CATANIA, Sicily – The future of anti-submarine warfare for countries who can’t afford to invest in top-of-the-line submarines and maritime patrol aircraft could be a netted fleet of unmanned platforms that can create “passive acoustic barriers” at chokepoints or drag towed arrays through a country’s territorial waters.

NATO’s Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation is showcasing these ideas at NATO exercises such as the ongoing Dynamic Manta annual ASW exercise, showing off novel operations that could one day be commonplace if navies and their industrial bases decide to invest.

CMRE Director Catherine Warner said the organization has been working with autonomous vehicles in the undersea warfare area for the past 20 years to understand how they can contribute to perhaps the most complex type of naval warfare.

“The big idea in this whole realm of unmanned systems is figuring out the right systems with the right sensors and the right scenario that’s going to be cost and operationally effective,” she told USNI News after the kickoff of Dynamic Manta. She said ASW is “high-end asset-intensive” and that, while unmanned vessels can’t do everything a manned sub or plane can, they can perform some specific missions that would be cost-prohibitive to do with manned vehicles.

One prime example is the passive acoustic barrier. Noting that CMRE puts passive sensors on all the autonomous vehicles, buoys and seabed devices the organization puts in the water, Warner said CMRE used all its sensors to demonstrate a passive acoustic barrier off the coast of Sicily in the days leading up to the start of Dynamic Manta.

While in this demonstration they tracked the flow of commercial ships across the “barrier,” the ultimate idea would be to track the movement of submarines at chokepoints such as the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap. The specifics of the unmanned vehicle wouldn’t matter as much as the quality of the sensor and the ability to differentiate the clutter from the sounds of submarines.

On the more active side of sub-hunting, CMRE has been particularly focused on the idea of multi-nation multistatic ASW, where an active sonar source would create pings for dozens or hundreds of passive sensors listening for those sound waves to bounce off of enemy submarines. The more sensors that are in the water, the better they can detect pings and recognize what kind of submarine is moving through the water and in what direction.

During Dynamic Manta, CMRE operated alongside manned warships to join in the hunt for submarines, using its “network”: NATO research vessel NRV Alliance, two Ocean Explorer 21-inch diameter autonomous underwater vehicles named Harpo and Groucho, and a fleet of Liquid Robotics’ Wave Gliders that serve as communication nodes between the ship and the AUVs. Harpo and Groucho have a towed array to listen for pings, and more recently CMRE developed a towed array for the Wave Gliders as well to put more ears in the water.

“Having that extra set of sensors makes a huge difference” in multistatic ASW, Warner said, because when an active sonar source like the variable depth sonar on Alliance or a warship like Italian frigate ITS Carabiniere (F 581) sends out energy, they want as many passive sensors in the water as possible to listen for pings.

“When you do multistatic, there’s so many more advantages because of the geometry and the extra chances for reflections. So we can do it with ourselves, but if we could do it with all the nations – and that is something that we strive to do with our interaction with the nations … – then everybody, wherever they are, that has a sensor, being able to know the sound source and sync to it and coordinate on the reflections – it is very power to be able to do that.”

The key to multi-nation multistatic ASW is information-sharing: they’d all have to know where exactly the active sonar source is, so they could correctly calculate what the pings they pick up mean, and then they’d have to share what they’re hearing with all the other nations involved, too, so they could all adjust their positions as needed to get the best chance at hearing the target submarine and help track it through the water.

Information-sharing can be a hurdle with something as sensitive as ASW, with nations often not wanting others to know the exact nature of their capabilities, but Warner said the scale to which NATO could track submarines under the water would be powerful if everyone could find a way to come together.

Today, Harpo and Groucho talk to each other while looking for subs, and if one picks up a sound they will coordinate amongst themselves to get into the best positions for the best geometries to hear sonar pings. The more AUVS in the water collaborating, the better.

“We’ve done it. We’ve already shown that multistatic ASW works. That’s our system: we’ve been doing it since 2012 in Dynamic Manta, we’ve demonstrated it operationally, and we just keep adding things onto it. So it can be done. So, whether other nations want to do it with us, that’s up to them,” Warner said.

Warner said Harpo and Groucho are 21-inch diameter AUVs that were built by Florida Atlantic University. The vehicles themselves are 18 years old, but the batteries and sensors are constantly being upgraded, meaning the vehicle that originally had four hours of battery life can now operate for 72 hours without intervention.

CMRE’s Dan Hutt told USNI News that the next step would be to scale up these operations. To conduct multistatic ASW in the GIUK Gap, for example, would require hundreds of AUVs from participating NATO nations. The idea, though, would be to “flood the ocean with lots of cheap assets – they all have sensors, potentially different kinds of sensors, they can all talk to each other over a vast network – that’s a really powerful concept for ASW. We only have a handful of these, so we want to scale up and work with the nations to do a bigger demonstration.”

While several NATO countries are upgrading their fleets of “high-end submarines and frigates,” many cannot afford such exquisite systems, Warner said.

“But they certainly can afford a fleet of unmanned vehicles with towed arrays. And if they were all using the same standard, they could all buy from their own countries’ industry – that’s what we’re about, we’re not competing with industry, we’re developing standards,” she continued.

“Every nation’s industry would benefit from building these vehicles and the towed arrays, and then they could all operate together.”

