A command investigation into the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit – the Camp Pendleton, Calif.,-based force that lost nine members when their amphibious assault vehicle sank training at sea last July – has been completed and is pending review by the acting Navy secretary, the Marine Corps commandant said Wednesday.

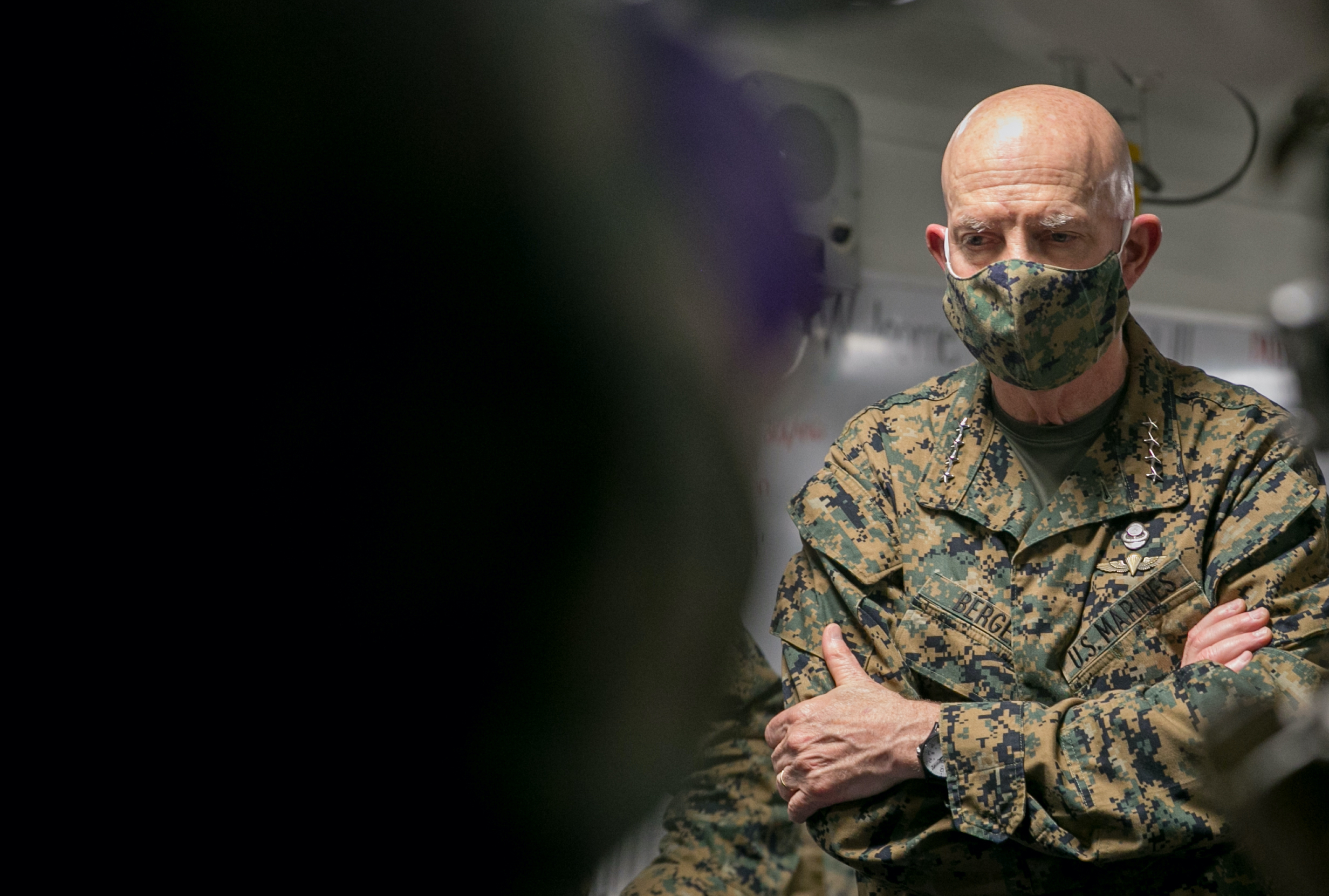

Berger said he has reviewed the investigation, which began in early April and was completed nearly two weeks ago. Earlier this week, Berger had an initial discussion with Acting Navy Secretary Thomas Harker before both men will sit down to discuss it further, “which I will do pretty quickly.”

