China is not only a pacing threat to the U.S. naval fleet but also to the American shipbuilding industry and supply chain, Navy leaders and lawmakers said today during a Senate Armed Services seapower subcommittee hearing.

Navy acquisition chief James Geurts said during the hearing that “our pacing threat from China is their ability to scale and produce, leveraging their very strong marketplace.” The U.S. needed to bolster its own shipbuilding industrial base, too, to remain competitive and healthy enough to scale up as the Navy tries to grow its capacity to compete with China.

Lawmakers in the House and Senate worried the Navy was shooting itself in the foot in that respect, introducing instability to the shipbuilding industry at the very time the Navy should be strengthening it.

In a later hearing with the House Armed Services’ seapower and projection forces subcommittee, Geurts said the U.S. shipbuilding base and supply chain was in place today to get to 355 ships by 2030, but the money isn’t there to buy these ships and scale the fleet up alongside China’s.

Several congressmen on the committee took issue with this description of the industrial base, though, saying that the Navy is creating instability for industry by drastically changing its long-range plans from year to year. On the submarine side, previous long-range plans called for continued two-a-year production of Virginia-class submarines to keep industry stable as it tries to add in the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine work too, but this year the FY 2021 budget request unexpectedly cut the second SSN to divert more funds to the National Nuclear Security Administration. And money in this current fiscal year meant to keep amphibious warship construction moving along smoothly has been redirected to pay for border wall construction. In both these cases, the decision to take money from shipbuilding programs was made at the Pentagon or administration level, not by the Navy.

“What we’re doing to our industrial base and our suppliers – and there’s no better example than with the Virginia-class submarine and delaying the submarine – is the fact that they want to invest, they want to build the ships, they want to hire and train the workforce, but we keep changing the plan,” Rep. Elaine Luria (D-Va.) said during the HASC hearing.

“And last year at these hearings I brought up the 30-year shipbuilding plan as an example. If the 30-year shipbuilding plan changes every single year in years one through three – not the end of it, 20 to 30 years from now when we could expect there’s change, but if it changes the immediate plan every year, how is it a plan? How can the industrial base plan for that?”

Despite the noticeable changes to the plan at the shipbuilder level, Geurts said his office was tracking industrial base health closely at the supplier level and looking for specific areas in need of support.

“I have hired a full-time supply chain expert, and we have created a whole supply chain set of expertise across all of our programs,” he said. China is, “also competing with us and against us in many of the supply chain areas, so supply chain integrity, really understanding that supply chain, what it costs, where we have fragility, where we have opportunity, is a critical thing we’ve really been focused on for the last two years or so. We’re starting to see that really add benefit.”

He said his office is paying particular attention to the nuclear shipbuilding industry, which builds components for the Ford-class aircraft carrier as well as the Virginia attack boats and the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine.

Geurts said the carrier construction and refueling business at Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Industries employs about 10,000 people at the Virginia yard, but it also relies on 50,000 people at 2,000 suppliers in 46 states. A range of factors – including Chinese companies buying American suppliers – has contributed to fragility in the supply chain in some areas, with perhaps just one supplier who may not be able to keep up with the increasing nuclear shipbuilding workload or who may be especially sensitive to cuts in the budget, such as the second Virginia being taken out of the 2021 request.

Despite Geurts’ praise for the current health of the shipbuilding industry and his office’s attention to the health of the supply base, SASC seapower subcommittee chairman Sen. David Perdue (R-Ga.) said both aspects of this competition with China – the naval force and the industrial base – are being hurt by the Fiscal Year 2021 budget request, which cuts 10 ships from Navy construction plans over the next five years and hurts both industry and the fleet’s ability to grow as fast as needed.

“It appears to me that the Department of the Navy’s proposed budget is sufficient to support a fleet of about 300 ships. The budget proposal for fiscal years 2021 through 2025 does not keep pace with inflation, which means growing the Navy much at all, much less to the 355 ships we need to meet all the threats we face, is financially unrealistic,” Perdue said in his opening statement.

“I think it is time we rethink how we fund our Navy and shipbuilding enterprise. Today, we spend roughly $750 billion on our military. Each department of the military gets roughly one-third of what’s left after overhead. Our current National Defense Strategy is a maritime strategy, as former Secretary Mattis stated. I am skeptical that the current one-third funding level for the Department of the Navy is enough to meet that goal. If we are to remain the global leader above, on, and under the seas, we must get serious about building the fleet we need.”

