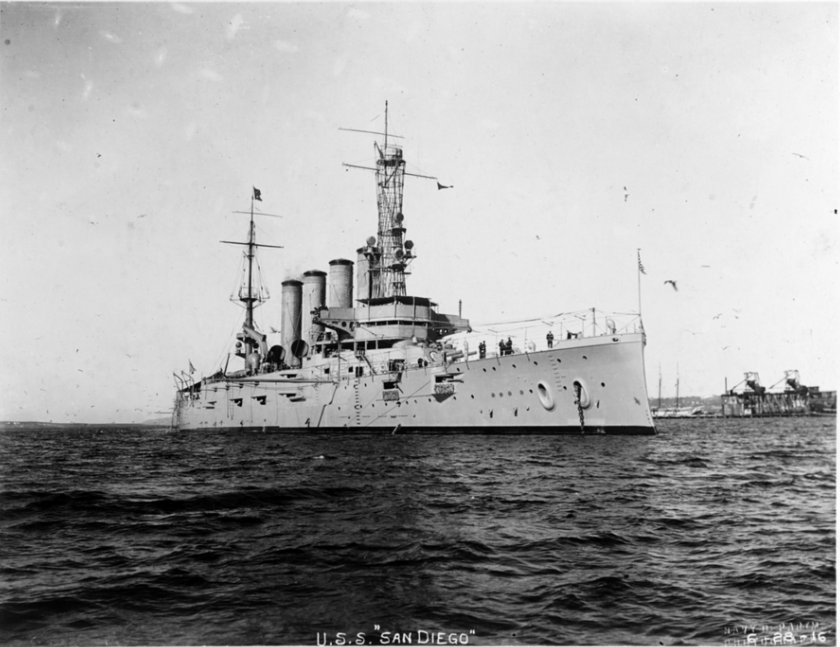

Steaming to New York with a belly full of coal, the armored cruiser USS San Diego (ACR-6) struck a mine deployed by a German U-boat on July 19, 1918.

The mine exploded along the cruiser’s aft port side, near compartments filled with coal and one of the ship’s four tall stacks. Within 25 minutes, despite initial efforts by the crew to keep the ship steaming ahead as water rushed into its spaces, San Diego continued to list until it sunk in shallow water.

Those findings, presented Tuesday at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in Washington, D.C, validated earlier determinations including a Navy court of inquiry that San Diego was sunk by a mine deployed by U-156 and not by a torpedo or a saboteur.

