Halfway through his midwatch, 19-year-old Seaman Daryl Weathers scanned the screens in the darkened radio shack as the USS Abner Read (DD-526) hunted Japanese submarines off the Aleutian island of Kiska on Aug. 18, 1943.

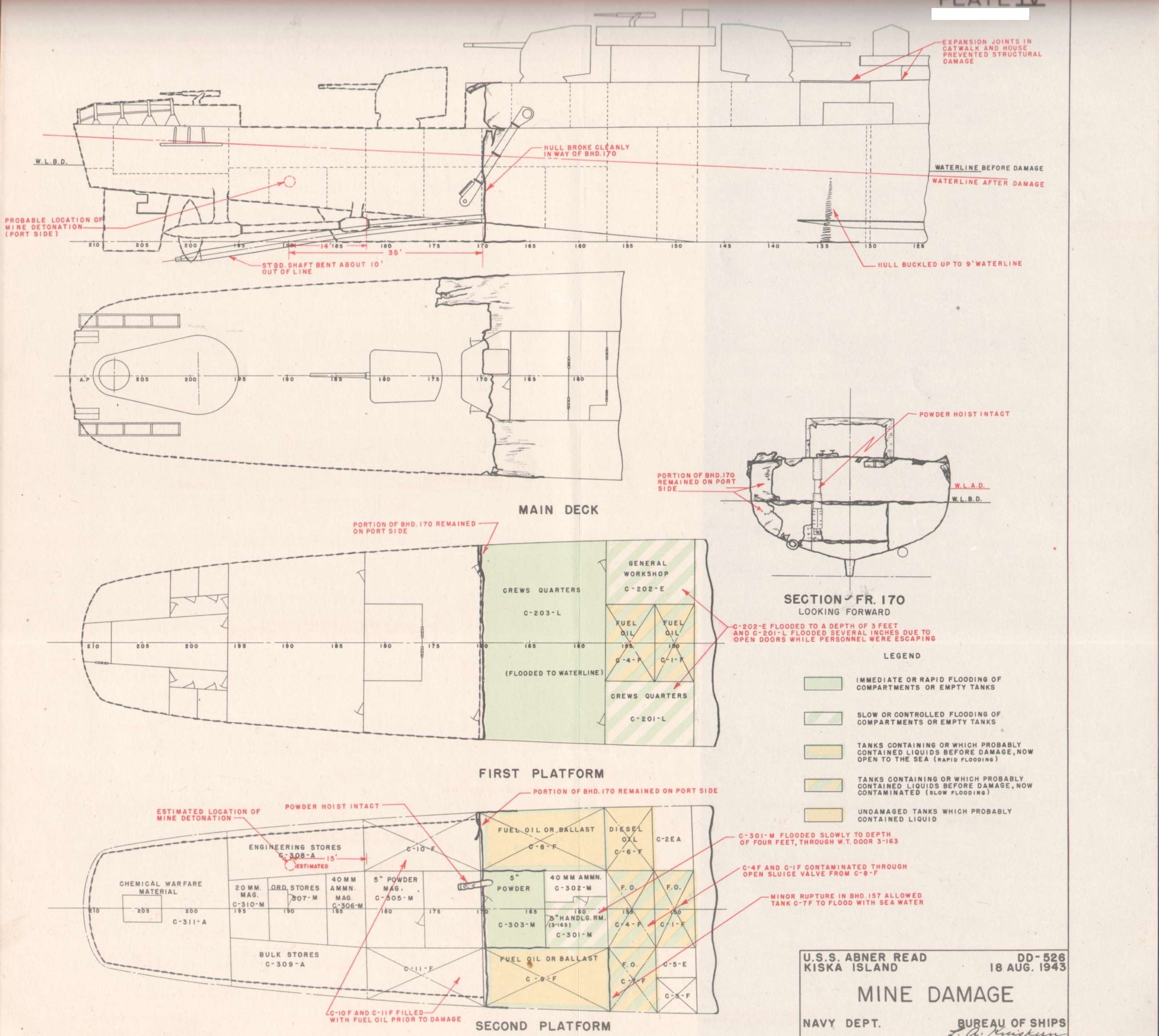

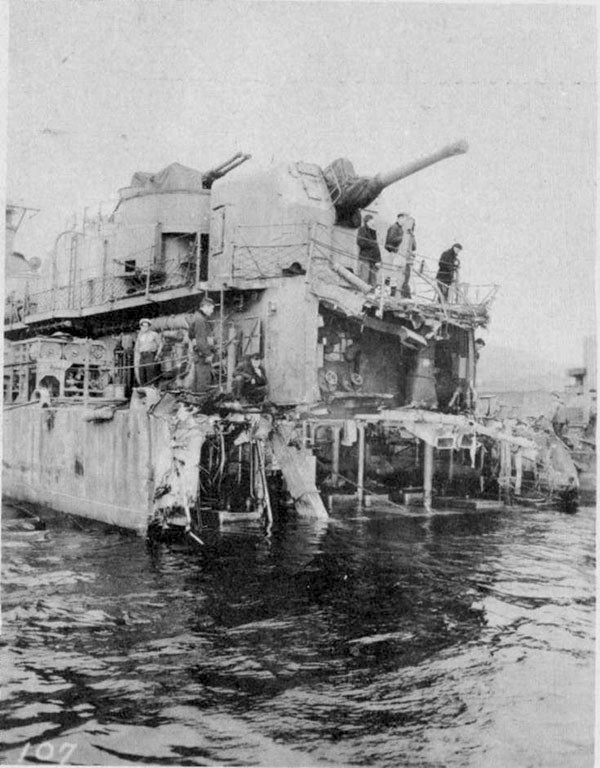

At 1:50 a.m., an explosion rattled the Fletcher-class destroyer, bending the shafts and buckling interior spaces. Blast pressure even straightened aluminum bunk hooks, wounding and trapping some men as they slept. Unbeknownst to the crew, a floating Japanese mine had detonated portside aft of midship as the ship made a full right rudder turn, nearly slicing off the stern at frame 170.

Weathers rushed through choking, blinding chemical smoke to join frantic rescue efforts at the stern, which just two minutes later would tear away in the oil-slicked waters. “There’s three sleeping compartments back there,” Weathers, now 94 and living in Seal Beach, Calif., told USNI News. Sailors used a net to grab a dying man before the sea swallowed the stern, taking 70 men with it into dark, frigid waters nearly 300 feet deep.