CMRE has already done a machine learning effort to support the back end of this effort – researchers collected 52 days worth of sonar echoes from diesel-electric submarines (SSKs) and created algorithms to help the unmanned vehicles recognize SSK sounds and ignore the clutter. This could be shared with the NATO members who want to join in this effort. Warner said Norway, Belgium and the Netherlands are taking steps to incorporate AUVs into their ASW efforts, but she’s hoping to see more.

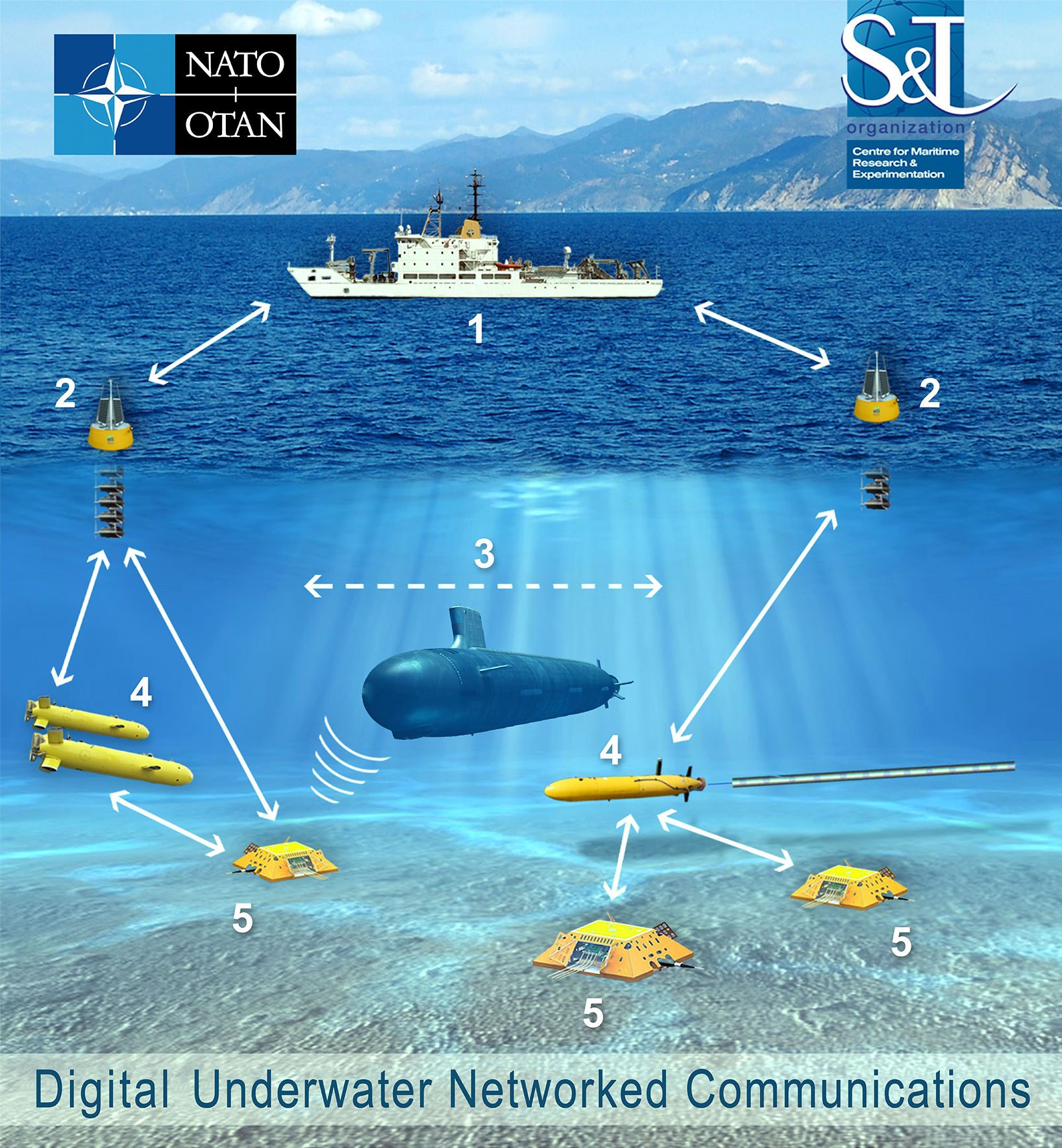

A final technology CMRE is showing off at Dynamic Manta is an undersea communication network. NATO nations had previously agreed to use the JANUS as the digital underwater communications standard, but CMRE is still hard at work developing waveforms that will be cyber-secure and low-probability of intercept, as well as developing concepts of operations for its usage.

Ahead of Dynamic Manta, CMRE demonstrated they could use JANUS to send submarines the surface picture with Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracks – so the submarines could know how to safely surface – by sending the message from a ship, through the Wave Gliders as comms nodes, and to the submarine underwater.

Warner said they call this setup “WetsApp” – a nod to the WhatsApp digital communication app on cellphones – and said it’s a vast improvement over the voice communication tools they previously used to send messages to submarines, which could easily get garbled or lost altogether.

“Before, when they were submerged, submarines could only use something called an underwater telephone, which is very difficult to use, it’s distorted, hard to understand,” she said.

“But we can actually text them – we have a little program, we call it WetsApp, sort of WhatsApp, and we can send them for example the surface picture – if they were going to come to the surface, they would know where all the ships are on the surface. So that’s very important technology that we’ve already helped insert into the industrial base.”