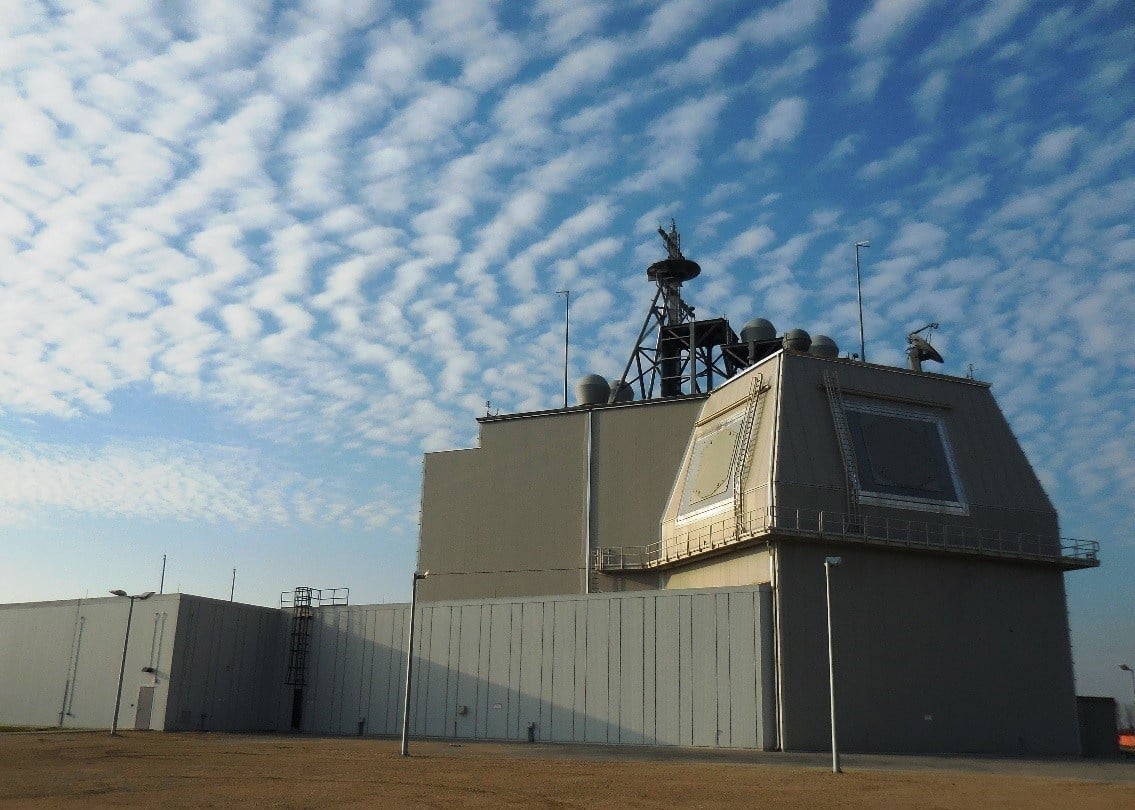

Converting Aegis Ashore facilities in Poland and Romania into land stations for cruise missile coupled with already available sea-based and air-launched missiles would complicate Kremlin planning on how to defend itself from attack or strike targets in Europe, a former U.S. defense official on Wednesday.

In a telephone conference call with reporters, Abraham Denmark, director of the Asia program at the Wilson Center and a former Pentagon official, said the two facilities “could fairly readily be turned” from defensive posture against Iranian ballistic missiles threatening Europe to an offensive capability targeting Russia. This would be a “direct threat” contention the Kremlin has said violated the existing treaty and was the American goal from that start in deploying the missiles, radars and fire control systems so close to its borders.

With the United States’ announced plans to withdraw from the 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces treaty between Washington and Moscow and not having such a land-based missile in its inventory, conversion indeed might be an option in American military planning.

In setting the stage for the discussion and question-and-answer session, Robert Litwak, senior vice president at the Wilson Center, said American administrations since 2014 have publicly called out Russia for its development and deployment of a new set of mobile intermediate range cruise missiles as violating the treaty.

