A year has passed since the last communication was received from Argentinian submarine ARA San Juan (S-42), but the search for the missing boat continues with the help of a Texas-based undersea mapping firm.

Starting in early October, Houston-based Ocean Infinity deployed its research vessel Seabed Constructor and an array of five autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) to comb the South Atlantic off the Argentine coast for the missing attack boat and its crew of 44 sailors now presumed dead.

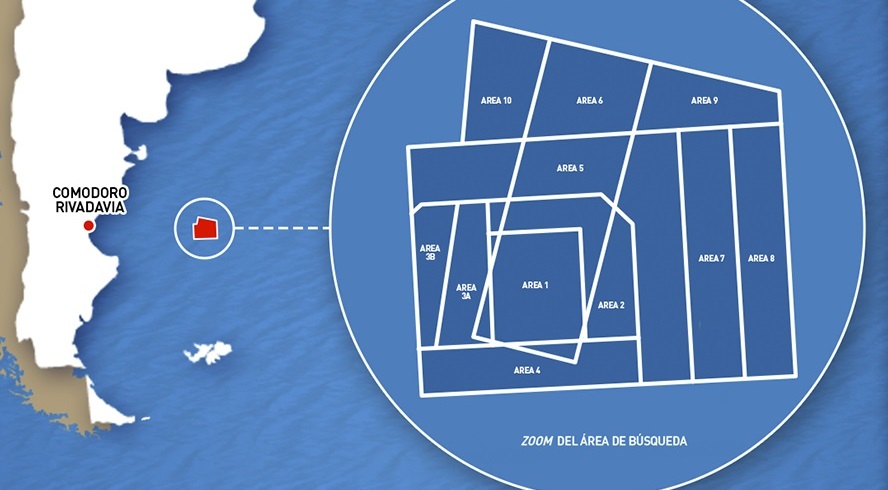

The firm had several clues to start with, such as San Juan’s location, roughly 240 nautical miles east of Argentina’s San Jorge Gulf, when the sub sent its final communication.

“We know the weather at the time was terrible. We know the current was heading north. The wind was blowing from the southwest,” Oliver Plunkett, chief executive of Ocean Infinity, told USNI News. “On the surface, the submarine was in great difficulty.”

However, what happened after the submarine slipped beneath the surface for the final time remains a mystery, occurring in what Plunkett describes as a challenging but fascinating undersea environment.

“It’s fascinating: largely the seabed is flat. But it’s a bit like saying largely the United States is flat, except for when you get to the Rocky Mountains,” Plunkett said. “Some parts of the seabed are like the Rocky Mountains.”

Using Plunkett’s analogy, San Juan could be in the undersea equivalent of where the Great Plains meet the Rockies – either in relatively shallow and flat seabed or deep below the surface, where the floor is pocked full of canyons and mountains.

Previous search efforts yielded no clues of San Juan’s final resting place – just undersea imagery of rock formation and a few long-lost fishing vessels. The U.S. Navy had sent rescue teams to assist in the search when there was still hope of finding the crew alive. A U.S. Navy Cable-operated Unmanned Recovery Vehicle (CURV) 21 and a Navy-funded research vessel were later sent to search for San Juan’s wreckage.

Ocean Infinity did not release the terms of their contract with the Argentine government, other than the search term was for 60 days with an option to continue for an additional 60 days. The first two-month search period just ended. Plunkett plans to review the data collected so far, recalculate where to look, and resume the search in February.

According to Argentinian media accounts, the government will pay Ocean Infinity a $7.5-million bonus if San Juan is found, as reported by the Buenos Aires Times.

The Final Moments of San Juan

Searchers know that just after midnight on November 15, 2017, San Juan’s captain alerted his Argentine Navy superiors via a satellite phone call that salt water had poured into the sub through its snorkel, which is used to bring fresh air to the sub when submerged.

“Seawater leaked in through the ventilation system into battery system No. 3, causing a short circuit and the early stages of a fire where the batteries were. The batteries on the external bow are out of service. We are currently submerging with a divided circuit. Nothing new to report regarding personnel. Will keep you informed,” according to a CNN English translation of the message, which was broadcast by Argentinian channel A24.

At 6 a.m. the captain sent a typed message repeating his satellite phone message, per Argentine Navy procedure. At 7:30 a.m. the sub sent a message stating it was proceeding on course. That was the final message received.

