The first LPD Flight II amphibious warship is still in the early stages of construction, but the Marine Corps is already eyeing a more lethal replacement for the ship.

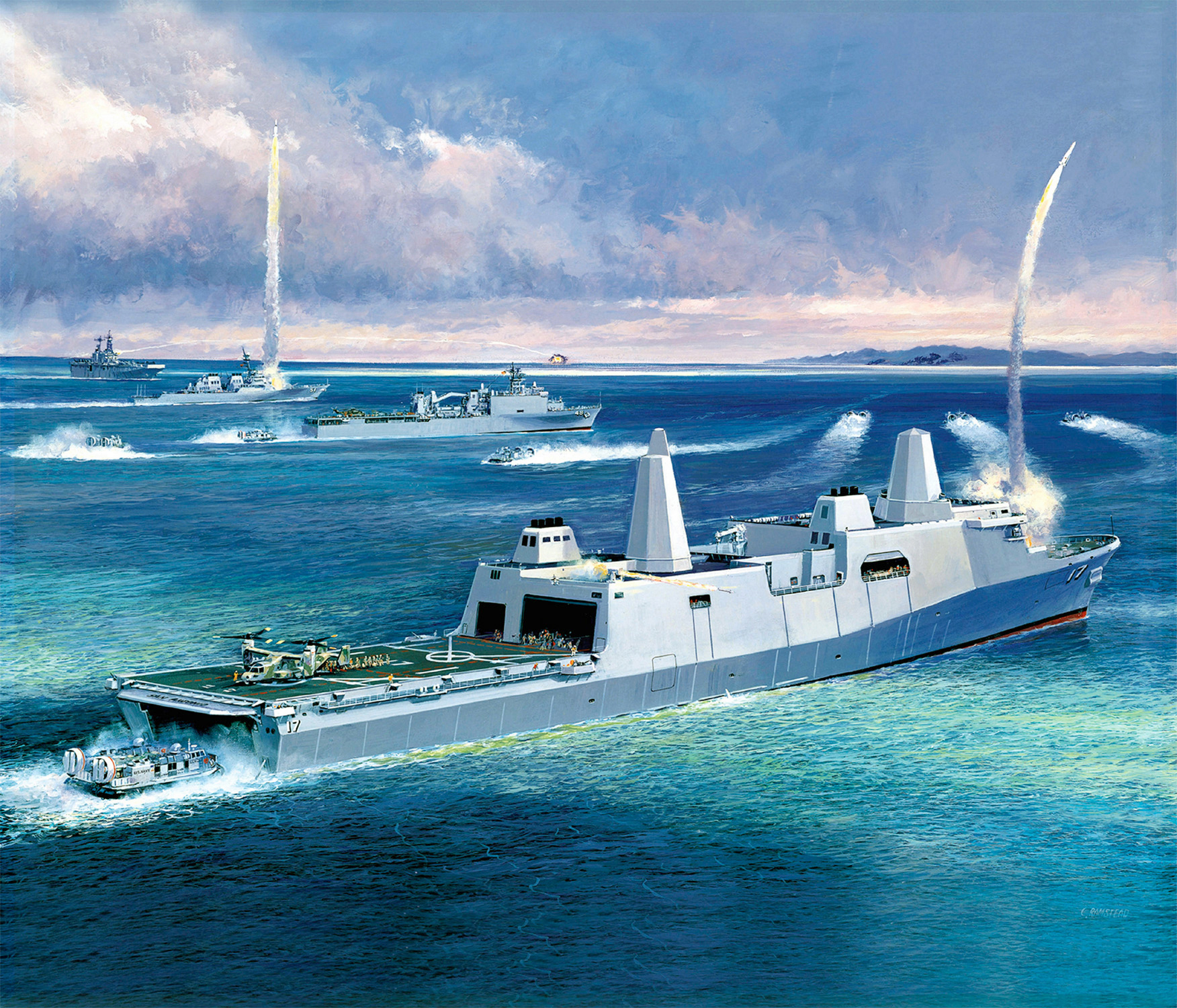

The Navy-Marine Corps team was meant to get a big boost in capability when the services decided that a slightly modified San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock (LPD-17) would replace the aging Whidbey Island-class dock landing ships (LSD-41/49) – the LPDs have much greater command and control capability, a sophisticated medical ward and significant internal space for vehicle maintenance and other needs.

Yet the lack of offensive firepower on the ships has been a point of discussion in recent months, and the Marines are putting down a marker in an annual update to the Force Design 2030 document that Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. David Berger released today.

The document states it is “time to begin seeking a replacement for the LPD-17 Flight II whose fundamental design elements were conceived more than 25 years ago. We must answer the question – What is LXX? While we do not have an answer to that question yet, we do know that the most lethal capability on a non-big deck amphibious ship of the future cannot be the individual Marine.”

Brig. Gen. Eric Austin, the director of the Capabilities Development Directorate under the deputy commandant for combat development and integration, told USNI News that the Marine Corps would make do with the LPD Flight II but is already in talks with the Navy about how to field something better suited for the kind of peer-adversary littoral fight the Marines are preparing for.

