When the Navy moved from a conventionally powered fleet to a nuclear one, Adm. Hyman Rickover oversaw the transitions for decades, remaining in uniform until the age of 82 as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy” to ensure the sea service adopted the new technology in a precise and controlled way.

When the Navy moved to a netted collection of sensors and shooters under the Aegis Combat System, Rear Adm. Wayne E. Meyer was the “Father of Aegis” and oversaw the program for its first 13 years, ensuring his “build a little, test a little, learn a lot” mantra infiltrated the Navy’s entire approach to expanding its surface combatants’ missile defense capability.

Today, as the Navy and Marine Corps are planning a transition into a hybrid manned-unmanned force, the services are big on vision but short on specifics for how they’ll achieve their goals from a programmatic and leadership standpoint – leaving lawmakers uneasy with the absence of a clear parent to guide the unmanned fleet.

The Navy and Marine Corps this week released an Unmanned Campaign Framework meant to serve as a broad outline of their intentions to move forward in developing the hybrid fleet, and today three leaders testified on the plan to the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee. While they brought good news on many of the individual unmanned air, surface and subsurface vehicles, lawmakers voiced their concerns about cross-cutting issues: are mechanical and electrical systems reliable enough for long-term unmanned operations without regular human intervention? Is autonomy software sophisticated enough to allow unmanned craft to operate safely in a range of traffic, weather and sea state conditions? Do the missions of these unmanned systems match the Navy’s most pressing needs?

“Before we begin, I want to dispel any narrative that has taken hold in some quarters that Congress and this committee in particular are universally opposed to unmanned systems and platforms. In fact, some of our most reliable and well known unmanned platforms like the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper programs were a result of direct congressional action despite reservations from the Department,” subcommittee chairman Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) said when kicking off the hearing today.

“We on this subcommittee also recognize the advanced capabilities and the potential impacts unmanned platforms could have on the fleet. We are very supportive of new tasking that could include [intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance], magazine and resupply support, refueling, anti-submarine warfare, and anti-mine operations. Each of these missions could free up manned vessels and allow our sailors and Marines to better focus on pacing threats,” he continued.

“As we head down this new road which includes larger and more complex technology, however, I believe we must incorporate the lessons learned from acquisition challenges like the Littoral Combat Ship and DDG-1000 to avoid costly, repeated mistakes. There must be built-in opportunities for learning between initial research and serial production to ensure we proceed pragmatically and intelligently. Our sailors and Marines deserve reliable and capable platforms to ensure they can remain in the fight.”

Moments later, subcommittee ranking member Rep. Rob Wittman made a similar point, if not more sharply worded.

“I don’t think there is anyone in Congress who doesn’t see the obvious benefits of this unmanned, autonomous capability. But I fear the zeal to deliver the future may lead to waste today,” he said in his opening remarks.

“There is no doubt that our future relies on our ability to expeditiously develop unmanned, autonomous vehicles. But I will not support a misguided acquisition program that wastes taxpayer resources in an effort to deliver this vision. We need to be realistic in our technology assessments, resolute in our desired end state, and adaptable to delivering key attributes of the vision,” Wittman added.

The Navy leadership sought to highlight where it had learned from these past mistakes and how it was seeking to buy down risk with unmanned systems development, through things like land-based testing and racking up significant hours of prototype run-time in the water ahead of buying program-of-record vehicles. The Marine Corps highlighted its unmanned systems as largely being known technologies that were being integrated in new ways, therefore bringing less risk to the table as lawmakers try to understand how to invest in the future of the services while not wasting precious money in tight budget times.

Wittman asked about how things would be different now compared to the Navy’s first big swing at an unmanned surface vessel, the Remote Minehunting System, which the Virginia lawmaker said consumed $700 million and 16 years in a failure that “has endangered our entire mine warfare capability and haunts the Navy five years after its termination.”

Jay Stefany, the acting assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition, told him that “part of our effort now is to build one or two prototypes of something, whatever the capability is we’re looking at, and then get it out and use it, get it into the sailors’ and Marines’ hands so we can see if it’s reliable, if it’s going to meet the intent that we’re looking for. Make sure our engineering community is also heavily involved in making sure it really will have the tried and true capability and reliability when we get it out there. And if we see a need, potentially do both land-based as well as at-sea testing of whatever that capability is before we come back to a formal program decision and actually start building in quantity. And I think taking that pause to make sure we actually have the sailors and Marines operating and getting their feedback – did it do what we really wanted it to do? And make sure the engineers have a say in there, that it’s not just technologists, it’s the engineers saying yeah, that actually could work and will be reliable. So we’re going to put that into our practices: we have things called gate reviews and program reviews where we’re bringing the senior technical authority and others in as well as the fleet in to make sure we’re reviewing that kind of information before we make program decisions to go forward.”