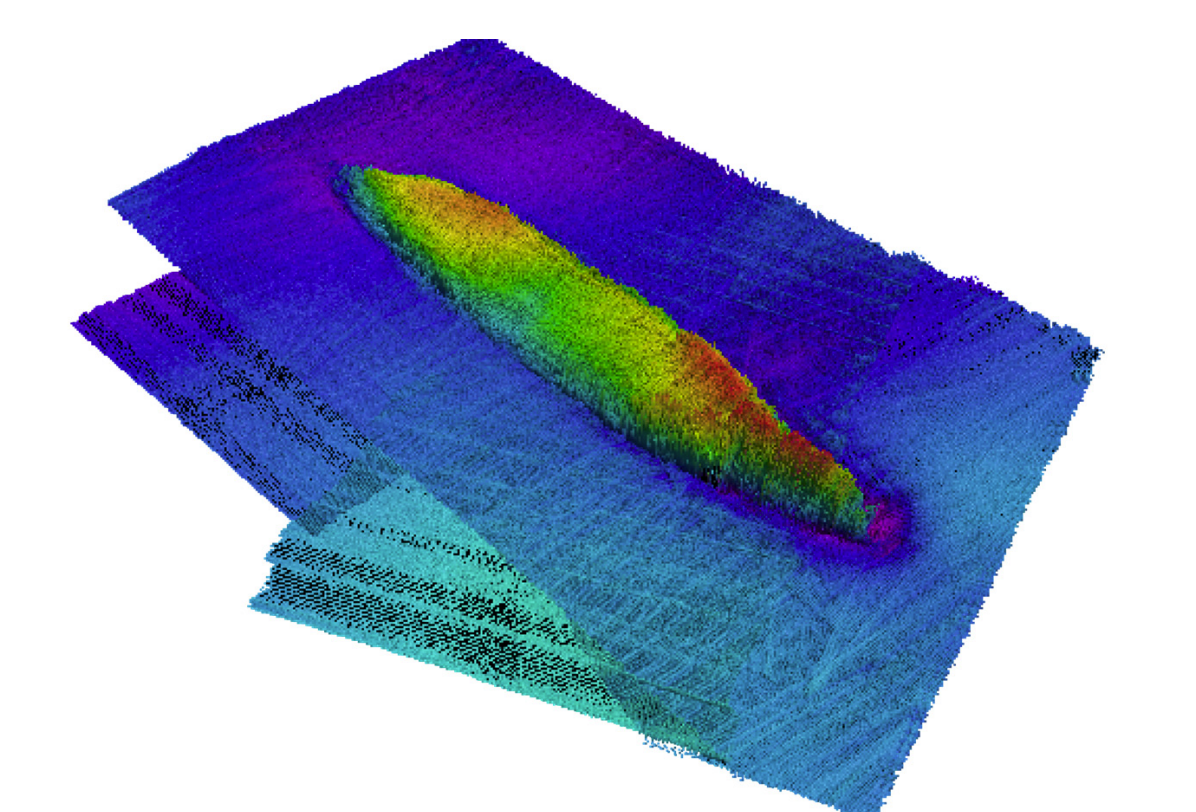

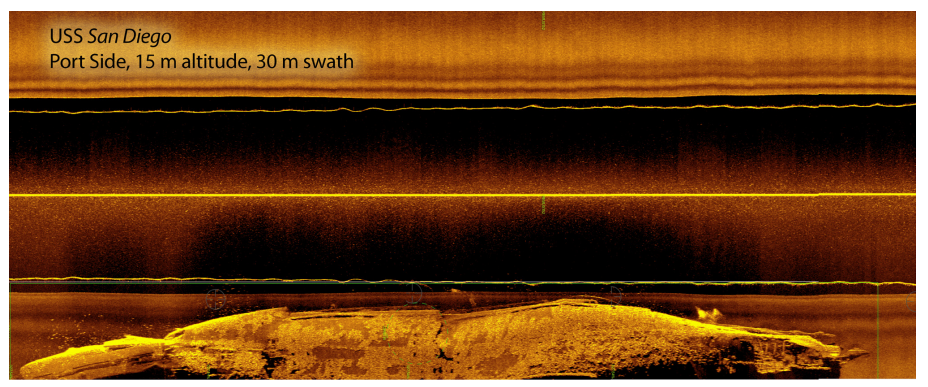

The results come from a series of four site visits and dive operations since 2016 conducted by a joint team of Navy historians, academics, researchers and divers with Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2 to get definitive answers about what happened to the cruiser. Advanced, hull-mounted sonar along with autonomous and remotely operated vehicles have helped the team develop detailed high-resolution maps of the San Diego’s wreckage site.

Diego the course of a 2017 survey. NHHC Image

The ship’s sinking, to the ocean floor 100 to 110 feet deep some six miles south of Long Island’s Fire Island, was the only major U.S. Navy warship sunk during the war. But the “abandon ship” order by Capt. Harley H. Christy, the ship’s commander, 15 minutes after the initial blast saved all but six men of San Diego‘s 1,183-man crew.

“The question of what sank San Diego has been one that’s been asked for several decades,” Alexis Catsambis, a maritime archaeologist with the Naval Historical and Heritage Command, said during a presentation live-streamed online.

A German U-boat, U-156, was known to have been in the area at the time on a mission to lay mines leading into New York Harbor, according to NHHC. The Navy had first reported its presence publicly a month earlier, on June 26, 1918, and a U-boat was spotted south of Nantucket, Mass., just two days before San Diego was hit.

“We believe U-156 sunk San Diego, and we believed it used a mine to do so,” Catsambis told the audience.

While U-boats also carried torpedoes, “there is no torpedo bubble trail reported by any of the lookouts,” added Ken Nahshon, a research engineer with the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Carderock Division.

