WASHINGTON, D.C. – Escort carrier USS St. Lo (CVE-63) was the first naval vessel to be sunk by a single precision-guided weapon, a Japanese kamikaze attack, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Since then the danger to surface warships today has “only gotten worse,” the former vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs said on Friday.

The 1944 clash off the coast of the Philippines was the “culminating naval battle” in the Pacific of World War II and taught the U.S. lessons that have endured in the modern naval era, said retired Adm. James “Sandy” Winnefeld speaking at the Decatur-Truxtun House. Along with the introduction of precision-guided weapons into naval warfare, the battle also reasserted how naval battles have influenced American ground conflict since the Revolutionary War.

The naval victory at Leyte Gulf allowed Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s invasion of the Philippines to succeed as much as the French navy’s success set up the 1781 victory at Yorktown by cutting off British troops from evacuation or resupply, Winnefeld said during a discussion on the 75th anniversary of the battle.

Even though MacArthur’s landings had begun before the naval engagement, not all of the American forces and equipment were ashore; and although protected by naval screens, the transports and other auxiliaries were at risk from the Japanese.

“The Navy did its job and protected the Army force that landed,” the Naval Institute’s Thomas Cutler said during another part of the program.

Another lesson from Leyte Gulf that has carried forward “was the disproportionate effect of submarines” on the battle’s outcome and the role they play today in naval combat, he said. After the first day, when three heavy cruisers were sunk or heavily damaged, “Japanese commanders ignored their presence at their peril.”

Another important lesson learned in the night battles in Leyte Gulf was the value of torpedoes fired from surface ships, said Cutler, author of the Naval Institute Press’ Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23-26 October 1944 and editor of Leyte Gulf at 75. Because there were no gun flashes smaller American destroyers, destroyer escorts and even PT boats could successfully attack larger Japanese ships, he said. The effect of technical sophistication of the more advanced American fire control radar also proved lethal, he said.

Perhaps more than the technological dimension, the battle highlighted the essential value of unity of command, several panelists said. The naval forces of Adm. William “Bull” Halsey and Vice. Adm. Thomas Kinkaid had two separate chains of command that led to unnecessary confusion during the naval battle, a panel agreed.

The split in command between two fleets converging on the same location, not communicating or coordinating much with each other, became obvious when Halsey ordered all of his ships in the 3rd Fleet to steam north in pursuit of what turned out to be a decoy force.

Vice Adm. Thomas Kincaid’s 7th Fleet, under the overall command of MacArthur, remained in place supporting the still unfolding landings and placed this part of the operation at greater risk.

The situation on the Japanese side was not any better, Cutler said. “There’s is no coordination” taking place during the battle and there is no agreement over who is the senior on-scene commander, he said

The battle also provided another lesson for today — being prepared to act quickly when circumstances change.