Wittman responded, “I think that’s key: get it in the hands of sailors and Marines, get it in the hands of the fleet, let them push it and try it and figure out what works and what doesn’t, use digital twin technology to get immediate feedback and make changes. I think that’s exactly the path we need to be on.”

Even if the Navy has learned its lesson on good programmatic development – back to Meyer’s “build a little, test a little, learn a lot,” which was quoted multiple times during the hearing as it relates to unmanned prototyping ahead of committing to programs of record – lawmakers expressed great concern about the Navy’s ability to properly define what capability it wants and successfully go after that requirement.

This was most evident in the carrier-based aviation portfolio. The Navy has taken multiple bites at the apple over the years to develop an unmanned carrier-based strike platform – only to settle on an unmanned carrier-based refueling aircraft in the MQ-25A Stingray program. The Navy said when it kicked off the Stingray program that it wanted to learn the basics of safely operating an unmanned aircraft on and around an aircraft carrier with a lower-risk but still important portfolio – mission tanking, with some limited ISR capability – before investing more into an unmanned strike platform.

Already three and a half years after the Navy released its final request for proposals to industry for the Stingray program, lawmakers expressed their doubts that the Navy was progressing enough in carrier-based unmanned aviation and that it was ignoring the requirement for high-end warfare missions such as strike or electronic attack that would be more useful in a fight against an adversary like China.

Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities (OPNAV N9), said during the hearing that the Navy had wrestled with how to prioritize the missions for its unmanned carrier-based platforms but that ultimately it couldn’t risk “chasing that very high-complex mission before I do the foundational building-block approaches to integrating these vehicles in the air wing.”

“My view is, we need to introduce those capabilities with successive, increasing levels of complexity to complement the air wing that we have today,” he said. Once the Navy masters launching and recovering the unmanned aircraft, moving it around the flight deck and hangar bay, and getting air wing personnel comfortable with a hybrid force, the service could move beyond an unmanned tanker and add new missions – perhaps leading to nearly half the future carrier air wing being unmanned.

Kilby said electronic attack would be a good next mission to pursue: an unmanned aircraft accompanying a manned jet could, when prompted by the pilot, go into enemy territory to jam a system ahead of the manned aircraft flying in, for example. ISR would be another, if the unmanned aircraft could stay in the air for 12 hours or longe and far exceed the endurance of manned planes.

“I don’t want to sign up for that before we’ve met some of these rudimentary things to integrate capability in the air wing, and I think the MQ-25 is our way to start that integration” Kilby added.

There was much less pushback from lawmakers on the Marines’ plans, which largely revolve around finding new maritime missions for existing unmanned craft, or integrating existing platforms and weapons with autonomy software to create new unmanned or remotely operated capabilities – pointing to the lawmakers’ claims that they’re not against unmanned systems in general but rather have concerns about the Navy’s ability to reduce technological risk before fielding in large numbers.

Lt. Gen. Eric Smith, the deputy commandant for combat development and integration, said at the hearing that the three primary unmanned systems the Marines are pursuing would “fit together to deny certain sea spaces to an adversary in order to enable fleet maneuver,” but they also come with less risk because they are “all basic technology today that we are simply integrating” in new ways.

The Remotely Operated Ground Unit Expeditionary (ROGUE) Fires vehicle, for example, is a Joint Light Tactical Vehicle stripped of its armor and crew cabin, altered to be remotely operated, with a Naval Strike Missile strapped on top, Smith said. The ROGUE vehicle can be operated via a controller or through a LIDAR system that allows for a follow-the-leader operation. In either case, “it’s paired as a manned-unmanned teaming setup. Picture an artillery unit that is firing a HIMARs, the High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System, but now firing a Naval Strike Missile. That vehicle paired optimally – one manned vehicle, three robotic vehicles with the command vehicle – would be inserted and is transportable via our organic means” such as sling-loaded under a CH-53K heavy lift helicopter, carried inside a KC-130 airplane, or lifted on a surface connector or amphibious ship.