The U-boats carried two types of mines, Nahshon said: Torpedo-tube launched and deck-deployed. A close study of the wreckage, computer modeling of water movement during an explosion and crew reports by crew members helped the team determine that

The 15,138-ton San Diego had arrived in New York City the day before, steaming in from Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, N.H., with the mission to escort ships across the Atlantic. The captain and crew were prepared for the known threats from German U-boats and ships before leaving Portsmouth. On that ill-fated morning, Christy posted 17 sailors as lookouts, “in case a submarine was spotted,” Catsambis said. The ship followed a course, zigging and zagging to avoid being easy prey for the U-boats. Watertight doors were closed.

But an explosion rocked the ship at 11:05 a.m. on a bright morning with clear skies. Despite turning toward the beach with engines at full steam, San Diego sunk into the sea 25 minutes later.

“The captain had done everything right at that point,” Catsambis said, noting, “they were prepared, but tragedy struck.”

“The response to that tragedy is admirable,” he added.

According to NHHC, German Kapitänleutnant Richard Feldt, U-156’s commander, had sent a wireless radio report on Sept. 6, 1918, claiming his crew had sunk San Diego and other ships. In a twist of irony, that same month U-156 met a similar fate when it was sunk by a mine in the North Atlantic. While its logs went down with it, Catsambis noted, it “is credited with the only attack on U.S. mainland,” in an attack against several vessels off Orleans, Mass., just two days after San Diego was sunk.

The Navy sent airplanes to the site almost immediately after San Diego sunk, and it dispatched salvage divers three times to ensure it wouldn’t become a hazard to navigation. “The dive team verified the site as that of San Diego, lying upside down and resting on its stacks, and revealed areas where the aerial bombs had been dropped on the wreck during the alleged sighting of a German submarine,” according to NHHC.

At the time, the U.S. fleet had little experience with underwater explosions, making the attack on San Diego critical to help understand, prepare and prevent for such events. “These men did everything right in preventing and in responding to a catastrophe off Long Island 100 years ago,” Catsambis said.

The recent dives and investigation have helped detail the mine’s impact on San Diego and how the ship reacted to the explosion. Its thick, armor belt around the hull helped keep San Diego intact, Nahshon said. While crushed at mid-hull section, San Diego remains relatively intact and contained, although its prominent four stacks collapsed and crushed as the cruiser listed and sunk.

The mine struck near the portside steam engine and a void space filled with coal. Water poured into empty spaces, causing the ship to quickly list and sink. Those empty spaces and openings made such coal-fired ships less survivable than oil-fired ships, said Art Trembanis, an associate professor of marine science and policy with the University of Delaware.

The wreckage “is teeming with fish,” Trembanis said, adding “it has become a 100-year-old artificial reef.”

operations as part of the 2017 MDSU training mission. NHHC Mission

But danger still lurks at the site. Unlike ships planned to become artificial reefs, San Diego sank full of hazards, from oils and lubricants to live, unexploded ordnance that ordinarily are stripped from ships before they are purposely sunk as ARs. The waters remain heavily navigated and popular for fishing. “There are implications for long-term management and exposure to folks, because it is a very diveable and achievable site,” Nahshon said. The findings will help the Navy manage the site, officials said.

Over the years, time, rough seas, storms and human interaction have taken a toll on the San Diego. Illegal salvage teams and divers had pilfered items including the ship’s propellers, ceramics, personal effects and even ammunition, according to the Navy. The site was placed on the National Register of Historic Place in 1998 and falls under the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004, which made it illegal to disturb sunken military ships and aircraft without a federal permit. Such wreckage sites remain Navy property and are considered the final resting place for crew members who died.

During the war, the ship, commissioned as the USS California in 1907 and renamed San Diego in 1914, had served as flagship for Rear Adm. William F. Fullam, the Patrol Force U.S. Pacific Fleet commander, according to NHHC. In July 1918, San Diego began a new assignment with the Atlantic Fleet to escort convoys crossing the submarine-infested waters of the North Atlantic. Christy, an 1891 U.S. Naval Academy graduate, continued to serve in the fleet and retired as a vice admiral in 1950, six months before his death.

In July, the joint Navy-private team placed a wreath over the wreckage site to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the sinking of San Diego. Just last month, a collection of 229 artifacts from the San Diego, including an M1892 bugle, padlock and a coffee cup, went on exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C.