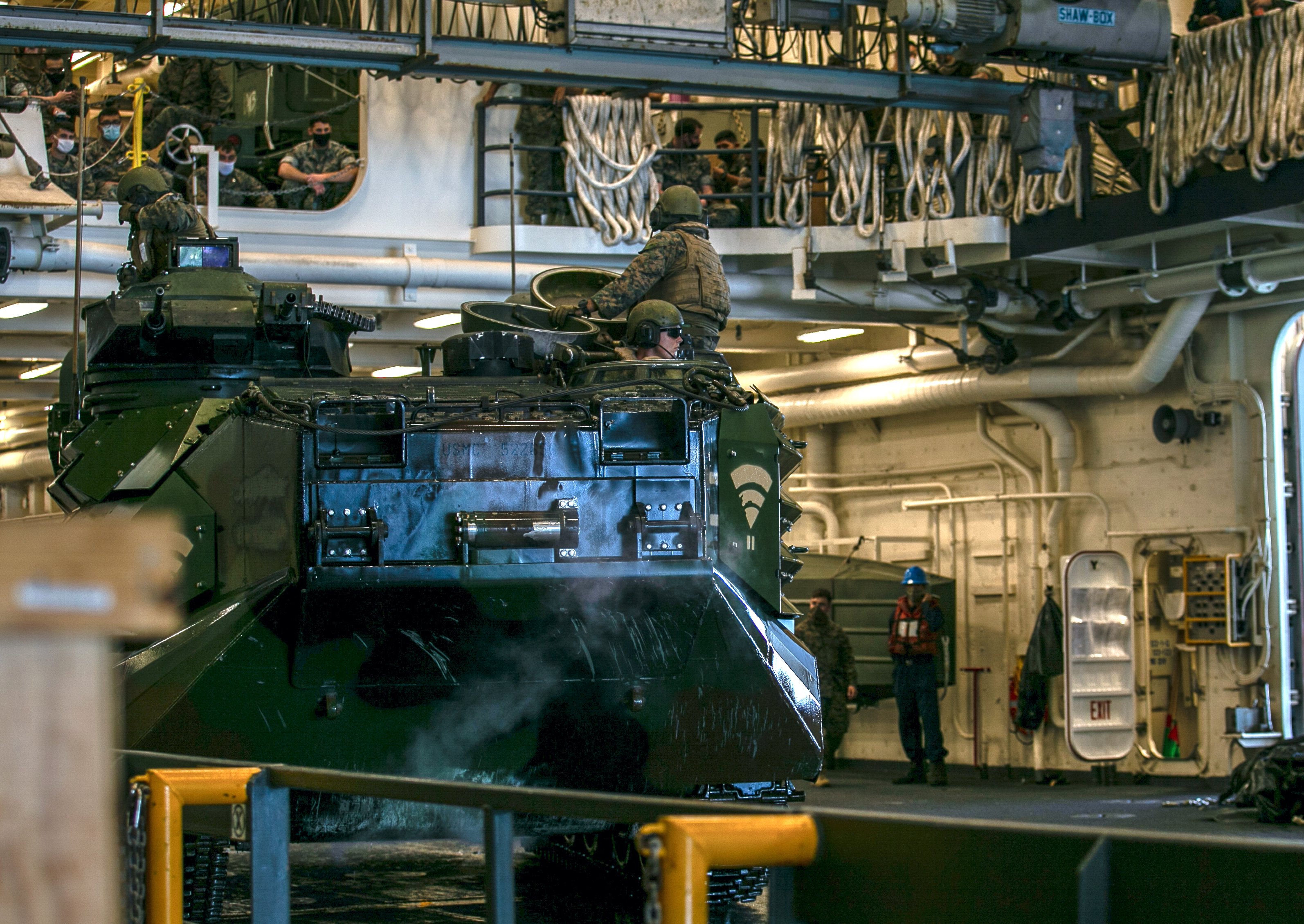

Eight Marines and one Navy corpsman in the AAV died when the 26-ton vehicle sank after taking on water while they returned to USS Somerset (LPD-25) after their unit completed an amphibious raid on San Clemente Island on July 30, 2020. Seven other Marines in the vehicle were rescued and pulled onto other amtracs loaded with Marines, as there was no designated, empty safety boat with them at the time.

