THE PENTAGON – Over the past two years, the number of active duty sailors who committed suicide grew rapidly at a time the overall number of active duty service members taking their lives increased more modestly, according to data from the Department of Defense obtained by USNI News.

The sudden death of U.S. 5th Fleet Commander Vice Adm. Scott Stearney in what is an apparent suicide is part of a troubling trend for the service. During 2017 and the first half of this year, the Navy reported an increase in the number of sailors taking their own lives, and service officials haven’t been able to pin down a cause for the increase.

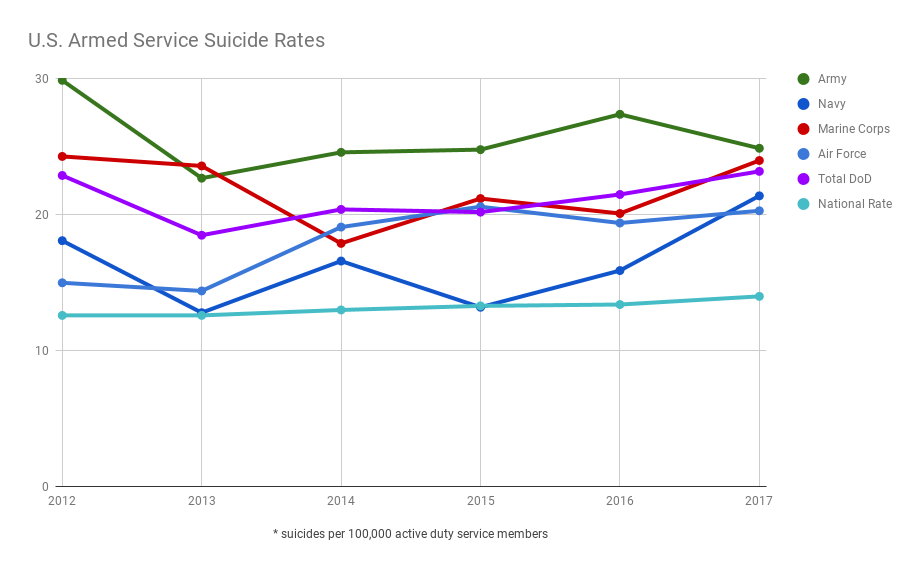

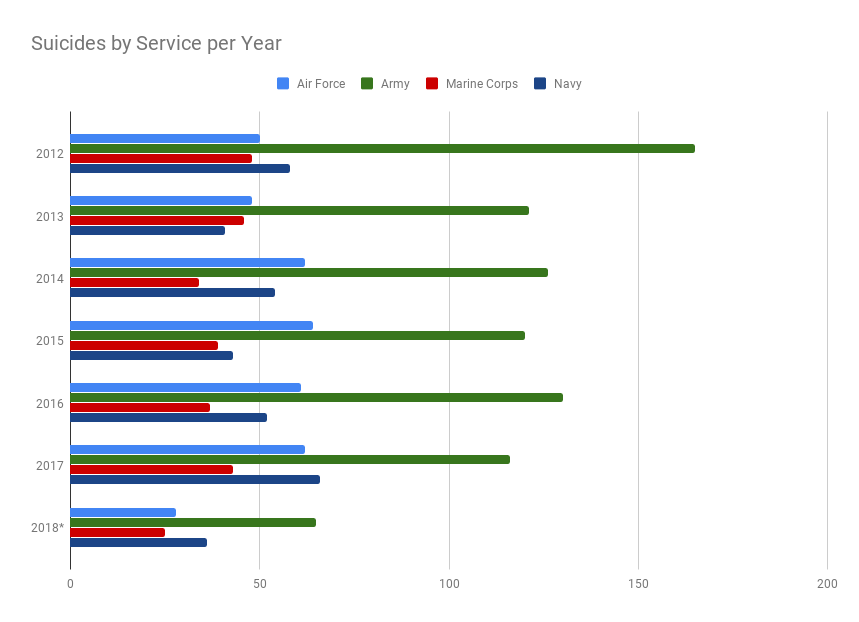

Between 2012 – when the DoD’s Defense Suicide Prevention Office started publishing suicide data – and 2016, the Navy’s suicide rates tracked below the DoD average rate and generally mirrored DoD’s year-to-year ups and downs. In 2017, though, the Navy saw 66 active duty sailors – a 53 percent spike compared to the year before – commit suicide, according to statistics collected by the Defense Suicide Prevention Office. During the first half of 2018, 36 active-duty sailors committed suicides, according to the most recent numbers provided to USNI News. The six-month total suggests the Navy is on track to finish 2018 with a number of suicides similar to 2017’s six-year high.

When compared to other services, the Navy’s 2017 active duty suicide rate of 21.4 per 100,000 sailors was in line with the suicide rates experienced by the other military branches (Army 24.9, Air Force 20.3, Marine Corps 24), according to USNI News calculations using the DoD suicide rate calculation formula. Nationally, the 2017 suicide rate was 14 per 100,000 U.S. residents, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention calculation.

However, before 2017, the Navy’s recent suicide rates had been lower than the DoD rates, even matching the much lower rates for the U.S. general population. In 2016, the Navy’s active duty suicide rate was 15.9 per 100,000 sailors, compared to a DoD active duty rate of 21.1 per 100,000 active duty service members and a national rate of 13.4 suicides per 100,000 Americans. The Navy’s 2015, 2014, 2013, and 2012 rates were also lower than the DoD rates. In 2013 and 2015, the Navy’s active duty suicide rates were essentially the same as the national general public rates of 12.6 and 13.3 per 100,000, respectively.

