ABOARD ITS CARABINIERE, IN THE IONIAN SEA – All across the Mediterranean Sea, more non-NATO countries are fielding submarines while NATO allies are increasing the size of their own undersea fleets. Those submarines are also becoming harder to find.

All told, the ability for NATO to find, track and identify submarines is not just a matter of defense against Russia, but a matter of basic traffic safety on and under the Mediterranean.

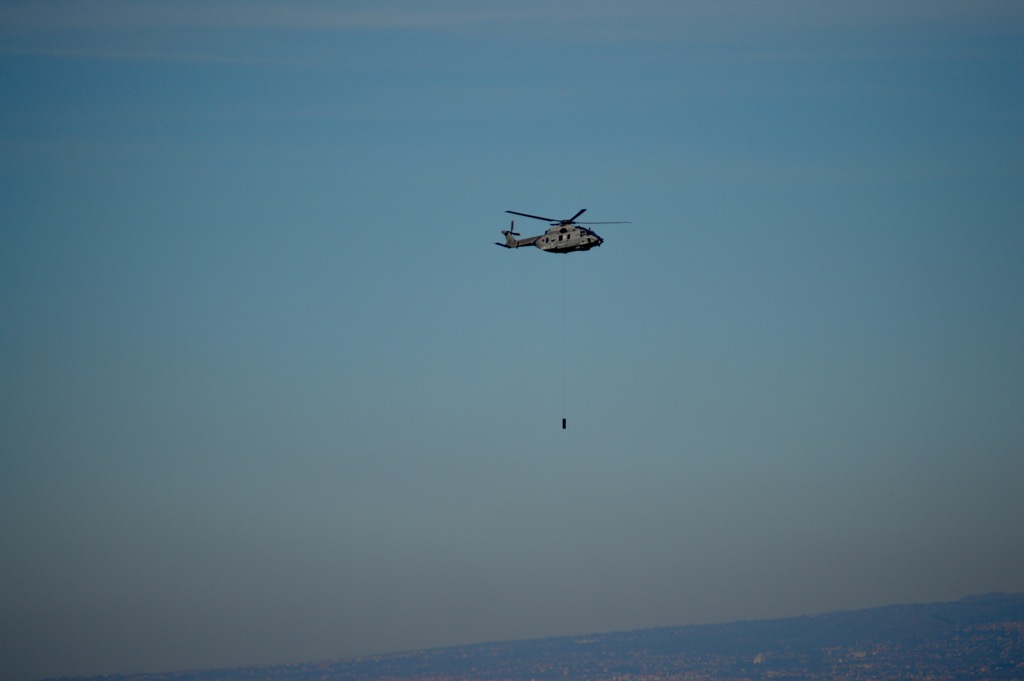

Set against the backdrop of the increasingly crowded Med, NATO is hosting the Dynamic Manta 2020 anti-submarine warfare exercise, bringing together nine nations to combine ASW capabilities from ships, maritime patrol aircraft, helicopters and submarines, and improve their ability to work together to keep these southern European waters safe.

Dynamic Manta was designed “to train, to prepare, to test our ability in a very particular domain, that is the anti-submarine warfare,” Italian Navy Rear Admiral Paolo Fantoni, who commands Standing NATO Maritime Group 2, said ahead of the kickoff of the exercise.

“All this to facilitate the integration of forces. That is the goal and the strength of NATO: the capability for the alliance to operate with different forces from different nations using the same standards and procedures, and to be able to react properly to any type of emergency.”

SNMG-2 commands the surface forces in the exercises and is one of four very high readiness surface forces that NATO maintains under its Maritime Command (MARCOM).

Fantoni told USNI News during an interview aboard SNMG-2 flagship ITS Carabiniere (F 593) that ASW is tough enough for one nation to do, but combining ships and aircraft from multiple countries is a challenge. Each bring different kinds of sensors onboard ships and aircraft of different ages and sophistication. For example, under his command is Italian frigate Carabiniere, an ASW-variant FREMM frigate that delivered to the fleet in 2015. Also in the task group is Hellenic Navy frigate HS Aegean (F 460), which was commissioned into the Royal Netherlands Navy in 1980, sold to Greece in 1993 and modernized in 2010. Fantoni said all the ships are trained to certain NATO standards before they are assigned to a NATO group like SNMG-2, but his job is to figure out how to make the most of the differing capabilities each ship brings.

“We need to operate as a force – not Carabiniere acting on her own and (Canadian frigate) Fredericton and the others on their own – the ships are a part of the scenario for the interactions: they have to achieve some goals, to detect the submarines, to take some actions against the submarines, and vice versa to defend themselves, to defend a nearby unit from a submarine attack,” he said, calling it a “force-multiplier” when they can share information and hunt a sub collectively rather than operating in proximity but independently.

Everyone involved in the exercise can perform some ASW, but some assets bring especially advanced capabilities: Carabiniere has a variable-depth sonar, some helos have a dipping sonar to supplement their airborne sensors, the fixed-wing planes have great endurance and range.

