CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. – The July drowning deaths of eight Marines and a sailor who sank with their amphibious assault vehicle off a California island were the result of poor training, a vehicle in “horrible condition,” and lapsed safety procedures in a rush to deploy an operational AAV platoon, according to a command investigation of the incident reviewed this week by USNI News.

The deadly events of July 30, 2020, marked the end of a “chain of failure” that began seven months before, when an AAV platoon belonging to 3rd Amphibian Assault Battalion at Camp Pendleton, Calif., received inoperable amphibious vehicles just a few months before they’d join the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit to train for an overseas deployment, according to the senior investigator.

The battalion “did not properly train or equip this AAV Platoon for a very difficult MEU training cycle and deployment,” the investigator wrote. “They formed the platoon late, the platoon was not properly trained and evaluated to join the 15th MEU, and they were assigned AAVs in horrible condition.”

The mishap was the culmination of a “combination of maintenance failures, due to disregard of maintenance procedures, AAV crewmen not evacuating personnel when the situation clearly demanded they be evacuated, and improper training of embarked personnel on AAV safety procedures,” the investigator wrote.

Additionally, the training off San Clemente Island didn’t have the proper safety procedures in place that could have helped evacuate the crew from the floundering amtrac, according to the investigation.

Navy Hospitalman Christopher Gnem, 22, of Stockton, Calif.; Cpls. Wesley Rodd, 23, of Harris, Texas, and Cesar Villanueva, 21, of Riverside, Calif.; Lance Cpls. Marco Barranco, 21, of Montebello, Calif., Guillermo Perez, 19, of New Braunfels, Texas, and Chase Sweetwood, 19, of Portland, Ore.; and Pfcs. Bryan Baltierra, 19, of Corona, Calif., Evan Bath, 19, of Oak Creek, Wisc., and Jack Ryan Ostrovsky, 21, of Bend, Ore., died from the mishap.

As of Wednesday, two senior commanders cited in the investigation for various failures had been relieved of command by Lt. Gen. Steven R. Rudder, who commands Marine Corps Forces Pacific: 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit Commander Col. Christopher Bronzi was relieved of duty on Tuesday, and Battalion Landing Team 1/4 Commander Lt. Col. Michael Regner was relieved in October. Additionally, according to the investigation report, the I Marine Expeditionary Force commander, Lt. Gen. Karsten Heckl, had fired the Bravo Company commander “for loss of trust and confidence for the reasons generally within” the investigation.