“I have a very clear picture right now, all the way up the chain,” Berger said during a media roundtable to update the investigations and actions in the aftermath of the July 30, 2020, fatal mishap off California. The Marine Corps’ initial suspension of all AAV waterborne operations with Navy ships ordered in the aftermath remains in effect, he added, pending reviews, reconciliation and alignment between Navy and Marine Corps procedures and directives.

The Marine Corps has not yet announced additional administrative actions or punishments against any personnel, including senior general officers, which Berger said was “to be determined.”

“I can’t step into the middle of an investigation, or I’d jeopardize the whole process,” he said when pressed about families’ concerns that senior leaders haven’t been fully held responsible for what happened.

Berger said the initial command investigation, which was released publicly on March 26, and the unreleased safety investigation found “sufficient detail to answer the question of what directly caused that amtrac to sink and those Marines and that sailor to lose their lives.”

“But there were unanswered questions, still, on different levels about how the actions leading up to [the mishap]… and what could we learn might prevent a similar tragedy in the future,” he said.

The Marine Corps, as of yet, has not said whether anyone has been criminally charged under the Uniform Code of Military Justice for their actions or inactions related to the mishap.

Berger suspended one senior leader – Maj. Gen. Robert Castellvi, the 1st Marine Division commander at the time of the mishap – from his position as the Marine Corps’ inspector general earlier this month pending the outcome of the 15th MEU investigation. A key issue the initial command investigation cited against Castellvi was that he, as the division commander, hadn’t ensured the ill-fated AAV unit had done all required training, including water egress training, and passed the Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation before it composited to the MEU.

The focus of the 15th MEU’s investigation is on “everything that led up to the” mishap in three main areas, Berger said: How the 15th MEU composited, what “leadership decisions centered on the materiel condition of those amtracs,” and the training that’s required for Marines and sailors who were doing the scheduled training exercise “and answer the questions of who made what decisions to do what” prior to the incident. The investigation “looks at it through the lens of” the 1st Marine Division and the division staff as well as the 15th MEU and I MEF commanders at the time, he said.

MEUs, which fall under the three-star-level Marine expeditionary forces, composite units from various battalions, companies, platoons and squadrons belonging to a Marine division, air wing or logistics group. The initial command investigation found that a serious chain of failures up and down the chain of command led to the AAV’s sinking and the deaths of eight Marines and one Navy corpsman. At least eight officers, to include leaders with the 15th MEU and Battalion Landing Team 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, were relieved of command or received unspecific administrative action, and the command investigation recommended possible action review against the former commander of 3rdAmphibian Assault Battalion, which sourced the mishap AAV and platoon.

“It’s very clear to me… that the sinking of the amtrac and the loss of the Marines and sailor both were preventable,” Berger said.

“The best way that we can honor that is to do everything that’s humanly possible to try to prevent something like that from ever happening again,” he said, adding that “we can never promise that it won’t ever happen again, but we can certainly do all that we can to limit the likelihood that it ever happens again.”

Berger, in providing journalists with updates on the investigations, spoke about the safety culture and offered personal thoughts about the mishap, which ranks among the worst fatal, at-sea accidents in recent memory.

Blue-green training shortfalls

The AAV, carrying Marines and a platoon corpsman assigned to Battalion Landing Team 1/4, sank as it was returning to amphibious transport dock ship USS Somerset (LPD-25) after an amphibious raid training exercise on San Clemente Island during the 15th MEU’s first at-sea training with the Makin Island Expeditionary Strike Group.

