The Marine Corps determined that a corroded propeller blade that came off mid-flight was the cause of the July 10, 2017, crash of a KC-130T transport plane.

That propeller did not go through proper maintenance the last time it was sent to an Air Force repair depot, which may have led to the damaged propeller remaining on the airplane that ultimately crashed and killed all 16 personnel onboard.

The Marine Corps released a partially redacted Judge Advocate General Manual Investigation today, which found that “the investigation found the primary cause of this mishap to be an in-flight departure of a propeller blade into the aircraft’s fuselage. … The investigation determined that the aircraft’s propeller did not receive proper depot-level maintenance during its last overhaul in in September 2011, which missed corrosion that may have contributed to the propeller blade liberating in-flight,” according to a Marine Corps press release on the investigation.

Marine Forces Reserve conducted the investigation and has made several recommendations for Naval Air Forces and for the Air Force to consider for their C-130 fleets.

The Crash

On July 10, 2017, a crew from reserve unit Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 452 (VMGR-452) departed their home station at Stewart Air National Guard Base in New York and flew to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, N.C. Their mission for the day was to transport six Marines and a Navy corpsman assigned to 2nd Marine Raider Battalion from North Carolina to Naval Air Facility El Centro, Calif., where the special operations unit was set to conduct pre-deployment training.

On July 10, 2017, a crew from reserve unit Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 452 (VMGR-452) departed their home station at Stewart Air National Guard Base in New York and flew to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, N.C. Their mission for the day was to transport six Marines and a Navy corpsman assigned to 2nd Marine Raider Battalion from North Carolina to Naval Air Facility El Centro, Calif., where the special operations unit was set to conduct pre-deployment training.

The aircraft departed Cherry Point at 2:07 p.m. Its last transmission to local air traffic control was at 3:46 p.m., and the last radar contact with the plane was at 3:49, when the plane was flying at 20,000 feet altitude, according to the JAGMAN.

The Marine Corps investigation found that Blade 4 on Propeller 2 (P2B4, in the report) became unattached, struck the port side of the fuselage, cut straight through the interior of the passenger area of the plane and became lodged in the interior of the starboard side of the plane. This damage kicked off a series of events that led to Propeller 3 colliding with the starboard side of the fuselage and ultimately the plane breaking into three pieces mid-air.

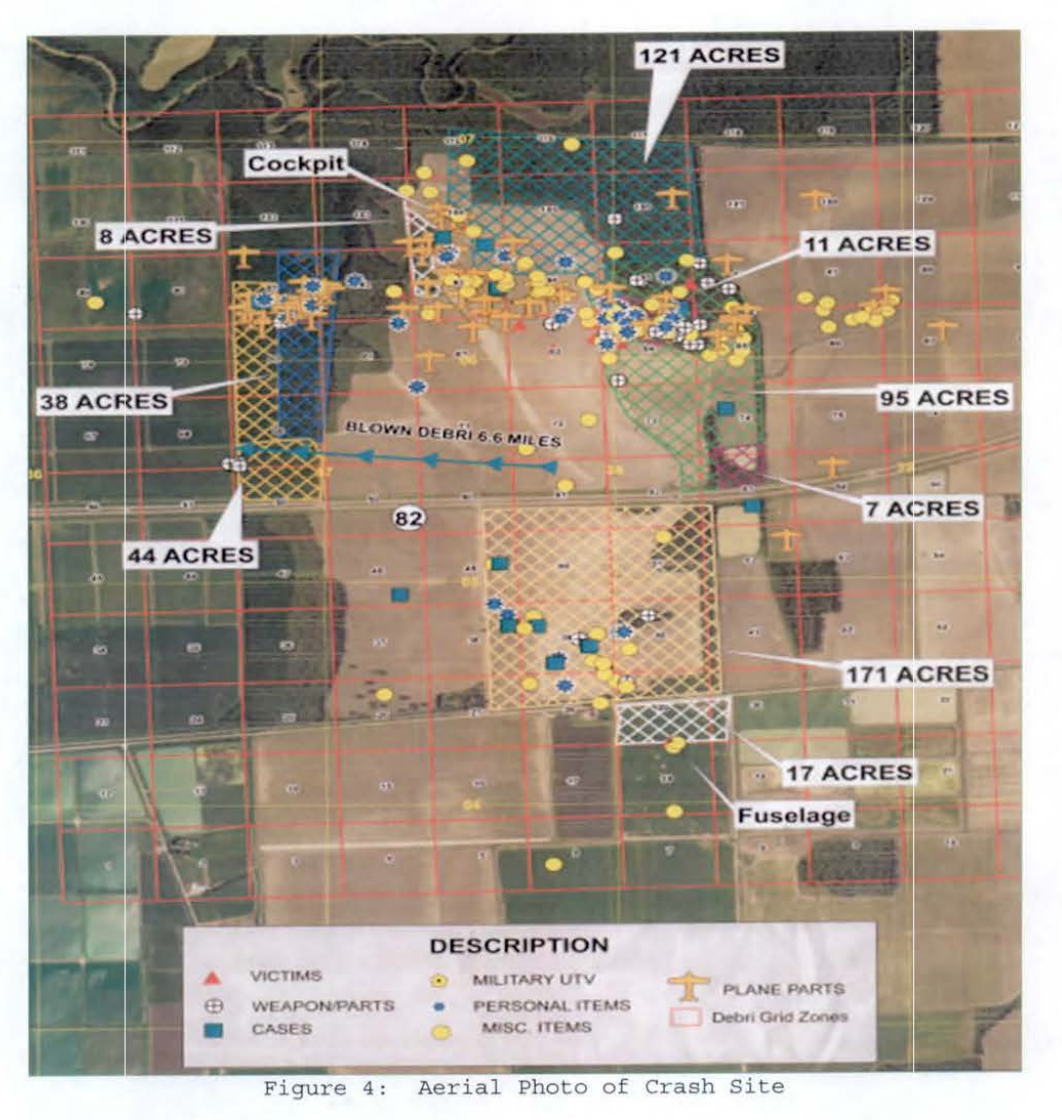

The cockpit and the rear of the fuselage crashed into two separate debris fields in a soybean field near Itta Bena, Miss. The middle section of the plane, where the passengers were located, further broke up in the air.