The remaining crew scrambled to steer Abner Read, now adrift, away from the approaching rocky coast. Days later, the destroyer was towed to nearby Adak and then Dutch Harbor before the long tow to Puget Sound, Wash., for permanent repairs and a new stern. By December 1943, it resumed service, training crews off California before joining the fleet in Leyte Gulf in 1944. A Japanese kamikaze airplane struck the destroyer on Nov. 1, 1944, triggering explosions that sunk the ship and killed 22 crew.

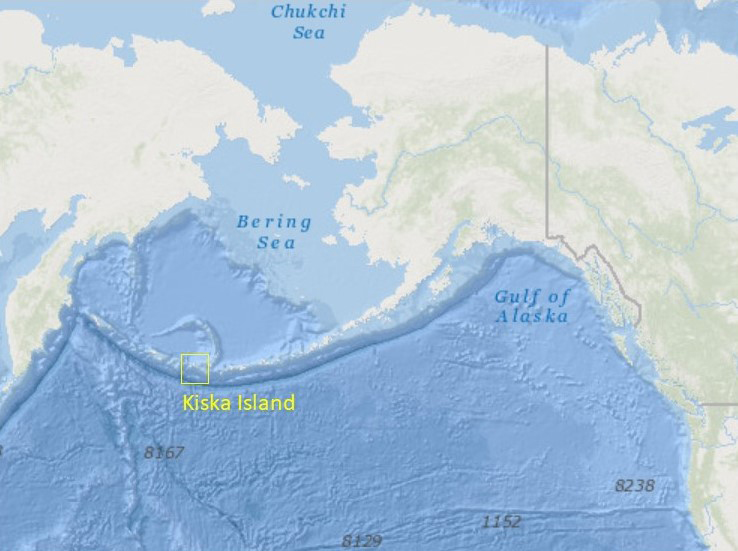

For 75 years, Abner Read’s and the 70 men who perished with it remained undiscovered – a lesser-known part of history as much as the 1943 Aleutian campaign that dispatched Abner Read to the rugged, remote Alaska archipelago. The destroyer joined a broader naval and military effort to dislodge Japanese imperial forces that a year earlier had invaded and occupied the islands of Kiska and Attu during the attack on Midway. That occupation was the first and only time that foreign forces have occupied and controlled any U.S. territory in 200 years.