“This tragedy should have never happened,” Vice Adm. Roy Kitchener, commander of Naval Surface Forces and Naval Surface Force Pacific, said during a media call this week briefing the investigation’s results.

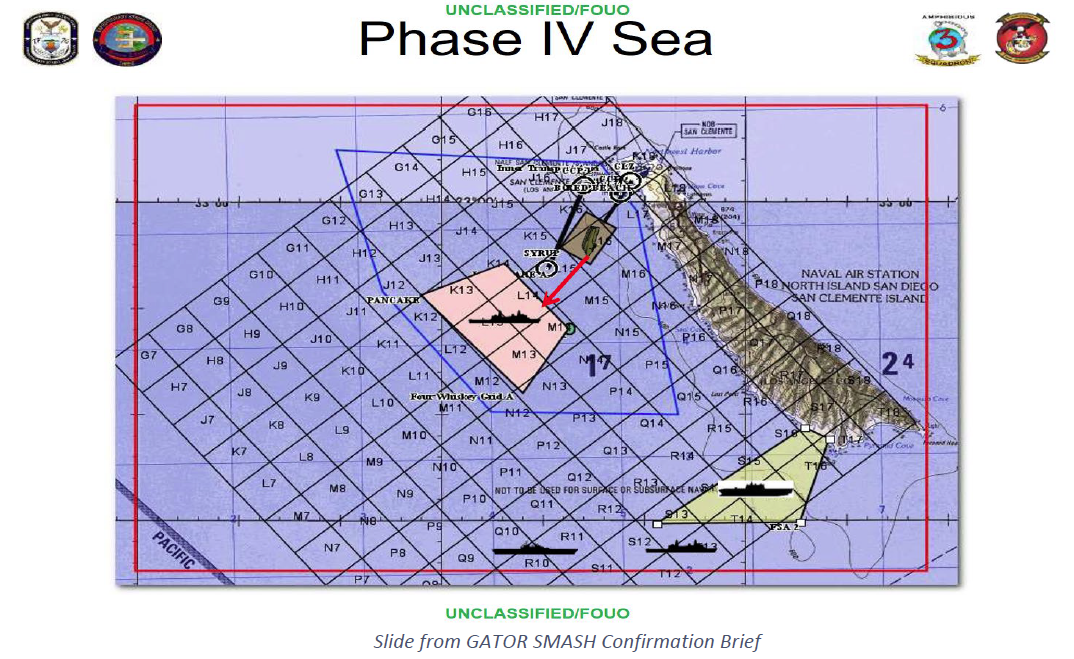

The sinking happened during “Operation Gator Smash,” a mechanized amphibious raid during the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit’s first at-sea, integrated training exercise with their Navy counterparts with the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group led by Amphibious Squadron 3.

The Marine Corps’ command investigation into the sinking, released in March, blamed a “chain of failure” over seven months, including poor safety measures and a “combination of maintenance failures, due to disregard of maintenance procedures, AAV crewmen not evacuating personnel when the situation clearly demanded they be evacuated, and improper training of embarked personnel on AAV safety procedures.”

That investigation also noted communication confusion among Navy personnel and Marines on Somerset about safety boats and the AAVs’ return to the ship that were delayed by mechanical issues that then complicated the ship’s other missions that afternoon.

Vice Adm. Stephen Koehler, commander of U.S. 3rd Fleet in San Diego, Calif., received the completed investigation on June 4 for his review. “I conclude the issues addressed within this investigation were not causal or contributory to the sinking,” Koehler wrote June 22 in forwarding the investigation to U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Samuel Paparo, with several changes to the report’s recommendations.