Marine Corps leadership made clear there was nothing the crew or passengers could have done to prevent the mishap or save themselves once the propeller blade broke loose.

Brig. Gen. Bradley James, commanding general of 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, which oversees the reserve KC-130T squadron, wrote in the investigation report that “the initial incident that started the cascading failure was the liberation of a blade from the #2 propeller assembly. The subsequent events quickly led to structural failure of the aircraft. Neither the aircrew nor anybody aboard the KC-130T could have prevented or altered the ultimate outcome after such a failure.”

Killed in the crash were: Maj. Caine Goyette, an active duty Marine who was flying the plane the day of the crash, who the report found was current on all his certifications and had 2,614 hours of flight time in military aircraft; Capt. Sean Elliott, an active duty Marine who co-piloted the plane and had 822 hours of military aircraft flight experience; Gunnery Sgt. Mark Hopkins, Gunnery Sgt. Brendan Johnson, Staff Sgt. Joshua Snowden, Sgt. Owen Lennon, Sgt. Julian Kevianne, Cpl. Collin Schaaff and Cpl. Daniel Baldassare, who were part of the VMGR-452 crew; and Staff Sgt. Robert Cox, Staff Sgt. William Kundrat, Sgt. Chad Jenson, Sgt. Talon Leach, Sgt. Joseph Murray, Sgt. Dietrich Schmieman and Petty Officer 2nd Class Ryan Lohrey, who were assigned to 2nd Marine Raider Battalion.

Maintenance Failures

Though no one on the plane could have stopped the events that unfolded, the maintenance community could have prevented them. The investigation found a failure to inspect the propeller during its last depot maintenance period, as well as missed opportunities during squadron-level maintenance to potentially notice the corroded blade.

The plane itself was 24 years old and was last in depot maintenance at Warner-Robins Air Logistics Center (WR-ALC) in Georgia in August 2011 for blade overhauls. The Air Force complex is manned by civilian employees who rework and overhaul propellers and is the sole source of this overhaul work for Navy and Marine Corps C-130s.

According to the JAGMAN, the Navy and Marine Corps require C-130 propellers to undergo an overhaul every 5,000 to 6,000 flight hours. Investigators studying the plane wreckage found not only corrosion in the Blade 4 Propeller 2, but found anodize coating inside the corrosion pitting – which means the corrosion was there during the 2011 overhaul, and instead of removing the corrosion and fixing the blade, the coating was applied over the damaged blade.

“Negligent practices, poor procedural compliance, lack of adherence to publications, an ineffective [quality control/quality assurance] program at the WR-ALC, and insufficient oversight by the [U.S. Navy], resulted in deficient blades being released to the fleet for use on Navy and Marine Corps aircraft from before 2011 up until the recent blade overhaul suspension at WR-ALC occurring on 2 September 2017,” reads the JAGMAN, referring to the September “Redstripe” standdown of all Navy C-130s until further blade inspections could be conducted.

Twelve of the 16 total blades on the plane that crashed – four blades on each of four propellers – “were determined to have corrosion that existed at the time of their last overhaul at WR-ALC, proving that over the course of the number of years referred to above, that WR-ALC failed to detect, remove and repair corrosion infected blades they purported to have overhauled. … Thirteen of the sixteen blades on the [mishap aircraft] had other discrepancies proving that, over the same span of years referred to above, WR-ALC was deficient in the effective application of the following steps: anodization, epoxy primer and permatreat,” the JAGMAN continues.

Though less severe than the failure at the Air Force depot, the report noted concerns with maintenance practices within the squadron earlier in 2017, in the months before the crash.

According to the JAGMAN, the squadron failed to establish a formal process to track and perform the 56-day conditional manual inspections of the propeller blades that can be triggered when the plane is not used or when the blades are not rotated for 56 days. Due to a lack of a clear procedure, on at least two occasions in 2017 a conditional inspection was triggered, but the squadron believed that separate inspections met the requirement and therefore the maintainers did not do the manual blade inspection. However, the investigation notes that it could not be determined whether a manual inspection could have identified the damage to the blade that led to it becoming detached mid-flight and causing the crash.

Recommendations

In August 2017, a Navy engineering team conducted a process audit at Warner-Robins Air Logistics Complex and found that, even though the Navy and Marine Corps have separate blade overhaul procedures and standards from the Air Force, the civilian workforce had failed to track which blades belonged to which service and therefore which maintenance standards to apply. Only about 5 percent of the blades belong to Navy and Marine Corps planes, but the Navy recommended creating a standard work flow process and the Air Force agreed to adopt all the Navy’s processes.

The report also recommends that Warner-Robins Air Logistics Complex maintain electronic records of all blade overhauls that can be kept permanently, compared to the paper records that are discarded after two years. It also recommends greater Navy oversight of Navy/Marine Corps overhauls at Warner-Robins, blade overhauls at a more frequent interval than 5,000 hours, and additional clarity on the 56-day inspections.