The Navy isn’t sure why more sailors are taking their own lives. In terms of a longer-term trend, because the publicly available data only goes back to 2012, it’s not clear how the recent rates and the 2015-2017 spike fit into larger historical trends.

“The Navy’s suicide rate has fluctuated over the years, with no single cause for the fluctuations. Nor is there a single theory or study to address fluctuation in any specific year or time frame,” Capt. Tara Smith, a subject matter expert assigned to Navy’s Suicide Prevention Branch (OPNAV N171), told USNI News in an email.

What is known, Smith added, is the suicide rates among the youth and middle age adults have been steadily rising throughout the U.S., according to statistics collected in a 2018 study by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The Navy has identified contributing factors, such as strained and failing relationships, career loss and legal problems, and unreported and untreated mental illness.

Nationally, 44,173 Americans took their lives in 2017, a 7-percent increase from the 44,193 suicides reported in 2015, according to CDC statistics. DoD reported 287 active duty military suicides 2017, an 8-percent increase from 2015 when DoD reported 266 active duty suicides.

Addressing the Problem

Navy leadership responded to the current trend by completely overhauling its suicide prevention policy, releasing OPNAV Instruction 1720.4B in September, Smith told USNI News.

“The Navy has been actively addressing the interpersonal problems of suicide through our updated policies, programs and training,” Smith said. “The new Suicide Prevention Instruction, OPNAVINST 1720.4B, strengthens suicide prevention training and targets lethal means access, building healthy relationships and connectedness, and reducing barriers to help-seeking.”

Identifying individuals who are at risk of taking their lives, though, can present a challenge for the military.

“Researchers found that more than half of people who died by suicide did not have a known diagnosed mental health condition at the time of death,” the 2018 CDC study states. “Relationship problems or loss; substance misuse; physical health problems; and job, money, legal or housing stress often contributed to risk for suicide. Firearms were the most common method of suicide used by those with and without a known diagnosed mental health condition.”

The Navy’s revamped suicide prevention program focuses on creating a system for commands to identify and provide treatment to at-risk sailors before they attempt suicide. All members of the Navy, both active duty and reservists, are to attend suicide prevention training. Commands are to have suicide prevention program managers to help guide individuals considered to be at risk to mental health treatment.

“Our Every Sailor, Every Day campaign is designed to educate and empower sailors to practice ongoing self-care, as well as lethal means safety during times of increased stress,” Smith said, referring to the Navy suicide prevention program. “It also encourages seeking help by sharing real-life experiences of sailors who have reached out, completed treatment and thrived in their careers, as well as policy-related facts that dispel misperceptions about negative career impacts.”

The Navy’s leadership also wants to create an environment where all active duty personnel balance their work and personal lives. Earlier in the fall, Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran told all flag officers they were required to take ten consecutive days of leave each year.

Moran issued the verbal command to take vacations because of a concern too many of the Navy’s leaders were at risk of burning-out, Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Adm. Robert Burke said during the recent Naval Submarine League annual symposium. The Navy hopes enlisted and officers will follow the flag officer examples and also take leave.

“Preventing suicide in the Navy is an all-hands responsibility. Each life lost is one too many,” the new guidance signed by Burke says.

Not the First Time

Professional success often masks underlying mental health issues, said Keita Franklin, the national suicide prevention in the Veterans Administration’s Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Franklin spoke about suicide among veterans recently at a Brookings Institute panel discussion focused on veteran’s health issues.

“This is not an E-1 to E-4 issue. It’s a multi-generational issue,” Franklin said.

As examples, Franklin cited the suicides of Kate Spade, the founder and former owner of the Kate Spade brand, and Anthony Bourdain, the celebrity chef, author, and television culinary documentarian. Both Spade and Bourdain were very successful people who ended their lives in 2018.

In May 1996, shortly before a scheduled interview with a reporter from Newsweek, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jeremy Boorda shot himself in the chest at his home at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C.

The suicide of the Navy’s top officer caught the entire military community by surprise. An ensuing investigation by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service made no conclusions about why he killed himself.

However, at the time Boorda took his life, the Navy was facing several challenges, according to media accounts. The Navy was contending with the fall-out from the 1991 assault of dozens of women at the annual Tailhook convention of naval aviators, sexual assault allegations faced by several senior naval officers, a cheating and drug use scandal at the U.S. Naval Academy, and questions about the training and maintenance of F-14 Tomcats after several crashes. The Navy did not release two notes left by Boorda.

The Navy’s new suicide prevention guidance acknowledges warning signs might not be apparent and too often sailors in times of personal crisis do not realize there is help available. The policy seeks to establish a culture where commands reach out to individuals, and sailors experiencing a personal crisis know help is available.

“Each life lost is one too many. Navy policy, consistent with Department of Defense policy, requires leaders to foster command climates that promote health and a sense of community, remove barriers to seeking help, increase awareness of resources, and take appropriate action when a sailor is in need,” the policy states.

Suicide Prevention Resources

The Navy Suicide Prevention Handbook is a guide designed to be a reference for policy requirements, program guidance, and educational tools for commands. The handbook is organized to support fundamental command Suicide Prevention Program efforts in Training, Intervention, Response, and Reporting.

The 1 Small ACT Toolkit helps sailors foster a command climate that supports psychological health. The toolkit includes suggestions for assisting sailors in staying mission ready, recognizing warning signs of increased suicide risk in oneself or others, and taking action to promote safety.

The Lifelink Monthly Newsletter provides recommendations for sailors and families, including how to help survivors of suicide loss and to practice self-care.

The Navy Operational Stress Control Blog “NavStress” provides sailors with content promoting stress navigation and suicide prevention:

NavStress social media:

Facebook: www.facebook.com/navstress

Twitter: www.twitter.com/navstress

Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/navstress