The Navy’s latest investigation largely concurs with the Marine Corps’ initial investigation and doesn’t reveal any significant new findings. “The Navy and the Marine Corps investigations established that poorly-maintained AAVs, inadequately trained personnel and the failure to conduct a timely egress caused the sinking of the AAV and the tragic loss of life,” Paparo said in his July 2 endorsement of the command investigation, which he submitted to the vice chief of naval operations.

Among the changes ordered so far is the tightening of requirements for designated safety boats. “To ensure a more rapid response capability, safety boats are now required whenever AAVs operate with Navy shipping,” Paparo wrote in his endorsement submitting the report to Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. William Lescher.

The incident took the lives of Navy Hospitalman Christopher Gnem, 22, of Stockton, Calif.; Cpls. Wesley Rodd, 23, of Harris, Texas, and Cesar Villanueva, 21, of Riverside, Calif.; Lance Cpls. Marco Barranco, 21, of Montebello, Calif., Guillermo Perez, 19, of New Braunfels, Texas, and Chase Sweetwood, 19, of Portland, Ore.; and Pfcs. Bryan Baltierra, 19, of Corona, Calif., Evan Bath, 19, of Oak Creek, Wisc., and Jack Ryan Ostrovsky, 21, of Bend, Ore.

“Their tragic deaths remind us of the dangerous duty performed by the members of our all-volunteer force, and of the vital responsibility of leaders to identify and effectively address risk inherent in military service,” Paparo wrote.

No Clear Accountability

The investigation, Paparo wrote, also determined “the actions and inactions on the part of Somerset were not fully in accordance with doctrine and established procedures, and the investigation identified gaps in our doctrine and procedures.”

“Unless otherwise directed, I intend to take administrative action in the cases” of the commander of the amphibious task force (CATF), Somerset‘s commanding officer, and the ship’s tactical action officer, Paparo wrote. The CATF was the commander of Amphibious Squadron 3, Capt. Stewart Bateshansky.

The Navy has not stated publicly what specific actions, reliefs or punishments were taken or if any are pending against those three officers or anyone else involved and tied to the events of that day.

“I think we’ve identified some things that we didn’t do so well, and we’re working on that” Kitchener said during the media call to discuss an overview of the reports’ findings. The Navy “took adminstrative actions on some officers involved.” He declined further details.

Senior Marine Corps leaders, in the immediate aftermath of the deaths and in the year since the mishap, fired several officers, including top leaders with the 15th MEU, to include the MEU commander, Battalion Landing Team 1/4 commander, BLT 1/4’s Alpha Company commander and AAV platoon commander. Some actions are still pending, Maj. Gen. Gregg Olson said in the media call, but he also declined to provide specifics.

Olson also declined to specify actions but noted that a number of officers in the 15th MEU’s command chain “all suffered some sort of adverse, adminstrative action. Some of those actions are still ongoing.” In addition, the former commander of 3rd Amphibian Assault Battalion, who while in command provided the AAV Platoon and vehicles to the 15th MEU’s detachment, also “has been exposed to adverse, admninistration action, which is ongoing at the time,” he said, speaking broadly about the Marine Corps’ actions to date.

The Navy and the Marine Corps have not levied any charges, under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, in connection with the mishap, the officers said.

The AAV’s vehicle commander, who the investigations all cited, failed to order the Marines and sailor to evacuate the ill-fated amtrac in sufficient time. The commander survived the sinking. It’s unclear what, if any, adverse actions were levied.

The Investigation

At congressional hearings in May, Navy officials told lawmakers that the service was conducting the investigation to look at “a few questions unanswered” by the Marine Corps’ investigation. The intent was “to understand what actions and decisions that Navy personnel made that day could have contributed to the tragedy, and then what policies and practices may be required and must be improved,” Kitchener testified.

At congressional hearings in May, Navy officials told lawmakers that the service was conducting the investigation to look at “a few questions unanswered” by the Marine Corps’ investigation. The intent was “to understand what actions and decisions that Navy personnel made that day could have contributed to the tragedy, and then what policies and practices may be required and must be improved,” Kitchener testified.

The investigation focused on “the U.S. Navy’s role and its interaction with the Marine Corps” in six key areas, wrote Rear Adm. Christopher Sweeney, who authored the report:

- Communications, decisions and actions by Navy personnel in the waterborne AAV operations.