But on July 17, a team of researchers and scientists searching four areas around Kiska to document the underwater battle that took place in the waters located Abner Read‘s 75-foot stern section in 290 feet of water, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration officials announced Wednesday. “This is a significant discovery that will shed light on this little-known episode in our history,” retired Rear Adm. Tim Gallaudet, acting undersecretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere and acting NOAA administrator, said in the news release. “It’s important to honor these U.S. Navy sailors who made the ultimate sacrifice for our nation.”

Encrusted with marine life, Abner Read’s stern rests nestled in the sandy bottom, upright but listing 4 degrees. “She’s intact,” said Andrew Pietruszka, an underwater archaeologist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California-San Diego. “I didn’t really see any evidence of explosion.”

More importantly, the discovery formalizes the underwater graves for the 70 men who went down with the stern. “We thought we could still find their final resting place and we could still honor them,” said Pietruszka, one of three principal investigators in the Kiska search. The discovery came on the fifth day of a search off Kiska enabled by a break in the weather, which in the region is notoriously unpredictable with often thick fog, winds and choppy seas. “The weather is extremely poor and temperamental,” he said.

The 15-member team with Project Recover, a private-public partnership, relied on multi-beam sonar and other advanced underwater technology, along with some high-speed remotely operated vehicles, to reach and search the area. The team closely watched the high-resolution live video feed across their screens from the research ship Norseman II, and it wasn’t long before they saw what appeared to be the stern. “The shape and size matched exactly what it should be,” he said. “The depth charge rack was very discernible,” and the five-inch gun, Turret No. 5, “it’s still there.”

For Robert Cressman, a historian with the Naval History and Heritage Command, the stern’s discovery and the continuing research and ongoing analyses from the Kiska project is shedding new light and providing new, and little known, details about the wartime experiences, roles and contributions of the Abner Read and other naval vessels that took part in the lesser-known, 15-month Aleutians campaign. “It’s a very inhospitable theater,” he said.

Cressman, who edits the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, said when he heard about NOAA’s planned Kiska search, “I found there was significant gaps in the history.” So he’s devouring the latest discovery details and pouring through historical records and documents, including muster rolls, deck logs and commander biographies.

“We’ve always known generally where the wreckage was,” he noted. Its remote location may help preserve and safeguard it, along with federal law that protects the site since “it is considered a war grave.”

The destroyer arrived in the Aleutians in mid-May 1943 and provided shore bombardment and other advance fire for the arrival of U.S. troops. Japan, however, had “managed to evacuate the entire garrison, and we didn’t know about it,” he said. Except for three dogs U.S. soldiers found no one on Kiska.

Abner Read, commissioned just six months before the mine blast, “had such a fascinating but brief career,” Cressman said, noting the destroyer’s four battle stars and other citations awarded for service that included battles in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea. “She was a very well-run ship,” he added. “Her final battle was just an incredible tale.”

Weathers, for one, always knew where the stern and his fallen crewmen rested and figured it posed no hazard. He knew little of where he and the destroyer headed when the Abner Readsteamed from San Francisco that spring to the Aleutians. They rode the ship as it was towed – through fits of poor weather and seas – back to Puget Sound for repairs. During training missions, he married his sweetheart, Alice, and one day took off again on a mission to the South Pacific, first to New Guinea and then to Leyte.

In Leyte, Abner Read came under heavy bombardment as aircraft zipped above and anti-aircraft rounds peppered the sky. Weathers manned a 40mm anti-aircraft gun on the starboard side when he spotted a suicidal Japanese bomber aiming for the ship. Bombs fell on the ship and the plane struck the deck as fireballs exploded. “Ultimately the gasoline and the fire went down and blew up a magazine in the bottom of the ship,” he recalled. The rest of [the ship] is still down there off Leyte Gulf.”

Weathers was “banged up pretty bad” and ultimately evacuated. “Fortunately, I didn’t die,” he said, matter of factly. As far as he knows, he may be one of perhaps two remaining survivors. “None of them were good,” he said of memories of his wartime service. “The good part was I survived.”

He left the Navy as a third-class petty officer and settled in his hometown of Los Angeles, where he raised several children and worked as a truck driver and became a businessman and occasionally played trombone, tuba and string bass for several bands. His wife of 74 years passed away in January. “We had a good life. Of course, I was gone a lot,” he said. “I tell you, when your time is up, it’s up, and I don’t worry about everything in between.”