“As the Commandant considers the force required to keep pace with the threat, it is never too soon to consider what capabilities we need to adapt. LXX represents a vision for an all-domain amphibious warfare ship networked into the fleet fighting system – lethal and survivable. We will continue to work in concert with the Navy on their requirements for the 30-year shipbuilding plan,” Austin said in a statement to USNI News.

“In its current form LPD flight II, along with LPD 17 Class and LHA, will offer fleet commanders flexible and versatile amphibious warfare ships to meet the requirements of a complex distributed maritime operations environment.”

Austin did not comment on how quickly the Marine Corps hoped to see work done to better understand LXX requirements and start looking at designs. The current Navy shipbuilding plan calls for 13 LPD Flight II ships to be built, with the ship acquisition effort spanning through 2034, but if the Marines push for a quick resolution to the LXX effort then that could potentially truncate the LPD Flight II line.

This concern about lack of lethality comes after Maj. Gen. Tracy King, who until recently served as the expeditionary warfare director on the chief of naval operations’ staff (OPNAV N95) – the lone Marine general heading a branch of the Navy requirements organization – called for the sea services to find a way to boost the lethality of LPDs.

The simplest option he proposed was to “uncoil some of the lethality that’s resident in the [Marine Air Ground Task Force] when we’re in transit, which we traditionally haven’t done,” King said in January.

“Can you think of a better resource to get after countering [a small boat threat] than the rotary wing [close-air support] that comes with a Marine Aviation Combat Element? I mean, the Cobra is a magnificent asset to help protect the fleet, especially when she’s doing close in-shore transit. And we’re doing that on different platforms.”

Somewhat more contentious is asking Marines to use their longer-range weapons – especially once the Marine Corps starts fielding Marine units with Naval Strike Missiles – to conduct sea control operations while in transit on LPDs.

“Going back to uncoiling the lethality of the MAGTF, I see containerized weapon systems that the Marine Corps is using: when we jump onboard a ship, that becomes available to the ship’s captain. So maybe we don’t need to install launchers and NSM; maybe the Marine Corps [expeditionary advance base operations] forces serve as the main battery when we’re moving out,” King said.

“To me, that just makes sense. We give the latitude and the flexibility to that ship’s captain to use those assets when he needs to. There’s been some naysayers to that, mostly in my tribe, because if you use all my missile before I get there, I don’t have my missiles. But I’m a little bit dismissive of that complaint because the ship’s got to get there first. So I think you’re going to see us employing containerized weapon systems that we can use wherever we want to use them.”

On the more complex end of the conversation is actually equipping LPDs with missile launchers. The ships were originally designed with space for Vertical Launching System cells but were ultimately not built with the cells. Ripping up the ship deck to put them in now would likely be prohibitively expensive, but the services could look at more of a bolt-on option with a containerized weapon system. King said in January that the Naval Strike Missile may not be a good option, as the Navy is fielding them on the Littoral Combat Ship now and there might not be enough manufacturing capacity to also build more for LPDs, but he said it was an issue to keep considering.

“The actual material solution is not my concern, which missile we put on the ship. But you heard me say, if it floats it fights. We have these magnificent 600-foot-long, highly survivable, highly capable LPD-17s that, in my humble opinion … I think that the LPDs need the ability to reach out and defend themselves and sink another ship,” King said at the event. He said he didn’t want the LPD to become an offensive surface strike platform but that having anti-ship missiles onboard protects the Marines onboard “because the enemy has to honor that threat.”

In addition to mentioning the LXX notion, the Force Design 2030 update also states that “the development of a robust inventory of traditional amphibious ships, new light ships, alternate platforms, and littoral connectors is required to create a true naval expeditionary stand-in-force and force-in-readiness.”

It notes that “some analysis has been completed on the Light Amphibious Warship that supports conclusions that an inventory of a minimum of 35 ships is required.”

The LAW program is already in industry studies and is set to be awarded to a shipbuilder next year, and has been one of the biggest acquisition initiatives to come out of Berger’s effort to reshape the amphibious force to remain dominant in the Indo-Pacific region into the 2030s and beyond.

Amphibious warfare was one of the first areas Berger tackled when he became commandant in July 2019, calling in his Commandant’s Planning Guidance for the service to ditch its requirement for 38 traditional amphibious ships to conduct a two-Marine Expeditionary Brigade forcible entry operation.

“I do not believe joint forcible entry operations (JFEO) are irrelevant or an operational anachronism; however, we must acknowledge that different approaches are required given the proliferation of anti-access/area denial (A2AD) threat capabilities in mutually contested spaces. Visions of a massed naval armada nine nautical miles off-shore in the South China Sea preparing to launch the landing force in swarms of ACVs, LCUs, and LCACs are impractical and unreasonable,” Berger wrote, raising many eyebrows at the time.

“We must accept the realities created by the proliferation of precision long-range fires, mines, and other smart-weapons, and seek innovative ways to overcome those threat capabilities. I encourage experimentation with lethal long-range unmanned systems capable of traveling 200 nautical miles, penetrating into the adversary enemy threat ring, and crossing the shoreline – causing the adversary to allocate resources to eliminate the threat, create dilemmas, and further create opportunities for fleet maneuver.”