The ROGUE Fires setup, which puts enemy ships at risk for more than 100 miles, “is an existing platform: Joint Light Tactical vehicle, no new technology. Naval Strike Missile: no new technology. We simply integrated two existing technologies, and that’s how we buy down the risk.”

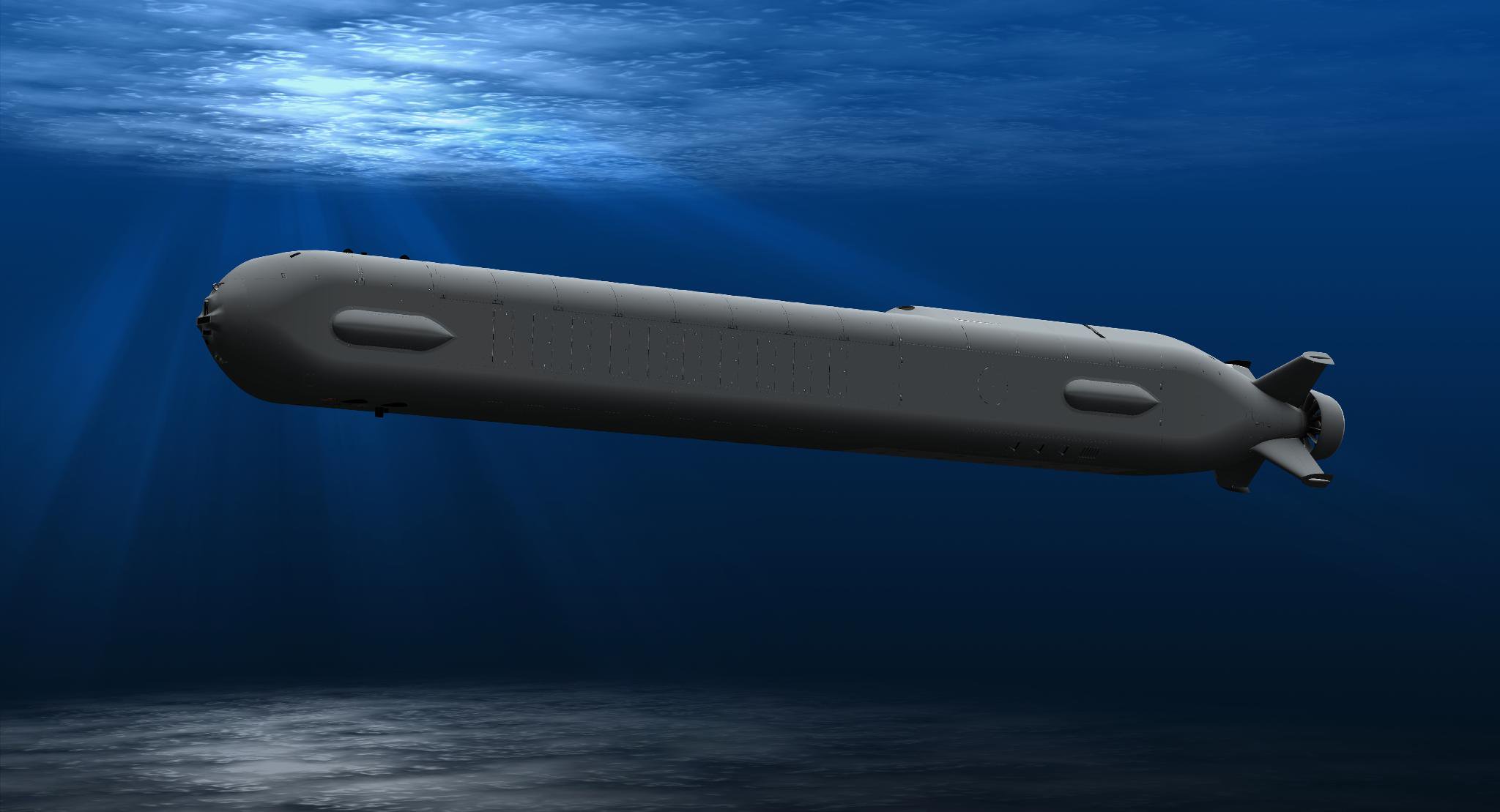

The second key unmanned technology the Marine Corps wants is a long-range unmanned surface vessel, which the service originally wanted for logistics but has since been talked about as a decoy and to launch munitions.