At 10:31 a.m., an undersea explosion was registered by an anti-nuclear proliferation listening station. U.S. and international experts determined the explosion was not nuclear but occurred in roughly the same area San Juan was believed to be operating at this time, according to the Argentine Navy.

“The nuclear listening station recorded a seismic event, and that’s a very key piece of evidence,” Plunkett said. “But there’s a degree of error in location.”

The problem for searchers, Plunkett said, is that the explosion, the final communication and the sub’s course are all estimates; best guesses, Plunkett said. A variation of just a few degrees in estimated coordinates could be the difference of searching in relatively shallow waters of up to 900 feet deep or off the continental shelf’s sheer drop-off down to depths of more than a mile.

“That’s on the western side of our search area, running north-south,” Plunkett said. “In the lower area, there are some quite long and deep canyons. The deepest canyon was 400 meters (1,312 feet) deep and 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) across. We have to think very carefully about mission planning to make sure we have sufficient coverage through the canyons.”

AUVs

Ocean Infinity deploys five AUVs at a time to constantly send sound waves to the floor. The AUVs operate in search grids, in a process Plunkett likens to mowing a lawn – passing in straight lines, back and forth, in a designated search box. The AUVs can operate for 60 hours before surfacing to recharge batteries and download their data aboard the mothership, Seabed Constructor.

The main benefit of using AUVs, compared to using cable-tethered underwater vehicles, Plunkett said, is the surface weather doesn’t affect their operations, other than scheduling deployment and recoveries. The vehicles operate close to 200 feet from the ocean’s bottom, bouncing sound waves off the seabed.

The AUVs can correct their courses if, for instance, they come up to an undersea mountain, Plunkett said. The AUV can stop moving forward, loop around or climb above the obstacle and carry on its mission without being programmed to do so.

The motors on Ocean Infinity’s AUVs are very quiet, and the vehicles are shaped like mini-submarines to make their travel through water as efficient as possible and with as little drag as possible, Plunkett said. The design enhances the sensors’ ability to work.

“A lot of the sensors, the sonar, echo sounds, rely on sound. That smooth glide is really important to collecting the data. What the sensor does is fire out a sound wave, it then hears the return, and it’s the assessment of the time and strength of that return that is converted into an image of the seabed,” Plunkett said. “Anything that interferes with the quality of the sound wave – either noise from the AUV, or vibration, or other distortions – really damages the quality of data.”

Until now, much of the search for San Juan had relied on traditional sensors on surface ships or from underwater vehicles tethered by cables to mother ships. While the Navy’s CURV-21 can dive to 20,000 feet, any movement or vibrations from the cable connecting it to the surface ship can distort the quality of ocean floor images.

Greater Undersea Understanding

So far, Ocean Infinity has not had luck finding San Juan. However, an exciting byproduct of the firm’s search is a greater understanding of what is below the sea surface in this part of the Atlantic.

“There’s some quite interesting sea life and geographical features. It’s extraordinary how many submarine-shaped and -sized rocks are down there,” Plunkett said. “There’ve been a number of times the guys on the ship got excited because there’s something 40 meters long, 5 meters wide, 6 meters high, and it’s turned out to be wrong. It’s truly astonishing.”

Such lessons learned from searching for San Juan, and from Ocean Infinity’s previous mission searching for downed Malaysian Airlines flight MH370, have caught the attention of U.S. Navy officials. The firm signed a cooperative research development agreement with the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command.

The five-year partnership will focus on expanding capabilities and improving technology for deep-sea data collecting. William Burnett, the command’s deputy commander and technical director, cited Ocean Infinity’s technology as a model for the Navy to follow when discussing his team’s work charting ocean temperature at the recent Naval Submarine League annual symposium.

“Just the technology and the ability, and what they’re learning from operating that vehicle, I want to learn that as well and quickly get that into naval oceanography and also the U.S. Navy as well,” Burnett said.

Around the globe, very little is known about of what’s below the ocean’s surface, Plunkett said. If the world’s seafloors were divided by one-kilometer squares, he said, only 3 percent would have usable data. More than half the squares would be completely unexplored.

“There are more complete maps of Mars and the moon than there are of the seabed,” Plunkett said. “It’s extraordinary; we know so little about the deep oceans.”