Incident

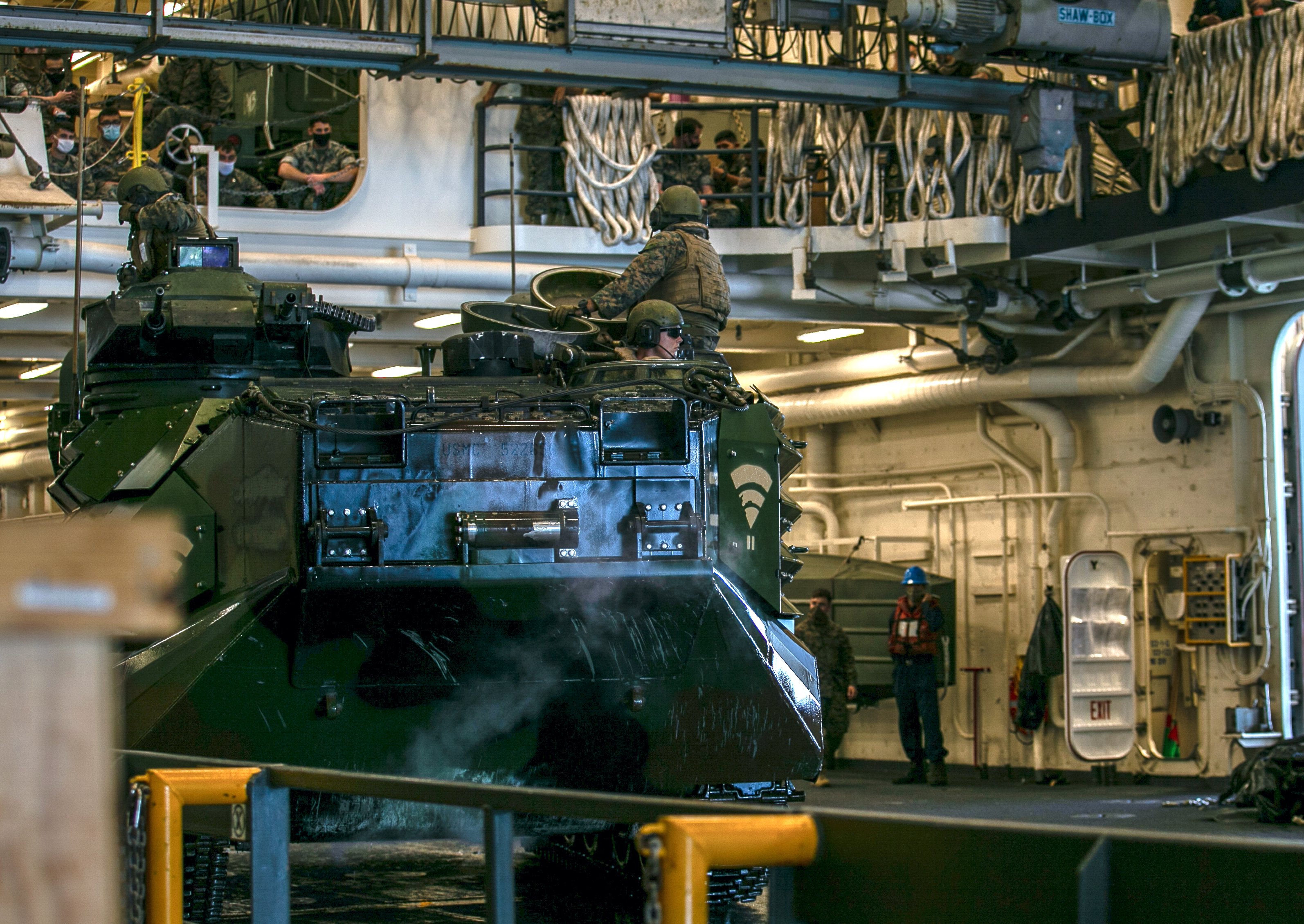

On July 30, 2020, 12 Marines and a Navy corpsman assigned to Bravo Company, Battalion Landing Team 1/4 were crammed inside a 36-year-old amtrac for workups off San Clemente Island off the California coast ahead of the 15th MEU’s upcoming deployment.

After launching from amphibious warship USS Somerset (LPD-25), part of the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group, that morning to the island, the AAV was returning to the ship that afternoon.

The platoon had been struggling with mechanical failures across several vehicles all day. One amtrac remained on Somerset due to a mechanical issue. After landing on San Clemente Island at 8:38 a.m., one of the 13 amtracs blew a hub and required repairs, and Bravo Company and the AAV platoon leaders later decided to remain at San Clemente Island’s West Cove with the broken AAV and three other vehicles.

The remaining nine AAVs left the beach at 4:50 p.m., headed for Somerset nearly three miles offshore. One amtrac lost communications with the ship, and another suffered a malfunction that required another vehicle to tow it.

Two miles from ship, the doomed amtrac — AAVP7 SN 523519 — began taking on water.

After a crewman first reported water inside their amphibious assault vehicle, the vehicle commander gave no order to prepare for possible evacuation, as regulations require, the investigation found.

As water pooled around the combat boots of 13 men inside the old amtrac – its engine, electronics, bilge pumps and sketchy transmission now barely working – the vehicle commander still didn’t order them and his two crewmen to evacuate. When water rose to calf level, he frantically waved a checkered distress flag for 20 minutes before a Marine in a nearby amtrac saw it and radioed their command, nearly a mile away on San Clemente Island, that the AAV was in trouble.

The amtracs loaded with Bravo Company for the waterborne training that day had gone to sea without a proper safety boat, as required, and without the water safety brief all vehicle crews are supposed to give embarked personnel to prepare them to react and escape, if necessary.

Inside the now-darkened hull, water leaking from multiple spots quickly rose to chest level before the vehicle commander – an enlisted Marine – ordered the embarked Marines and Navy corpsmen to evacuate. With their bulky Kevlar cargo vests and some with flotation collars and rifles, they struggled to open a top cargo hatch and get out.

They had lost precious time to escape the 26-ton amtrac.

“The key moment in the mishap was when water was at ankle level… and the vehicle commander failed to order the evacuation of embarked troops, as required by the Common Standard Operating Procedures for AAV Operations,” the investigation officer wrote. “Instead, the vehicle commander was more focused on getting back to the ship, vice evacuating the embarked personnel.”

Nearly 45 minutes after water entered the amtrac, only three Marines had scrambled from a top hatch as the ocean lapped at its edge before a wave swept over the vehicle.