Smith said the service hoped to experiment with five Metal Shark 46-foot commercial boats that would be made semi-autonomous and could carry loitering munitions that, when paired with the Naval Strike Missiles ashore, could put a range of high-value enemy targets at risk.

Third, the service is looking at how to pass data at long ranges and within contested territory. This could be done with the MQ-9 unmanned aerial vehicle, long operated by the Air Force and now being adapted for a maritime mission by the Marines. The Marines already operate two MQ-9A extended range UAVs in the U.S. Central Command area of operations, and the service plans to procure 16 more to create three squadrons of six aircraft each, Smith said. Those UAVs would be operated from bases in the U.S., in Guam or in friendly nations.

“That system is incredibly important to us to pass data across the battlefield; it is the closer of the kill chain, maritime kill chain, as we operate underneath, again, an alternate precision navigation and timing network. That system has the duration and the range to be operated from those bases that we do control and still give us the loiter time that we need to be able to both close the kill chain and to move that asset around something as vast as the Indo-Pacific theater,” Smith said. He later added that the MQ-9 or something like it would be needed to connect the most forward-deployed Marines already inside the enemy’s weapons engagement zone with those flowing in if a fight were to occur.

Though the Navy and Marine Corps leaders expressed clear visions of what they thought operations would look like with unmanned systems collecting intelligence, passing data, jamming enemy networks, laying mines underwater, launching munitions and more, lawmakers wanted to see more on how uniformed and Department of Navy leadership would manage the whole effort: not just developing the platforms, but also developing the networks, the autonomy, the data formats and waveforms, the payloads and more, and fielding them all together in complementary timelines without any major acquisition mistakes that would throw off the whole effort to move to a hybrid force.

“I was really disappointed in what I saw as a lack of substance in the plan; I thought it was full of buzzwords and platitudes but really short on details,” Rep. Elaine Luria (D-Va.) a retired naval officer and the vice chair of the HASC, said during the hearing.

Asked for more details on program management and accountability by USNI News and others earlier in the week during a media roundtable, Kilby had said he didn’t think there was a need to reorganize the Navy to ensure that unmanned systems and their enablers are successfully fielded, but he did acknowledge the need for regular, high-level attention to prevent things from slipping through the cracks. He said he, Smith and Stefany were committed to ensuring the vision of a hybrid fleet becomes reality – but with uniformed and secretariat leaders only in their jobs for limited amounts of time, questions remain about the long-term ability to see with unmanned campaign plan through.

Which is where Rickover comes back in.

Rep. Jack Bergman (R-Mich.), a retired Marine Corps lieutenant general, offered up a solution to the accountability problem:“the nuclear navy is as good as it is because the [subject matter expert] was a guy named Rickover. And when you think about, in creating the nuclear navy, you had a person who led that effort over roughly 60 years in uniform. Now I’m not suggesting that you need someone in uniform for 60 years, but we do need the ability, as political appointees turn over, as admirals and generals turn over, and even subject matter experts usually in the grade of O-4, O-5 probably turn over, that because we have a new program – and if you wanted to call the new program … unmanned – I would suggest that the way we’re going to be long-term successful in the fight, in other words fielding the capabilities necessary, is to create some kind of a long-term accountability for results within the Department of the Navy.”

Bergman suggested going outside the traditional rules for military career paths “to actually create a carve-out, if you will, for a career path for that individual or very small group of individuals who will shepherd unmanned into the warfighting capability that we know we need it to be.”

Kilby explained that the Navy began with a decentralized approach to unmanned systems in the early 2010s and then in 2015 created a Director of Unmanned Systems (OPNAV N99) position and a Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Unmanned Systems to centralize the work across platforms and domains – both of which were abandoned by early 2018, leaving the Navy again with no one in charge of holistically shepherding unmanned technologies into the fleet.

“I think we need another approach which is not to go one way or the other, right full rudder or left full rudder, but to have centralized management of this with decentralized execution at the platform and the domain level, from an air perspective, a surface perspective, and an undersea perspective, understanding there’s going to be cross-pollination across those domains,” Kilby told Bergman.

“So I owe the CNO an answer” about how to address management and accountability, but for the moment, he said, “we haven’t come up with the answer.”