- Communications between Navy and Marine Corps personnel before, during and after the sinking.

- The command-and-control relationships and established Navy doctrine.

- Sea-state conditions the day of the mishap.

- Somerset‘s location, movement and operations that day.

- The approval process and the number and types of safety boats involved in the operations.

The investigation, ordered by San Diego-based U.S. 3rd Fleet, began in April. Sweeney, a surface warfare officer who commands Everett, Wash.-based Carrier Strike Group 11, led the 16-member investigation team that included Marine Col. Trevor Hall.

Already, the Navy is moving along to implement some changes, officials said.

The Navy is revising its at-sea integrated training known as PMINT, or PHIBRON-MEU Integration Training, evolutions “to ensure schedule of events is appropriate with the ‘crawl’ stage” in the training of amphibious ready groups and Marine expeditionary units, the investigator recommended. He also recommended the Maritime Working Group form a focus group, by Aug. 1, to make recommendations to shape the basic, advanced and integrated phases of ARG/MEU training.

In addition, the latest updates to the “Wet Well Manual” – CNSP/CNSL 3340.3E – should incorporate the new safety boat requirements, improve blue-green radio communications among the Marine Corps and Navy during amphibious vehicle operations, standardize pre-splash briefs, and clear up who has authority to approve water launches.

Other changes are underway to five other Navy and Marine Corps reference documents: NTIP 3-02.1M Ship-to-Shore Movement; MCTP 3-10C Employment of Amphibious Assault Vehicles; Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations; U.S. Fleet Forces Navywide OPTASK AMPHIB DTG 111354Z JAN 17, and NAVMETOCCOMINST 3144.1E Manual for Weather Observation.

The Navy provided a redacted copy of the 39-page report to USNI News and several journalists ahead of the public release, but hundreds of pages of supplementary documents collected by the joint Navy-Marine Corps investigative team were not released.

The Navy is also publicly releasing a command investigation by the Marine Corps that specifically looked at how the 15th MEU and its subordinate units were composited and prepared for the PMINT. A redacted, 35-page report of the investigation, also released, was submitted May 19 to the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps by the investigator, Lt. Gen. Carl E. Mundy.

Bad Comms, Briefing Gaps Cited

The investigation found, among other issues, important omissions in confirmation briefs, including the identification of hazards with AAV launch, recovery and waterborne operations and the AAV operation’s scheme of maneuver. There also was confusion throughout the day on who had “positive control” over the amtracs during waterborne operations.

The inadequacy of the mission confirmation brief “left in doubt the roles and responsibilities” of various officers and created a “confusion of authority” regarding the splashing and recovery of the Marines’ amtracs, Kitchener said.

Investigators found no Navy instruction or a clear process that determined who held that “PCO” role and was to approve any AAVs entering the water for return from the beach to Somerset.

The ship’s tactical action officer and surface warfare coordination, they wrote, “both located within [the combat information center], were surprised when the AAVs went feet wet and were unaware of prior permission that was communicated by the SOM Watch Supervisor to the AAV Wave Commander over Boat Alpha,” which is the ship’s primary radio comms with the AAVs. The secondary radio circuit available is Boat Bravo.

The Marines had given only Somerset personnel “estimated times to splash” from San Clemente Island back to the ship, they wrote, and that vagueness combined with hours of delay in returning to the ship further complicated Somerset‘s own scheduled and emergent taskings.

The ship’s commander “believed that as the PCO he did not have the authority to abort or delay splash back to the SOM from SCI. His attendance at the confirmation brief caused him to believe the authority to delay or abort splash and apply go/no-go criteria from SCI was the responsibility of the RFC” or the Marines’ raid force commander.

Somerset’s captain and officer-of-the-deck also “were surprised when the AAVs splashed back to the ship, and were alerted to their return by the OOD visually seeing the AAVs in the water,” investigators noted. Both officers “were unaware of prior permission” that the ship’s watch supervisor relayed to the AAV wave commander via Boat Alpha.