“When the wave swept into (the AAV), the embarked personnel had been standing on the bench seats in order to evacuate the vehicle. The force of the water rushing in knocked personnel off their feet,” causing shock and disorientation, the investigation officer wrote in the report, which he completed Jan. 8. “The embarked personnel were not trained appropriately and did not realize how dire the situation was,” he added, noting most hadn’t shed their combat gear and body armor in the 45 minutes since water first leaked inside.

Water flooded the troop compartment, causing the AAV’s nose to quickly rise and then sink with 11 men still inside at 6:15 p.m. Only three Marines made it to the surface — and only two survived.

Technical inspections and analyses of the amtrac – after it was recovered from a depth of 385 feet of water – revealed some anomalies, loose or missing parts, and worn seals.

“There was not one single discrepancy that caused (it) to sink, but rather a sequence of mechanical failures,” concluded two seasoned AAV veterans with a combined 71 years of AAV experience. They found, among other things, the transmission failed after losing oil due to a loose drain line plug, which led to loss of engine power. Additionally, “the forward hydraulic bilge pump would not have pumped out water due to the low engine speed.”

It got worse as the weakened bilge pump failed. “The rising water levels inside the engine compartment caused the generator belt to cast water out of the engine panel and onto the generator, ultimately causing the generator to fail,” they wrote. That left the AAV “running only on battery power, and the electrical bilge pump was running at a degraded level. The water coming in was far greater than the bilge pump could expel out, as a result, the vehicle sank.”

Sea States and Safety

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, there was much speculation around whether rough seas that day off San Clemente Island played a role.

The investigation found a moderate sea state in the area that day until the amtracs encountered rougher seas leaving the protective West Cove, but at sea state 3 it was within the AAV’s operational window. Still, Rudder cited that anecdotal reports at the time “all support the sea state west of [San Clemente Island] during the mishap was higher than expected, and may have exceeded the no-go decision criteria briefed for the training event.”

Worse, the investigation noted, was that no dedicated safety boats were assigned for the training, in case an amtrac at sea were to need help. Two were required, at least – usually rigid-hull inflatable boats or combat rubber raiding craft, or, if necessary, an AAV without passengers – to enable a quick response and provide space to take on personnel.

But a combination of confusion, bad assumptions and poor communication among the platoon, battalion landing team and Somerset crew resulted in the AAV platoon leaving Somerset and then returning with just one of the loaded amtracs acting as a safety boat. After the mishap AAV started taking on water, one amtrac approached and, after bumping into it, managed to help evacuate a few Marines before the amtrac sank.

“There were no safety boats in the water prior to or during critical moments of the mishap,” Rudder wrote. “It is impossible to establish for certain that a safety boat in the water during the mishap would have prevented the loss of life, but a safety boat likely would have responded more quickly than the approximately 45 minutes it took for the mishap AAV to sink.”

“Considering the mishap AAV commander was waving the November flag approximately 20 minutes, it is likely a safety boat crew would have observed the distress signal sooner, responded more quickly and been better able to facilitate rapid egress and transfer. The mishap AAV commander’s calculus for initiating troop egress may have been different had a safety boat arrived on scene while the water inside the AAV was at boot ankle or higher,” he continues.

Bad Amtracs

Beyond the safety failures and the delay in evacuating the crew from the amtrac on July 30, investigators found critical failures in the mechanical health of the vehicles assigned to the 15th MEU.

The mishap AAV was categorized in 2015 as IROAN — inspect and repair only as necessary. It was one of several amtracs that were in shoddy condition, contrary to training and readiness requirements the Marine Corps expects for its MEUs, Heckl, the I MEF commander, wrote in his Jan. 14 endorsement of the investigation.

“Fully operational and mechanically sound AAVs should have been provided to the 15th MEU the day they composited,” Heckl wrote. “The decision to select AAVs from the deadline lot showed extremely poor judgment. By some accounts, these AAVs had not been operational for approximately one year and were in a very poor state of repair.”

Service-wide inspections ordered after the mishap found “a majority of the AAVs failed to meet the new inspection criteria. The leading causes of failure during these inspections were plenum leakage failures, inoperable Emergency Egress Lighting System, and bilge pump discrepancies. Maintaining the reliability of this platform requires consistent assessment over time to ensure vehicle readiness and safety.”

“Readiness standards in effect prior to the mishap did not accurately account for long-term deterioration in AAV readiness across the Marine Corps over time,” Rudder, the MARFORPAC commander, wrote.

It’s unclear from the investigation reviewed by USNI News why 3rd Assault Amphibian Battalion supplied the platoon with amtracs that were in shoddy condition.