Russia, in response, kept pointing to Aegis Ashore, American and NATO armed drones and the dummy missiles used in targeting exercises as INF treaty violations.

The treaty, one part of a series of arms control agreements, reached during the Cold War did not cover all kinds of intermediate-range missiles.

“INF meant nothing for ships at sea” or missiles launched from aircraft, Matthew Rojansky, director of the center’s Kennan Institute, said. These were among the United States’ strongest military capabilities in deterring Soviet aggression in Europe.

Looking at the strategic situation in Europe now, the Aegis Ashore site in Romania was declared fully operational in 2016. Construction problems, however, have slowed the work in Poland and it will not be operational until 2020, a Senate Armed Services subcommittee was told earlier this year.

In the Pacific, Japan has announced the awarding of contracts for its first Aegis Ashore systems that are expected to become operational in 2023.

“The U.S. does not have capabilities [for a mobile land-based intermediate range missile] on hand” now or in the immediate future to counter Russia, China or any other power, Litwak said.

NATO allies, as well as Japan, have expressed concerns about the United States’ walking away from the treaty and likely would not be receptive to stationing new American intermediate-range missiles on their soil. This runs counter to the Cold War experience.

American plans to deploy Pershing II missiles with atomic warheads along the Iron Curtain to meet growing Soviet missile threats in Europe were marked by large protests, but the governments in the NATO countries stayed firm. Ultimately, the missiles were deployed.

Litwak said Europeans see the treaty today “as a pillar of European security architecture.” The treaty only involves the United States and Russia. Other nuclear powers, such as China, France, the United Kingdom, India and Pakistan, are not involved; and neither are Iran, North Korea and Israel.

The Trump administration, on the other hand, weighs the treaty “as a constraint on our sovereignty” rather than serving the national interest, he said. Rojansky added some in the administration could also see the move “as a way of exhausting the Russians through another arms race,” in effect “doubling down” on the Kremlin’s opening gambit of deploying its missiles and forcing it to up its defense spending in a time of negative or flat gross domestic product.

Looking to the Pacific, where China has an operational nuclear triad coupled with an intermediate range missile inventory, Denmark said Japan is very concerned about the American willingness to defend Tokyo in any showdown over its territorial disputes with Beijing and possibly from North Korea.

Noting Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s most recent visit to Beijing and the pomp, circumstance and military show surrounding it, he added, “Japan has been hedging” in light of Trump’s “criticism of alliances generally and Japan particularly,” he said.

While Europe is about land power the geography of Asia puts the emphasis on naval assets, Denmark said. China has made “significant investments that would violate the INF treaty” if it were a signatory and likely would keep it from joining any new agreement, he said.

Beijing’s development of its intermediate range missiles could reach not only American bases in Japan, but also Guam. Other potential targets could include Taiwan and India. “They’re all in on intermediate-range missiles” as a deterrent and a show of military strength.

But if converting Aegis Ashore would complicate Kremlin military planning so would deployment of U.S. mobile intermediate-range missiles to Alaska and Guam muddle Beijing’s, but here again there is no existing American system ready to deploy.

He conceded mobile land-based systems like those in China and Russia are “more efficient and can move about” more freely than an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer that costs almost $2 billion and carrying a limited number of Tomahawk cruise missiles.

“U.S. allies [Japan, the Philippines, Australia] are not terribly excited” about the U.S. decision to leave the treaty or the prospect of hosting American missiles aimed at China.

Rojansky said the move does throw into question whether Moscow and Washington will be able to update its strategic arms agreement in 2021.

There has been no serious proposal from Russia on either the strategic arms or INF treaty, Rojansky said. “It’s all or nothing” from nuclear weapons, to missiles, to cyber, space and conventional weapons. Likewise, on Capitol Hill, where Congress would have to ratify any new treaties, there is a “we do not trust the Russians” sentiment on any of these issues.

The reasons given are continued interference in American elections, active military support of Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian civil war and ongoing financial and arms support of Ukrainian separatists.