Investigators also wrote that the ship’s captain “reported that the ship did not subsequently launch safety boats for the AAV recovery because the AAV Platoon did not request them. He believed that the AAV Platoon would provide the same two empty AAVs he believed launched as safety boats” earlier in the day.

“The AAV Platoon Commander did not designate a safety boat for the extraction phase because he believed SOM would provide a safety boat per the original confirmation brief,” they noted.

Chaotic Comms

As they prepared to launch from San Clemente Island back to the ship, the Marines’ raid force of 13 amtracs began grappling with AAV mechanical troubles.

The bulk of the raid force command stayed at West Cove with three other AAVs to await repairs to a downed vehicle while the rest returned to Somerset. The ship already had canceled a scheduled replenishment to accommodate the amtracs’ late shore-to-ship return and was grappling with the need to land a helicopter requiring refueling.

The group of nine AAVs left the beach at about 4:50 p.m., for the ship. But a half-hour later, one vehicle, “Amtrac 3,” suffered a “malfunction” that lost steering and started taking on water, so it was towed back to San Clemente Island. The PHIBRON and Bateshansky, as the CATF, “was aware that one AAV was rigged for tow and returning to SCI,” the report noted.

The remaining seven amtracs continued toward Somerset, which was several miles off the beach and had sped up to prepare for air operations, when water began to seep into “Amtrac 5,” or AAVP7 SN 523519.

Meanwhile, communication lapses, garbled radio calls and confusion among Marines and Navy personnel continued on the water, ashore and on Somerset – particularly about which and how many AAVs were experiencing problems or were towed back to the island and at what level of water incursion Marines must evacuate the amtrac.

“According to the H&S Company Commander, there was confusion on the ship as to which AAV was in distress,” stated the Navy investigation, which incorporated statements and documents from the Marine Corps’ initial command investigation. “There were simultaneous decisions about which AAV was taking on water, how much water it had taken on and which AAVs were trying to get back to SCI versus trying to return to the ship.”

In fact, the 1/4’s Bravo Company commander returned to Somerset on Amtrac 6 but didn’t know about Amtrac 5’s situation and thought the only troubled AAV was the one that had returned to San Clemente Island, the investigation noted.

Safety Boat Concern

Meanwhile, more water seeped into Amtrac 5, rising from ankle depth to bench to chest-high level, before the vehicle commander ordered all the passengers to evacuate. Some managed to get topside as another vehicle, Amtrac 14, reached them. But before everyone could get out, a wave swept over the water-ladened amtrac, and it sunk at about 6:15 p.m., eventually settling 385-feet deep.

Koehler, in his endorsement of the investigation, disagreed with the investigator, who wrote that Somerset’s commanding officer “had the authority to determine an AAV could be used as a safety boat.”

“I find the lack of a Navy safety boat did not cause or contribute to the loss of AAV 5,” Koehler wrote. “The effect that a Navy safety boat would have had is speculative.”

He said Amtrac 14 still would have been the first to reach that troubled AAV, “particularly if the Navy safety boat was in company with AAV 3 as it was being towed. “Based on the overall circumstances at the time, it is unlikely that having a Navy safety boat in the water would have better prevented this tragedy.”

Koehler noted that at the time of the mishap, “shore-to-ship movement was not addressed within training or certification. As a result, there is no guarantee the training and certification during Amphibious Warfare (AMW) Basic Phase would have left the leadership better prepared to execute shore-to-ship movement.”

The Navy hopes to close those gaps. One of the recommendations is the inclusion of shore-to-ship movement in amphibious warfare training and certification. Another recommendation would require the five-week Senior Amphibious Warfare Officer’s Course for all prospective commanding officers.

The investigation noted that Somerset‘s commanding officer, executive officer, plans and tactics officer, and tactical action officer weren’t aboard the ship when it completed AMW basic phase certification, held in October 2018. “Certification requirements for AMW include an evaluated ship-to-shore movement of AAVs as well as ship-to-shore movement for LCACs and LCUs,” the report noted, but not recovery of amtracs.