That battalion commander, Rudder said, “knew that his AAV Platoon needed to be ready [join] the 15th MEU in a short timeline, and then left it to that AAV Platoon to try to make the repairs themselves without receiving resources. He had a responsibility to position his AAV platoon for success by ensuring they had the training and equipment required for a complex mission deployed at sea for several months.”

The AAV platoon joined the 15th MEU in April 2020. The report redacted the battalion commander’s name. However, 3rd AA Battalion at the time was led by Lt. Col. Keith Brenize until June 2020, when he left for top-level school and Lt. Col. Wilson Moore became the battalion commander.

Heckl put some blame on the former commander. “The decision he made pertaining to maintenance and training greatly contributed to the overall chain of failures which had a direct bearing on the cause of this tragic mishap,” he wrote. “I find inexcusable the inadequate training of the AAV Platoon prior to [joining the MEU], the overall unsatisfactory state of AAVs that he and his staff designated to be transferred to the 15th MEU (12 of 13 operationally inoperative), the poor timing of that AAV transfer decision in close proximity to CHOP (a matter of weeks), and the insufficient resources he and his staff marshalled to assist the AAV Platoon,” which he said was “underresourced to make those repairs.”

The 15th MEU commander “reasonably believed that necessary corrective actions were being taken,” wrote Heckl. All of the AAVs transferred to the MEU “passed final inspection prior to the… conduct of any operations.”

Heckl wrote he fired Regner as BLT commander “for loss of trust and confidence for the reasons outlined by the [investigation]” and noted that he had “acted consciously and truly attempted to correct the maintenance failures of the AAV platoon once he learned of them. But his leadership oversight and failures in the training areas” noted by the investigator “were significant departures from what is expected of a commander, especially one with his experience.”

Poor Training

The Marines of Bravo Company not only were operating a substandard amtrac, they weren’t prepared to save themselves in case of emergency.

“The failure by the AAV platoon to conduct a thorough splash procedures and embarked personnel safety briefs is a significant piece of evidence that this platoon’s discipline and combat effectiveness were seriously compromised,” the I MEF commander wrote in his Jan. 14 endorsement. “This serious failure of leadership contributed to the overall events that led to the loss of life and injury of many Marines and sailor. This was likely the result of ineffective training and enforcement of [standard operating procedures] and safety procedures at the platoon, company and battalion level within the AA Bn, and it was totally unacceptable.”

Rudder cited multiple failures in two key areas – training and readiness – as contributing factors in causing the mishap and delaying the rescue effort.

The 15th MEU required every subordinate unit to “receive a high level of training and evaluation to meet the MEU’s challenging mission. Had the following training requirements been met as required, the AAV Platoon and embarked Marines may have been better prepared and responded more quickly as the mishap unfolded,” he wrote in his Feb. 25 endorsement of the investigation.

The AAV platoon hadn’t done the required Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation before it transferred to the MEU, a responsibility of the 1st Marine Division commander, Rudder wrote. “Although the failure of the AAV Platoon to conduct a [Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation] was not a causal factor in the mishap, a MCCRE may have exposed the AAV Platoon’s deficiencies in training and readiness identified in the investigation.”

The division, MEU and BLT commanders bear some responsibility for not ensuring training requirements were met, he said. He added the division commander – at the time was Maj. Gen. Robert Castellvi – “is not responsible for any failures that occurred after the MEU composite date and he was not the on-scene commander during the mishap,” so he decided no administrative or disciplinary action was warranted.

He called out the BLT’s inadequate training, particularly with the waterborne AAV operations that are a cornerstone of Marine Corps amphibious capabilities. The mishap happened the first time Bravo Company personnel embarked on AAVs for waterborne operations, he noted. The battalion and MEU commanders “relied heavily on land-specific evolutions to evaluate the readiness of the AAV Platoon and Co B to conduct waterborne operations. Both stated the mechanized raid forces’ performance during land-based evolutions drove their assessments of both units. The confidence of both commanders that proficiency on land would translate to success in waterborne operations was misguided.”

The units also fell short in ensuring all personnel were current with swim and water qualifications, which include training designed to teach and prepare them to escape an accident at sea, Heckl wrote. The Marine Corps maintains several Underwater Egress Trainer systems: the Submerged Vehicle Egress Trainer and the Shallow Water Egress Trainer, as well as the Modular Amphibious Egress Trainer. But eight of the victims hadn’t completed the required shallow water training, which closely resembles the environment of a submerged AAV.