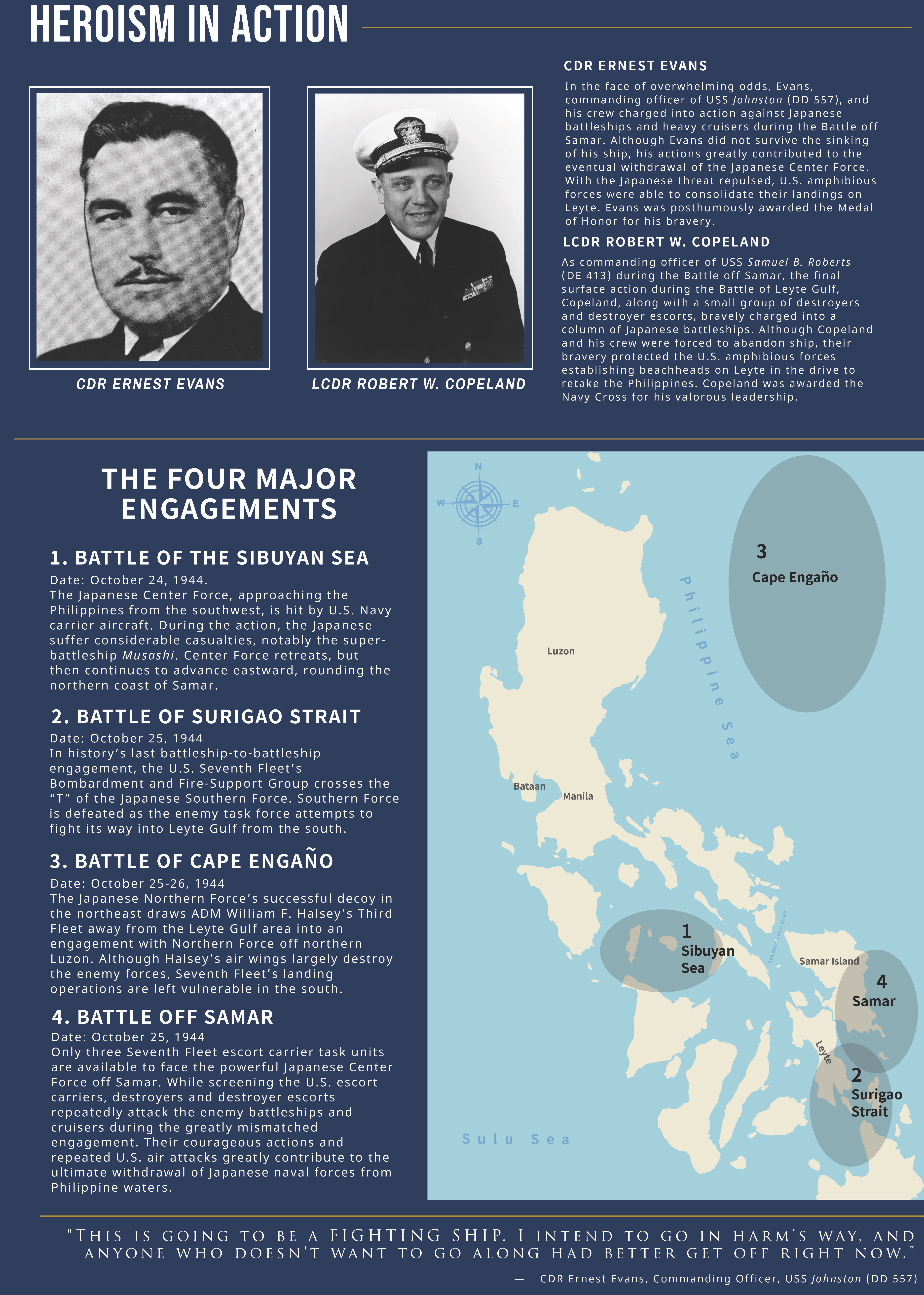

That “ready to go” lesson is often personified in the actions of Cmdr. Ernest Evans at Samar.

“The essence of naval leadership was Ernest Evans,” said retired Capt. David Kennedy, screenplay writer for the film Taffy 3, based on the Battle at Samar. Evans, a Naval Academy graduate, was the commander of the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Johnston (DD-557) in the task force “back with the gear.” Evans “very systematically built a team” that was capable of moving to action even when “they’re not expected to fight,” Kennedy said. Evans’ approach to building a team was apparent when “they attacked with ferocity” against formidable Japanese odds. Evans was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Naval aviation also showed resilience and adaptability at Samar, Cutler said. When the air units assigned to the escort carriers that were tasked to support the U.S. landing saw the Japanese coming, despite not having the proper ordnance, they “continued to attack,” dropping depth charges on the surface ships to disrupt their movement.

During the extended battle, Jack C. Taylor, piloting an F6F Hellcat, and other members of VF-15, “went down on [super battleship Musahi] strafing away” and “managed to pull out just above the water” as they completed the run, his son Andrew Taylor said during the presentation. Taylor and the aviators quickly learned “they had to do it again” to clear the way for the torpedo bombers that were coming in, so they came around for the new strafing attack. The actions from Taylor and the other Hellcat pilots led to the sinking of the Japanese battleship.

The surprising thing to many observers now, Winnefeld added, the sailors “didn’t see themselves as heroes” for what they did at Leyte Gulf.

For the Navy of the future, Winnefeld said, “People like this are our single most important advantage.”