“It’s like an orchestra. I feel like, really, a director of an orchestra to use different instruments as much as they can contribute to my mission,” Fantoni said.

In the complex undersea environment in the Mediterranean, squeezing out the most capability from SNMG-2 and the ships and aircraft it partners with during exercises like Dynamic Manta is key.

“This August, Russia did Exercise Ocean Shield, which was the largest post end of the Cold War exercise conducted by Russia. And one of the components of [NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe]’s guidance is that we conduct deterrence and defense of the Euro-Atlantic Area. The point of Dynamic Manta is to show a credible defense, that we have the ability to act interoperably within the ASW realm,” Rear Adm. Andy Burcher, commander of NATO submarines at MARCOM, said during a press conference aboard Carabiniere on Feb. 24 the first day of the exercise.

“In addition to that, I would say that all of the large number of nations that surround the Mediterranean are increasing the number of submarines that are operating in the Mediterranean: Algeria, Egypt, Russia and Israel are now all operating submarines in the Mediterranean. And a large number of our NATO alliance countries are increasing their submarine footprint in the area: Spain, Italy, Turkey, I believe Greece, are all conducting expansion programs within the submarine realm. So from a submarine perspective, the number of submarines that are operating in the Mediterranean is increasing, so it’s important that we understand how the Mediterranean operates, and in particular, all of these submarines that are coming in have advanced capabilities in comparison to the past. So we have to stay both proficient and capable in the ASW realm. So those are the factors that I see in the Mediterranean that make this exercise important.”

On Russia specifically, Fantoni said that, “they are military vessels, they don’t belong to the alliance, they are present – so we could consider them as a threat, but I don’t see a threat, an immediate threat to the forces. We respect their potential capability but also confident that we are as well prepared for any type of emergency.”

Maintaining a Fight-Tonight Force

If the purpose of NATO’s four standing maritime groups is to ensure there’s always a task group integrated and ready to respond to an emergency, the purpose of exercises like Dynamic Manta and its sister exercise in the North Atlantic, Dynamic Mongoose, is to allow those task groups to prove their proficiency in specialized warfare areas.

Burcher said during the press conference that, if a war were to break out, NATO countries could bring a great number of submarines to the fight: 12 NATO countries have a combined 69 submarines, and though the U.S. Navy typically doesn’t lend its submarines to NATO for tasking, it could bring about 30 Atlantic-based subs to the fight if the need arose. Those 100 subs, plus the frigates and destroyers and helicopters and maritime patrol aircraft that would supplement them in a hypothetical fight against the Russian submarine fleet, are all capable assets – but integration only comes through practice. By rotating which nations are involved in the standing groups and which participate in exercises like Dynamic Manta, all nations are exposed to some amount of integrated theater ASW operations through NATO and are able to develop some sort of institutional knowledge.

In Dynamic Manta 2020, a series of CASEXs increase in complexity, from familiarization efforts up through a graduating event of coordinated theater ASW with air, surface and subsurface assets contributing to finding an enemy submarine, Burcher explained. Early on, a ship might be told that the target is in its operating box and be given its course and speed to see if it can positively find and identify the submarine with its systems; by the end, the ship might be told a target is within its operating box but it won’t have any clues as to its location or course.

Four submarines are participating, with subs serving as targets as well as ASW assets. Nine countries total are involved, as well as NATO’s Center for Maritime Research and Experimentation, which is bringing unmanned undersea vehicles and gliders to contribute to sub-hunting operations while also testing out the new gear and new tactics, which Burcher said “brings in an extra added tool to the undersea fight.”

Fantoni said MARCOM is constantly identifying gaps, noting lessons learned, testing out new concepts to fix those gaps, and then ultimately updating doctrine so NATO forces will train to the best and most relevant capabilities. Much of this is driven by ever-changing capabilities both in NATO assets as well as potential target submarines.

“Technology is evolving very very quick, and of course we adapt our doctrine to the new capabilities. One basic example: if in the past your sensors were able to detect a submarine at 10 kilometers, and now your sensor allows you to detect beyond that limit, you need to adjust to how you intend to use the tactics that goes behind it,” Fantoni told USNI News.

“But also the submarines are getting new technology, so we change on a yearly basis” from exercise to exercise.

Dynamic Manta takes place in the Ionian Sea, in the Central Mediterranean in waters with relatively less commercial shipping traffic. Dynamic Mongoose takes place in Northern Europe, typically rotating between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean to allow northern NATO navies to practice in shallower waters and in the deep ocean.

Fantoni called Dynamic Manta and Mongoose two of “the most interesting and viable activities and represent today the highest level of integration of forces in anti-submarine warfare. Very beneficial to surface vessels, for maritime patrol aircraft, and indeed for the submarines.”

“Submarines are constantly improving their stealth, their quietness. They are improving in their tactics and the sensors that they have, and so these types of exercises allow us to really put theory to practice and make sure that we understand what we’re doing in a highly complex environment,” Burcher said.

“Because anti-submarine warfare requires both air, surface and submarine assets to detect the other submarines, it’s important that we learn how to and we practice in a combined environment.”