A separate, parallel, related investigation by 3rd Fleet into the actions and responsibilities of the Navy units – they fall under Expeditionary Strike Group 3 – involved began May 3 is still underway. “I don’t know when it will be done,” Berger said, but added, “I think it’s pretty far along.”

Among the factors that the initial command investigation blamed in part on the deaths of the Marines and sailor were the AAV platoon and BLT’s lack of training with their amtracs at sea and with amphibious ships, as well as the failures to ensure that all individual- and unit-level training requirements had been done. Investigators noted these led to unfamiliarity with standard operating procedures and practices, including the improper briefings and delayed response and order for the embarked personnel to exit the amtrac soon after it began taking on water. The amtrac sunk in 385 feet deep with half the personnel still inside the 26-ton vehicle.

Despite detailed instructions and directives that dictate required waterborne and amphibious training, “in that particular case, not all were followed,” said Berger.

“The minimum required training was not done,” he said, in response to a USNI question about the AAV platoon’s lack of waterborne training at the time. The waterborne training the amtrac platoon and BLT 1/4 had done at the time “was not where we wanted it to be.”

The initial investigation laid bare that Marines have fewer amphibious ships available for them to train with so they can hone their seagoing skills to conduct amphibious operations. For many, the scheduled, at-sea, composited training with often scripted scenarios are the only times they work with their Navy counterparts and train together to do those missions before a MEU deploys overseas with the Navy ESG.

Today’s amphibious fleet is only about one-third of what Berger had access to when he was a young lieutenant. “We don’t have the number of ships, and their maintenance isn’t allowing us to get on ship with the frequency that we need to do,” he said.

“Access to ships, the availability of ships, absolutely is key here. That’s the second reason, over the past 20 years, that I think our bench of expertise… has thinned,” he said, adding “we need to rebuild that bench.”

New blue-ribbon panel

Berger announced the Marine Corps also will convene an independent panel to look broadly at amphibious operations, specifically “where are we now – the Navy and the Marine Corps – and then, based on how do we need we’re doing to need to operate in the future, what is it going to take to get us there.”

Retired Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, a former 15th MEU commander, has been assigned to lead the panel, which will include retired Marine Corps and Navy leaders long experienced in amphibious operations. Berger said it will focus on “what we need to learn as an institution to make sure that, in the years to come, we know how to do what is our core competency.”

“It’s pretty clear to me after I read the first two investigations… that there were broader institutional issues that we had to tackle,” he said.

The panel will include retired Marine Corps and Navy leaders long experienced in amphibious operations. Berger said it will focus on “what we need to learn as an institution to make sure that, in the years to come, we know how to do what is our core competency.”

They will first determine “where are we right now. How deep is our bench? How competent are we on the Marine Corps side? How competent are they on the Navy side?” he said, noting the crew, commanders and leaders on the amphibious ships. “Just exactly how competent are we? A real, no-kidding assessment, how deep is that bench of expertise, of proficiency? And look at where we must go – I’m talking about four, five, six years into the future, of how the Navy-Marine Corps thinks it needs to operate… which still involve amphibious operations, and a lot of it.

“What do we need to do to get to from where we are now to there? Is that structure changes, is that training changes, and on the Navy’s side. What do we need to do to get to where we have to? It’s a broad mandate, and I think it will get adjusted over the next three months. But first begin with a baseline of where are right now… Where are we relative to what we say we should be able to do and how much experience we actually have, on both the Navy and the Marine Corps side, and help us see a path forward to get us where we need to go.”

The panel’s work “will take several months,” he added. Details of the panel’s members and direction haven’t yet been finalized, a Berger spokesman, Maj. Eric Flanagan, told USNI News.

Berger and other senior officials have sounded alarms about the continued loss of experience in amphibious operations stemming from two decades of a Marine Corps largely focused on land-based operations mostly in Afghanistan, Iraq and, more recently, in Syria. “That pool has shrunk,” he said, “largely because of the emphasis on operations in the Middle East,” he said, “so our bench is thinner than I’m comfortable with it being so we have to expand that.”

“I think this separate panel, separate review, I think is going to help us get there,” he added.