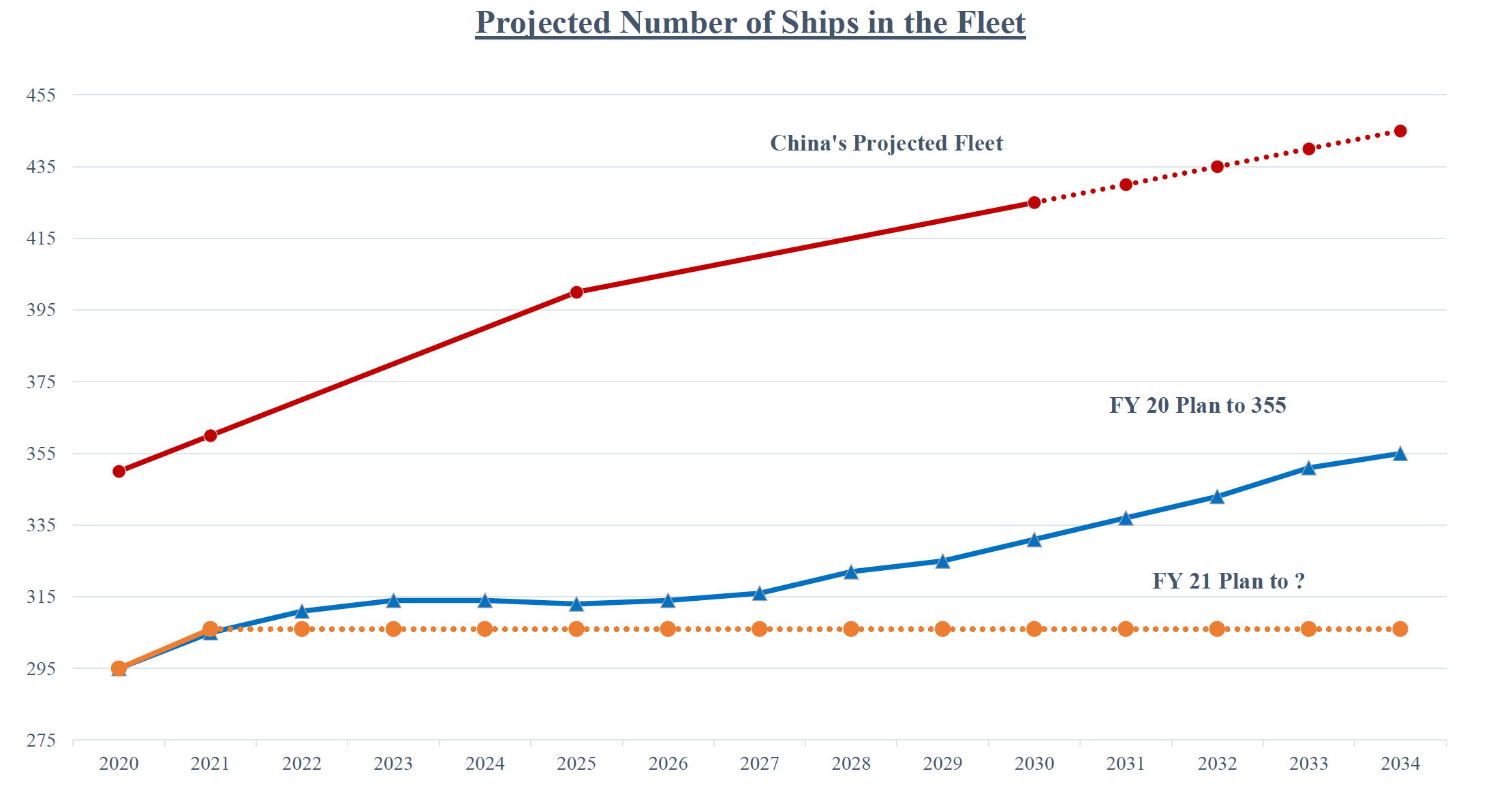

Perdue went on to show a chart comparing China’s naval buildup compared to the U.S. Navy’s. The chart shows China surpassing 355 ships this year and reaching 425 by the end of the decade, in 2030. The U.S., on the other hand, has 296 today and hits 331 by the end of the decade. The U.S. Navy would reach 355 ships by 2034 under the FY 2020 budget request. An updated ship inventory projection based on cutbacks in shipbuilding and accelerated decommissionings of some ships proposed in the FY 2021 request hasn’t been made available yet due to the Pentagon delaying its release to run additional analysis.

“This year, there is no shipbuilding plan and the budget documents reflect a fleet size of about 306 ships. I would observe shipbuilding and fleet size trends, and therefore the Navy to some extent, seem to be going in reverse in this budget request, as compared to the Department’s previous plans,” he said.

“We are also hearing about ‘affordability’ and the ‘best balance of resources’ in hearings this year. I applaud the effort to adequately fund personnel, maintenance and other supporting functions. However, we cannot lose sight of the fact that the Navy must get bigger and we must find a way to pay for it. Because if we don’t, make no mistake, the Chinese will only accelerate the expansion of their maritime influence around the globe, creating fait accompli dilemmas at every turn, which come at the expense of U.S. interests and those of our partners and allies. The stakes are real.”